|

African armyworm (Spodoptera exempta) It is usually an occasional pest, but when outbreaks occur damage to millet can be devastating. The caterpillars eat the above-ground parts of the plants leaving only the base of the stem. |

|

|

What to do:

|

|

Stemborers: African maize stalkborer (Busseola fusca) Stemborers are the most important insect pests of maize in sub-Saharan Africa. Yield losses vary between 10-70%. Several species have been reported. The importance of a species varies between regions, within a country or even the same eco-region of neighbouring countries. At least four species attack maize in eastern and southern Africa, with yield losses reported to vary from 20 to 40%, depending on agroecological conditions, crop cultivars, agronomic practices and intensity of infestation.

The most important are the African maize stalkborer (Busseola fusca) and the spotted stemborer (Chilo partellus) (see also below).

The pink stalkborer (Sesamia calamistis) and the sugarcane stalkborer (Eldana saccharina) are of minor importance in maize.

Early warning signs: Young plants have pinholes in straight lines across the newest leaves. This is the time to treat - before the caterpillars move into the stem. |

|

|

What to do:

|

|

Blast (Pyricularia grisea) Lesions on foliage are elliptical or diamond-shaped, approximately 3 x 2 mm. Lesion centres are grey and water-soaked when fresh but turn brown upon drying. Lesions are often surrounded by a chlorotic halo, which will turn necrotic giving the appearance of concentric rings. The disease is favoured by hot, humid conditions.

|

|

|

What to do:

|

|

Crazy top downy mildew (Sclerospora graminicola) Symptoms often vary as a result of systemic infection. Leaf symptoms begin as chlorosis at the base and successively higher leaves show progressively greater chlorosis. On the lower leaf surface of infected leaves greyish white fungal growth may be observed. Severely infected plants are generally stunted and do not produce panicles. Green ear symptoms result from transformation of floral parts into leafy structures. The disease is prevalent during rainy seasons.

|

|

|

What to do:

|

|

Ergot (Claviceps spp.) Cream to pink sticky "honeydew" droplets ooze out of infected florets on panicles. Within 10 to 15 days, the droplets dry and harden, and dark brown to black sclerotia (fungal fruiting bodies) develop in place of seeds on the panicle. Sclerotia are larger than seed and irregularly shaped, and generally get mixed with the grain during threshing. Conditions favouring the disease are relative humidity greater than 80%, and temperatures between 20 to 30 degC. The sclerotia falling on the soil or planted with the seed germinate when the plants are flowering. They produce spores that are wind-borne to the flowers, where they invade the young kernels and replace the kernels with fungal growth. The fungal growth bears millions of tiny spores in a sticky, sweet, honeydew mass. These spores are carried by insects or splashed by rain to infect other kernels.

|

|

|

What to do:

|

|

Grasshoppers Several species of grasshoppers attack millets. Short-horned grasshoppers include Zonocerus spp, Oedaleus senegalensis, Kraussaria angulifera, Hieroglyphus daganensis, Diabolocantatops axillaris among others. The long horned edible grasshopper (Homorocoryphus niditulus) is a pest in East Africa. Grasshoppers defoliate and eat the panicles. They are not of economic importance when present in low numbers. However, invasion by a swarm of grasshoppers may result in serious grain losses.

|

|

|

What to do:

|

|

Long smut (Tolyposporium penicillariae) Immature, green fungal bodies (sori) larger than the seed develop on panicles during grain fill. A single fungal body (sorus) develops per floret. As grain matures, sori change in colour from green to dark brown. Sori are filled with dark spores. Infection takes place at temperature range of between 21 and 31°C, and at relative humidity greater than 80%. The disease is spread by wind-borne spores and rain.

|

|

|

What to do:

|

|

Mealybugs Mealybugs are small, flat, soft bodied insects covered with a distinctive segmentation. Their body is covered with a white woolly secretion. They suck sap from tender leaves, petioles and fruits. Seriously attacked leaves turn yellow and eventually dry. This can lead to shedding of leaves, inflorescences, and young fruit. Mealybugs excrete honeydew on which sooty mould developed. Heavy coating with honeydew blackens the leaves, branches and fruit. This reduces photosynthesis, can cause leaf drop and affect the market value of the fruit.

A wide range of natural enemies attacks mealybugs. The most important are ladybird beetles, hover flies, lacewings, and parasitic wasps. These natural enemies usually control mealybugs. However, mealybugs can cause economic damage to mango when natural enemies are disturbed (for instance by ants feeding on honeydew produced by mealybugs or other insects) or killed by broad-spectrum pesticides, or when mealybugs are introduced to new areas, where there are no efficient natural enemies.

The latter is the case of two serious mealybug pests on mangoes in Africa: Rastrococcus invadens in West and Central Africa and Rastrococcus iceryoides in East Africa. These mealybugs, of Asian origin, were introduced into Africa, where they developed into serious pests since the natural enemies present were not able to control them. They cause shedding of leaves, inflorescences and young fruits. In addition, sooty moulds growing on honeydews excreted by the insects render the fruits unmarketable and the trees unsuitable for shading. They cause direct damage to fruits leading to 40 to 80% losses depending on locality, variety and season. Rastrococcus invadens was brought under control in West and Central Africa by two parasitic wasps (Gyranusoidea tebygi and Anagyrus mangicola) introduced from India (Neuenschwander, 2003).

Rastrococcus iceryoides is a major pest of mango in East Africa, mainly Tanzania and coastal Kenya. Although several natural enemies are known to attack this mealybug in its aboriginal home of southern Asia (Tandon and Lal, 1978; CABI, 2000), none have been introduced so far into Africa (ICIPE). Insecticides do not generally provide adequate control of mealybugs owing to their wax coating. |

|

|

What to do:

|

|

Millet head miner (Heliocheilus albipunctella) It is the most important insect pest of pearl millet in the Sahel. Moths deposit their eggs on the heads of millet, preferring half-emerged and fully-emerged flowering heads. The caterpillars mine into the seeds of the millet head, damaging the millet panicle (i.e. the flower head, where the grain is formed). It has been reported to cause complete crop loss. Pupation takes place in the soil.

|

|

|

What to do:

|

|

Shoot fly (Atherigona soccata) Sorghum shoot fly, (Atherigona soccata), is a particularly nasty pest of sorghum in Asia, Africa, and the Mediterranean area. Females lay single cigar-shaped eggs on the undersides of leaves at the 1- to 7-leaf stage. The eggs hatch after only a day or two of incubation, and the larvae cut the growing point of the leaf, resulting in wilting and drying. These leaves, known as 'deadhearts', are easily plucked. When a "dead heart" is plucked, it releases an obnoxious odor. Adult resemble small houseflies. They are about 0.5 cm long. The shoot fly has been reported as attacking pearl millet. Damage occurs 1-4 weeks after seedling emergence. The damaged plants produce side tillers, which may also be attacked. The shoot fly's entire life cycle is completed in 17-21 days. Infestations are especially high when sorghum planting is staggered due to erratic rainfall. Temperatures above 35°C and below 18°C reduce shoot fly survival, as does continuous rainfall. |

|

|

What to do:

|

|

Stemborers Several species of stemborers attack millet including the millet stemborer (Coniesta ignefusalis), the maize stalkborer (Busseola fusca), the spotted stalkborer (Chilo partellus), and the pink stalkborer (Sesamia calamitis). Stemborer caterpillars bore into stems of millets disrupting the flow of nutrient from the roots to the upper parts of plants. Attack on young millet plants causes damage known as "dead hearts". In older plants the top part of the stem dies as a result of tunnelling by the borers.

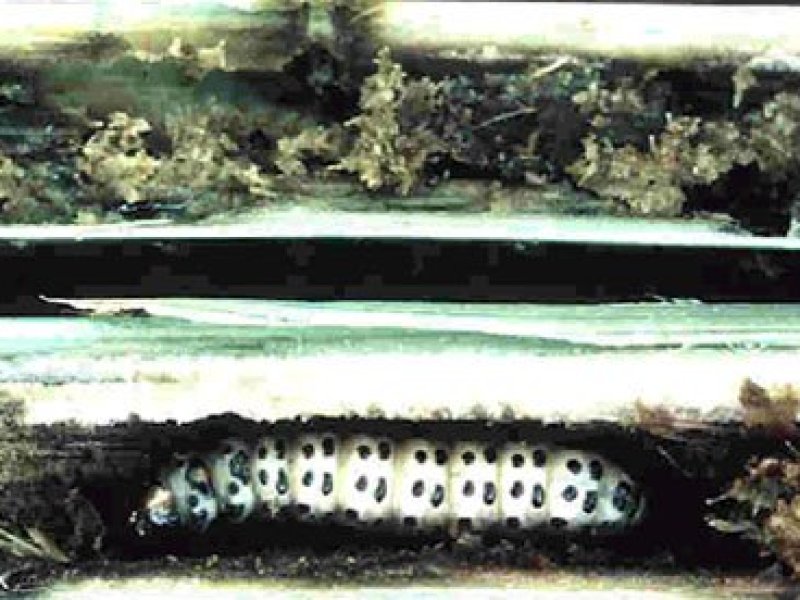

The millet stemborer (Coniesta ignefusalis) It is the dominant stemborer of millet in the Sahelian zone of Africa, and also attacks sorghum, maize, and wild grasses. Major damage has been reported in West Africa. It has also been found causing considerable damage to millet in Western Eritrea, being considered as the major pest of millets in Eritrea (B. Le Ru, icipe, personal communication). The moths have golden brown forewings. They are active throughout the night and during the day rest on the lower surface of leaves or along stems. Caterpillars are cream-coloured with black spots along the body. However in the dry season, when caterpillars enter in diapause (a resting period) they change colour to pale yellow or uniform cream white. They stay in this resting period from 6 to 7 months, but occasionally for more than a year.

Moths lay eggs between the leaf sheet and the stem in batches of 20 to 50 eggs. Caterpillars tunnel in the leaf sheets and in the underlying stem. They normally pupate within the stem. Small plants on which eggs are laid may be thoroughly riddle with caterpillars and soon collapse, but in larger plants external symptoms show two to three weeks after stems have been infested. Economic damage results from early plant death ( "dead-heart") stem tunnelling, disruption of nutrient flow, steam breakage, poor or no grain formation and empty heads. Crop losses have been estimated at $91 million a year. For more information on the African maize stalk borer click here. For more information on the Spotted stalkborer click here. |

|

|

What to do:

|

|

Storage pests: The lesser grain borer (Rhyzopertha dominica) and the khapra beetle (Trogoderma granarium) Grains of pearl millet are attacked by major pests such as the lesser grain borer and the khapra beetle. For this reason, the popular concept that millets are hardly susceptible to damage by storage insect pests is erroneous, except for the very small-grained millets such as tef and fonio. The lesser grain borer and the kapra beetle are relatively well adapted to extremely dry conditions and will cause serious damage to millet. Other secondary storage pests do not thrive in semi-arid climates where millets are grown, where stored grain is typically very dry. Other non-insect pests such as rats and birds may destroy a considerable part of the harvest. |

|

|

What to do:

|

Geographical Distribution in Africa

Geographical Distribution of Millet in Africa. Updated 8th July 2019. Source FAOSTAT

© OpenStreetMap contributors, © OpenMapTiles, GBIF. https://www.gbif.org/species/2706141

Read more

Angola: Masango (P. glaucum)

Ethiopia: Dagussa (Amharic, Sodo); Tokuso (Amharic); Barankiya (Oromo) (E. coracana); Bultuk (Oromo), Dagusa (Amharic) (P. glaucum) (National Academies of Sciences, 1996)

Kenya: Mwee (Kamba); Mwere (Kikuyu, Mbeere, Meru, Embu); Uwele, Mawele (plural), Mwele, Miwele (plural) (Swahil): Erau (Turkana) (P. glaucum); Ugimbi (Embu); Uimbi (Kamba); Ugimbi, Mugimbi (Kikuyu); Obure (Luhya); Kal (Luo); Wimbi, Mwimbi (Swahili) (E. coracana)

Malawi: Mawere, Lipoko, Usanje, Khakwe, Mulimbi, Lupodo, Malesi, Mawe (E. coracana) (National Academies of Sciences, 1996)

Mali: Sanyò, Nyò, Gawri (P. glaucum) (National Academies of Sciences, 1996)

Niger: Hegni (Djerma), Gaouri (Peul), Hatchi (Haussa) (P. glaucum) (National Academies of Sciences, 1996)

Nigeria: Gero (Hausa), Dauro, Maiwa, Emeye (Yoruba) (P. glaucum) (National Academies of Sciences, 1996);

Uganda: Bulo, Ragi, Wimbi (E. coracana)

Sudan: Tailabon (Arabic); Ceyut (Bari) (E. coracana); Dukhon (P. glaucum) (National Academies of Sciences, 1996)

Tanzania: Mbege (Swahili); Mwimbi, wimbi, Ulezi (E. coracana)

Zambia: Kambale, Lupoko, Mawele, Majolothi, Amale, Bule (E. coracana); Mawele, Nyauti, Uchewele (Nyanja), Bubele, Kapelembe, Isansa, Mpyoli (Bemba) (P. glaucum) (National Academies of Sciences, 1996);

Zimbabwe: Rapoko, Zviyo, Njera, Rukweza, Mazhovole, Uphoko, Poho (E. coracana); Mhunga (Chewa), U/Inyawuthi (Ndebele) (P. glaucum) (National Academies of Sciences, 1996);

South Africa: Amabele, Unyaluthi, Unyawoti, Unyawothi (Zulu); Ntweka (Swati); Nyalothi (Sotho); Mhunga, Mhungu (Shona) (P. glaucum) (National Academies of Sciences, 1996)

General Information and Agronomic Aspects

Introduction

Millets refers to a group of small-seeded annual grasses belonging to the family Poaceae (Gramineae). They are often cultivated as cereals and are found in the arid and semiarid regions of the world.

These grasses produce small seeded grains and are often cultivated as cereals. The most widely cultivated species are:

- Pearl millet (Pennisetum glaucum)

- Foxtail millet (Setaria italica)

- Common millet or proso millet (Panicum miliaceum)

- Finger millet (Eleusine coracana)

Millet cultivation dates back thousands of years, with evidence suggesting its domestication in various regions of the world. Pearl millet originated in West Africa, while proso millet was likely domesticated in eastern Europe and Asia. Foxtail millet is believed to have originated in China, and finger millet in East Africa.

Millet has been a staple food in many cultures for centuries. It is consumed in various forms, such as whole grains, flour, porridge, and flatbreads. The husked grain of millet has a slightly nutty flavor and can be eaten whole after roasting or after cooking or boiling like rice. Millet flour is used for making mush, porridge, flat bread or chapati. The flour is also used for making wine or beer. The grain is a feed for animals. The green plant is used as forage, but the quality of the straw is poor. Brooms are made from the straw. Starch from the grains is used for sizing textiles. Some millet varieties will survive drought conditions where maize crops often fail to reach maturity. The popularity of millet fell for some years due to introduction of maize, wheat and rice, but is again on the rise with millers being able to sell far more than is delivered.

Millet is a nutrient-rich grain. It is a good source of complex carbohydrates, dietary fiber, and essential minerals like calcium, iron, magnesium, and phosphorus. Millet is also rich in B vitamins, particularly niacin (vitamin B3) and folate. It is gluten-free, making it suitable for people with gluten sensitivities. Key producers of millet include India, China, Nigeria, Niger, and Mali. India is a major producer and consumer of millet, with pearl millet being an important crop in arid and semi-arid regions. Millet is fast becoming a popular baby food as the grains are rich in calcium and have a pleasant flavour.

Species account

Pearl millet (Pennisetum glaucum)

Pearl millet belongs to the genus Pennisetum that comprises approximately 80 to 140 species varying based on different taxonomic sources and classification systems. Other notable species within the genus Pennisetum include: Napier Grass (Pennisetum purpureum); Purple Fountain Grass (Pennisetum setaceum); Fountain Grass (Pennisetum alopecuroides).

Pearl millet is believed to have originated in Africa, particularly in the Sahel region, but it has been cultivated and adapted in many tropical and subtropical regions across Africa, Asia, and the Americas. The crop is known for its drought tolerance and ability to grow in soils with low fertility

P. glaucum is a tall annual grass, usually 1.5-2.5 m (some varieties up to 5 m) cultivated for its grain. Stems often branched and in many cases several arising from the rootstock. Leaves: slightly hairy, long and narrow. Flowers: head cylindrical, up to 20 cm long (some cultivars up to 50 cm) greenish white at first (due to styles), turning dirty yellow-brown (due to anthers) then grey as grain matures. Large amounts of pollen produced. Fruits: grains 1.5-2.5 mm long, greenish grey, oval and may be conspicuous or, as in some varieties, hidden by long bristles.

Pearl millet is considered as a staple food in Africa and India where it is used to make flour, bread, stiff porridge, "couscous" and making fermented/ non-fermented beverages. The stalks are employed as mulch and are believed to enhance the soil for crops like maize. They are not suitable as animal fodder. The grain is utilized as bird feed.

Crop may be sown by broadcasting or in lines then covered with a little soil. Traditionally several grains are dropped at intervals of about 30 cm. Crop lines can be at intervals of 0.5-0.7 m. Bulrush millet may be intercropped with maize but in different lines. Maize thinly scattered among the millet also gives good results. Grain yields range from 250 kg to 1500 kg/ha, with average 670 kg/ha in Africa and 790 kg/ha in India).

(Maundu et al., 1999, Andrews et al., 2006, National Academies of Sciences, 1996, Heuzé V., Tran G., 2015)

© Maundu, 2003

Ⓒ P Maundu, 2001

Common millet or proso millet (Panicum miliaceum)

Proso millet belongs to the genus Panicum that encompasses about 470 species distributed in tropical and subtropical regions. Other notable species within the genus include: Switchgrass (Panicum virgatum), Guinea grass (Panicum maximum), Hall's panicgrass (Panicum hallii), and Buffelgrass (Panicum coloratum).

P. miliaceum is believed to have originated in Asia, possibly in China. It has a long history of cultivation in various parts of the world. It is now grown across different continents, including Europe, Asia, North America, and Africa. Proso millet is a warm-season annual grass, commonly grown as a late-seeded summer crop. The crop thrives in hot, dry conditions at high elevations (1200-3500 m), it needs 200-400 units of annual rainfall, with 35-40% during its growth period. It's versatile with soil except coarse sand, making it adaptable and valuable for such environments.

Proso millet is an erect annual grass that’s grow to a height of 1.2-1.5 m, usually free-tillering and tufted, with a rather shallow root system. Stems: cylindrical, simple or sparingly branched, with simple alternate and hairy leaves. Inflorescence: is a slender panicle with solitary spikelets. Fruits: a small grain broadly ovoid, up to 3 mm x 2 mm, smooth, variously colored but often white, and shedding easily.

The grains are mainly consumed by humans. They can be boiled liked rice, roasted, turned into porridge, ground, or baked into flatbread. There are sticky (Glutinous) and non-sticky types (Non glutinous). Flour from the Sticky types is used for making bread and cakes, while other types need to be mixed with wheat flour. Non-sticky types can replace wheat for those who can't have gluten. Proso millet flour is also used for making wine or beer. The grain is a feed for animals, including ruminants, pigs, poultry, and pet birds. The green plant serves as forage, but the straw's quality is low. Straw is utilized for creating brooms. Additionally, the starch from the grains is utilized in sizing textiles.

(Tran G., 2015, Kaume, R.N., 2006, PROSEA, 2016)

© Maundu 2005

Foxtail millet (Setaria italica)

The species belongs to the genus Setaria which comprises approximately 100-125 species. Other notable species within the Setaria genus are Green foxtail (Setaria viridis) and Yellow foxtail (Setaria pumila).

Foxtail millet is believed to have originated in East Asia, particularly in China and surrounding regions where it has been cultivated for thousands of years. The crop is now widely grown in countries across Asia, including India, China, Japan, and Korea. It is also cultivated in parts of Europe and Africa. Ecologically, foxtail millet is well-suited to arid and semi-arid regions. It is known for its ability to tolerate drought and grow in poor soils. It's often used in areas with limited water availability or as a secondary crop in regions where the main staple crops may not thrive.

Foxtail millet is a fast growing annual grass that grows to a height of 1 to 1.5 meters. Stems: erect, slender and tiller from the base. Leaves: alternate with lanceolate and serrated blades, 15-50 cm long and 0.5-4 cm broad. Inflorescences: The inflorescence is an erect or pendulous spike-like bristly panicle bearing 6 to 12 spikelets. Grains: small, oval-shaped, and vary in color from white and yellow to brown.

Foxtail millet is a dual-purpose plant grown for its grain, which is used for human food and livestock fodder. The grain is a dietary staple in Asia, southeastern Europe, and northern Africa. It can be cooked like rice, whole or broken, or ground into flour often mixed with wheat flour and used to make unleavened or leavened bread. The flour is also used to make various traditional dishes such as porridges, bread, and fermented products in recent years, foxtail millet has gained attention as a nutritious and gluten-free alternative to wheat and rice.

(Brink, M., 2006, National Academies of Sciences, 1996 Heuzé V., et al., 2015, PROSEEA, 2016)

Finger millet (Eleusine coracana)

The species belongs to the Eleusine genus that comprises about 10 species. The species is believed to have originated in East Africa, particularly in the highlands of Ethiopia and Uganda. From its origin, it has spread to various parts of the world. It is now cultivated in several countries across Asia and Africa.

E. coracana is a grass usually 0.5-1 m high. Flowers: Head dirty green and branched into 5-7 spikes (fingers) usually 5-10 cm long. Fruits: Grain usually reddish brown, dark brown or occasionally cream.

Finger millet thrives in hot conditions, with optimal temperatures of 18-27°C, and can tolerate cooler climates than other millets. It grows at altitudes between 500-2400 m and requires well-distributed rainfall ranging from 500-1000 mm. Dry weather is necessary during harvest for grain drying. It can adapt to various soils but performs best on reddish-brown lateritic soils with good drainage and water holding capacity, containing iron and aluminum. Finger millet also tolerates waterlogging and has a superior ability to utilize rock phosphate compared to other cereals.

Fingermillet is a staple food in many African and Asian countries. It is considered an important famine crop because the grain stores extremely well stored for lean years. The grains are ground into nutrient-rich flour for traditional dishes like porridge and flatbreads. The flour is often mixed with other flours (e.g from sorghum, cassava or maize) in these preparations.

Finger millet is also used to make liquor ("arake" or "areki" in Ethiopia) and beer, which yields by-products used for livestock feeding. Finger millet grain is not widely used for livestock: not only is it primarily a food grain, but it is of lesser quality for livestock than maize, sorghum and pearl millet. Old stems have a silky lustre and are used as material for plaiting.

(Maundu et al., 1999, De Wet, J.M.J., 2006, National Academies of Sciences, 1996,)

© Maundu 2005

Ⓒ Foods of Nairobi people, 2001

Ⓒ Foods of Nairobi people, 2001.

Millet Varieties

Varieties in Kenya

A lot of work has been done to identify improved varieties of millet to be grown under different ecological zones of Kenya.

Some recommended varieties of finger millets and their characteristics (Kenya)

|

| Finger Millet |

|

© A.A.Seif, icipe |

| Variety | Optimal production altitude (masl) |

Maturity (Months) |

Grain colour | Potential grain yield (90 kg bags/acre) |

Special attributes |

| "P 224" | 1150-1750 | 3-4 | Brown | 10 | Tolerant to lodging and blast |

| "Gulu E" | 250-1500 | 4 | Brown | 8 | - |

| "KAT/FMI" | 250-1150 | 3 | Brown | 7 | Drought tolerant. Tolerant to blast. High in calcium |

| "Lanet/FM1" | 1750-2300 | 5-7 | Brown | 7 | Tolerant to cold and drought |

Examples of finger millet varieties in Uganda

- "PESE 1"

- "PESE 2"

- "SEREMI 1"

- "SEREMI 2"

- "SEREMI 3"

Some recommended varieties of pearl millets and their characteristics (Kenya)

|

| Pearl Millet |

|

© A.A.Seif, icipe |

| Variety | Optimal production altitude (masl) |

Maturity (Months) |

Grain colour | Potential grain yield (90 kg bags/acre) |

Special attributes |

| "KAT/PM1" | 250-1150 | 2-3 | Grey | 8 | Tolerant to bird damage, leaf blight and rust |

| "KAT/PM2" | 250-1150 | 2 | Grey | 7 | Tolerant to leaf blight and rust. Grain used at dough stage |

| "KAT/PM3" | 50-1500 | 2-3 | Grey | 10 | Tolerant to leaf blight and rust |

Examples of pearl millet varieties in Tanzania

- "Okoa" (Altitude recommended: 0-1300 m; grain yield: 2.0-2.5 t/ha; grain colour: grey; days to flowering: 87-92; resistant to Striga spp.; tolerant to ergot)

- "Shibe" (Altitude recommended: 0-1200 m; grain yield: 1.8-2.0 t/ha; grain colour: grey; days to flowering: 90-95; resistant to Striga spp.)

|

| Proso Millet |

|

© A. A.Seif, icipe |

| Crop | Variety | Optimal production altitude (masl) |

Maturity (Months) |

Grain colour | Potential grain yield (90 kg bags/acre) |

Special attributes |

| Proso millet | "KAT/PRO-1" | 0-2000 | 2.5 | Cream | 7 | Has ability to stop growing during severe water stress and to resume growth quickly when the stress is broken |

| Fox tail millet | "KAT/FOX-1" | 250-1500 | 3-4 | Cream | 8 | - |

Proso and fox tail millets can be grown in all areas whereas "Gulu E" does best on coast and moist mid altitude. KAT/FM1 is recommended for semi-arid lowlands and Lanet/FM1 for cold semi arid highlands.

Ecological information

Millet is mostly grown in temperate and subtropical regions. It is adapted to conditions that are too hot and too dry, and to soils too shallow and poor for successful cultivation of other cereals. It is tolerant to a very wide temperature range but susceptible to frost. Cultivation occurs up to 3000 m altitude in the Himalayas. In Kenya millet is grown from 0 - 2400 m above sea level. Proso millet has one of the lowest water requirements of all cereals. An average annual rainfall of 200 - 450 mm is sufficient, of which 35 - 40% should fall during the growing period. Most soils are suitable for its cultivation, except coarse sand.

Agronomic aspects

Selection of healthy seeds, free from bird and insect damage and diseases, is important to produce vigorous seedlings that could fare well in case of attack by pests or diseases. Prepare seed for sowing by threshing it (if at all stored on the head) and removing all mixtures such as glumes, bits of the rachis and peduncle, etc. This can be done by winnowing and occasionally by sieving. These processes also remove light and small seeds. A fast, easy and efficient method of quality seed selection uses a 10% salt solution to separate good seeds from bad seeds. The salt solution enhances the flotation of light and damaged seeds, fungal spores and light foreign matter. The good and heavy seeds and pebbles drop to the bottom. The floating portion is decanted and discarded and the sunken portion subjected to flotation one or two more times, after which the good seeds at the bottom are rinsed with clean water to remove excess salt. This portion is then sun-dried. After drying, the pebbles are removed by hand picking (DFPV, Niger).

Early land preparation is recommended. Millet requires a fine seedbed suitable for small grains, to ensure good germination, plant population density and effective weed control. If tractors or oxen are used to open up land for planting, it is advisable to harrow it after the first ploughing. When jembes (hand hoes) are used for land preparation, farmers are advised to break large clods to provide a smooth seedbed. Plant before or at the onset of rains by either drilling in the furrows made by oxen plough or tractor or by using a panga (cutlass) for hand planting in hills.

Spacing and seed rate

If the population is too high at emergence, thin when plants are about 15 cm tall, 2 weeks after emergence. Seed rate (when planted in furrows):

• Finger millet - 3 kg/ha

• Pearl millet - 5 kg/ha

• Fox tail millet - 4 kg/ha

• Proso millet - 4 kg/ha

For sole cropping the following distances should be followed:

• Pearl millet varieties: 15 cm between seeds and 60 cm between rows

• Finger millet, foxtail and Proso millet: 10 cm between seeds and 30 cm between rows.

Husbandry

Millet benefits from intercropping with legumes such as green gram and cowpeas. It can also be rotated with legume crops to benefit from the soil improvement facilitated by these crops or intercropped with other non-cereal crops. Application of farmyard manure at 8-10 tons/ha is recommended in order to improve the soil organic matter content, moisture retention ability and soil structure. Phosphorous should be applied in the form of rock phosphate. Weeding should be done twice, first time 2-3 weeks after emergence and second weeding about two weeks later.

Harvest, post-harvest practices and markets

Harvesting

Millet grains should be harvested as soon as they are physiologically mature about 2-4 months after sowing, when the grain has a moisture content of 14-15%. Millet do not mature uniformly, hence multiple stage harvesting could be required after the ears turn brown. First harvest is done when the ear of main shoot and 50% of ear turn brown. A week later the second harvest is done where rest of the head is removed. The second harvest contained green heads hence it is recommended to keep them under shade for a few days to hasten drying. Individual heads are cut off with a knife, leaving a few centimeters of stalk attached.

Avoid delayed harvesting, as the seed shatters easily. If millet is harvested during the rainy season with high relative humidity, the grain must be dried to 14% moisture content. In African households, millet is usually dried above the domestic fire.

(KALRO, 2021, Kaume, R.N., 2006, PROSEA, 2016)

Post-harvest practices

After harvesting the millet heads are piled in heaps for a few days to promote fermentation whose heat and hydrolysis makes the seeds easier to thresh. The panicles should be kept off the soil on raised platforms, mats, or trays while drying for threshing. The heads are threshed using conventional beating with sticks and grain is winnowed. Machine threshing is not common in developing countries. The threshed grain should be dried by spread the grain thinly on the drying surface to allow air to pass through it and turn the grain regularly to avoid overheating. Protect the grain from rain, insects, animals and dirt. The grain stores well for up to five years. Sometimes the grain is mixed with ash or slightly baked before storage. Because of its small size, the grain is barely susceptible to insect attack.

(KALRO, 2021, Kaume, R.N., 2006, PROSEA, 2016)

Value addition and markets

Millet is commonly utilized within its local regions and, due to its rapid maturation, it can help bridge periods of scarcity before the main harvest of other cereal crops takes place. According to Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), global millet production was estimated at 28.33 million metric tons in 2019, which increased to 30.08 million metric tons in 2021. India, Niger, and China are the largest millet producers in the world, accounting for more than 55.0% of global production. India is the largest producer of millet in the world. Production statistics for individual millet species are scarce because they are usually lumped with those of other millets. Pearl Millets however have the highest market share in the world mainly due to the high rate of consumption and the high rate of production.

(PROSEA, 2016, Kaume, R.N., 2006.

Nutrition value

Millet, a group of small-seeded grains, boasts impressive nutritional value and numerous health benefits. The grains are rich in complex carbohydrates, millet's low glycemic index contributes to weight management and may assist in diabetes control. Its high fiber content supports digestive health by promoting regular bowel movements and aiding in the prevention of constipation

Millet is notably gluten-free, rendering it suitable for individuals with gluten sensitivities or celiac disease. Moreover, it contains an array of vitamins and minerals, including B-vitamins (such as niacin and thiamin), magnesium, phosphorus, and iron, which collectively contribute to optimal metabolic function, nerve health, bone strength, and red blood cell production. The presence of antioxidants in millet, including phenolic compounds, helps combat oxidative stress and reduce the risk of chronic diseases like heart disease and certain types of cancer.

Millet is a high-energy, nutritious cereal. It is particularly recommended for children, lactating mothers, convalescents and the elderly. Some of the healthy benefits of millet includes; prevention of certain types of cancer, help control diabetes, offer a dietary option for people with Celiac disease, improve digestive health, build strong bones, promote red blood cell development, and boost energy and fuel production.

(Healthline (n.d)

Further reading

• https://www.healthline.com/nutrition/what-is-millet#benefits

Table 1:Proximate nutritional value of 100g edible portion

Code Food Name |

Millet, bulrush, grain, dry, raw |

Millet, bulrush, whole, grain, dry, boiled, drained (without salt) |

Millet, bulrush, flour |

Recommended daily allowance (approx.) for adults a |

Edible conversion factor |

1 |

1 |

1 |

|

Energy (kJ) |

1490 |

623 |

1490 |

9623 |

Energy (kcal) |

354 |

148 |

354 |

2300 |

Water (g) |

11 |

62.9 |

11 |

2000-3000c |

Protein (g) |

9.8 |

4.1 |

10.5 |

50 |

Fat (g) |

5.3 |

2.2 |

5.3 |

<30 (male), <20 (female)b |

Carbohydrate available (g) |

62.5 |

26 |

61.8 |

225 -325g |

Fibre (g) |

8.8 |

3.6 |

8.8 |

30d |

Ash (g) |

2.7 |

1.1 |

2.7 |

|

Minerals |

||||

Ca (mg) |

32 |

15 |

32 |

800 |

Fe (mg) |

6.3 |

2.6 |

32.4 |

14 |

Mg (mg) |

84 |

36 |

84 |

300 |

P (mg) |

427 |

169 |

263 |

800 |

K (mg) |

291 |

97 |

291 |

4,700f |

Na (mg) |

4 |

3 |

4 |

<2300e |

Zn (mg) |

4.14 |

1.64 |

4.14 |

15 |

Se (mcg) |

25 |

11 |

34 |

30 |

Bioctive compounds. |

||||

Vit A RAE (mcg) |

2 |

1 |

0 |

800 |

Vit A RE (mcg) |

5 |

2 |

0 |

800 |

Retinol (mcg) |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1000 |

b-carotene |

28 |

11 |

0 |

600 – 1500g |

Thiamin (mg) |

0.27 |

0.06 |

0.27 |

1.4 |

Riboflavin (mg) |

0.17 |

0.05 |

0.17 |

1.6 |

Niacin (mg) |

1.5 |

0.5 |

1.5 |

18 |

Dietary Folate Eq. (mcg) |

162 |

47 |

162 |

400f |

Food folate (mcg) |

162 |

47 |

162 |

400f |

Vit B12 (mg) |

0 |

0 |

0 |

3 |

Vit C (mg) |

[3] |

1 |

3 |

60 |

Source (Nutrient data): FAO/Government of Kenya. 2018. Kenya Food Composition Tables. Nairobi, 254 pp. http://www.fao.org/3/I9120EN/i9120en.pdf

a Lewis, J. 2019. Codex nutrient reference values. Rome. FAO and WHO

b NHS (refers to saturated fat)

c https://www.hsph.harvard.edu/nutritionsource/water/

d British Heart Foundation

e FDA

f NIH

g Mayo Clinic

hWest African food composition table, https://www.fao.org/3/ca7779b/CA7779B.PDF

Nutritive Value per 100 g of edible Portion

| Raw or Cooked Millet | Food Energy (Calories / %Daily Value*) |

Carbohydrates (g / %DV) |

Fat (g / %DV) |

Protein (g / %DV) |

Calcium (g / %DV) |

Phosphorus (mg / %DV) |

Iron (mg / %DV) |

Potassium (mg / %DV) |

Vitamin A (I.U) |

Vitamin C (I.U) |

Vitamin B 6 (I.U) |

Vitamin B 12 (I.U) |

Thiamine (mg / %DV) |

Riboflavin (mg / %DV) |

Ash (g / %DV) |

| Millet cooked | 119 / 6% | 23.7 / 8% | 1.0 / 2% | 3.5 / 7% | 3.0 / 0% | 100.0 / 10% | 0.6 / 3% | 62.0 / 2% | 3.0 IU / 0% | 0.0 / 0% | 0.1 / 5% | 0.0 / 0% | 0.1 / 7% | 0.1 / 5% | 0.4 |

| Millet puffed | 354 / 18% | 80.0 / 27% | 3.4 / 5% | 13.0 / 26% | 8.0 / 1% | 266 / 27% | 2.8 / 16% | 40.0 / 1% | 0.0 IU / 0% | 0.0 / 0% | 0.4 / 18% | 0.0 / 0% | 0.4 / 26% | 0.3 / 16% | 1.6 |

| Millet raw | 378 / 19% | 72.9 / 24% | 4.2 / 6% | 11.0 / 22% | 8.0 / 1% | 285 / 28% | 3.0 / 17% | 195 / 6% | 0.0 IU / 0% | 0.0 / 0% | 0.4 / 19% | 0.0 / 0% | 0.4 / 28% | 0.3 / 17% | 3.3 |

*Percent Daily Values (DV) are based on a 2000 calorie diet. Your daily values may be higher or lower, depending on your calorie needs.

Recipes

1. Ugali (Mixed flours)

(From Kenya)

Ingredients

- 4 cups of mixed flour (finger millet, pearl millet, sorghum, cassava)

- 5 cups of water

Procedure

- Boil 5 cups of water in a pot

- Mix the 4 types of flour. Add the flours little by little while stirring constantly until it develops a stiff consistency

- Stir well until no lumps are left

- Lower the heat, cover the pan and cook for 15 minutes

- Stir again and mould it into a round shape and serve

- Serve with any sauce or vegetable

2. Tô (stiff porridge)

(Burkina Faso)

Ingredients

- Pearl millet flour (suggested quantity – 2 cups/3 persons)

- Water for cooking (depends on quantity of flour, 1½ cups water to 1 cup flour is recommended)

Procedure

- Heat the water in a suitable saucepan

- When water is hot to the touch, lower heat and gently add the cereal flour, stirring constantly with a wooden spoon or spatula with each addition, and making a smooth paste

- When all flour is used up, increase the heat slightly still stirring, but this time briskly to remove any lumps. If batter is stiff after addition of flour, add a little water to turn it into a workable paste

- Cover pot and allow cooking under low heat for 10 minutes

- Stir vigorously this time so that dough has a smooth consistency

- (If dough is too stiff, blend in some more water a little at a time until the desired consistency is obtained. The tô is cooked when it is soft and leaves the sides of the pot)

- Serve warm tô with any mucilaginous soup or savoury sauce

Note:Fonio, sorghum, maize or any combinations of these flours can also be used.

(Source: F. Smith, 2005)

3. Couscous

Ingredients

- 10 cups cereal flour (pearl millet, sorghum, maize or hungry rice)

- 1 heaped teaspoon dry baobab leaf or dry okro powder

- Water for mixing and steaming

Procedure

- Sieve flour with 1mm sieve to ensure an adequately fine starter product

- Pour flour in a bowl and sprinkle with about 2 cups cold water, mix and rub wetted flour between both palms to form sand-like aggregates

- Prepare the steamer for steaming

- Sieve the granulated product with a 1.5 mm mesh sieve

- Put the sieved cereal granules on the top part of the double boiler (steamer) and steam for15 minutes

- Take out the steamed granules which should now form a single mass, put into a convenient bowl and break it up into particles again

- Put the granules back into the steamer and steam for another 15 minutes

- Take out again the formed mass and break up into aggregates, sieve the resulting particles with a 2.5 mm sieve

- If for later consumption (storage), sun dry the sieved cereal granules until grains are no longer moist to touch, then store in a tight lidded container

- For immediate consumption, sprinkle sieved granules with 3½ to 4 cups water and mix thoroughly with the fingers, add one heaped teaspoon of baobab* leaf powder or dry okro powder, mix thoroughly again

- Put mixture back in the steamer and steam again for 15 minutes

- Cool cooked couscous slowly and serve warm with peanut soup or couscous sauce

Yields 8 servings

Remarks

*Powdered dry baobab leaf (Adansonia digitata or dry okro powder is used locally to prevent the cereal granules from sticking together during the final steaming process. Where these are not available, a teaspoon of peanut oil or any light cooking oil, or a blob of margarine will produce the same effect.

(Source: F. Smith, 2005)

4. Obaga (Pearl millet porridge)

(Gogo, Dodoma, Tanzania)

Ingredients

- Pearl millet flour

- Milk/Sugar

- Mafuta ya samhi (ghee)

- Mabuyu (baobab pulp)

- Water

Procedure

- Clean the grain

- Pound once

- Winnow to remove dirt.

- Grind to flour

- Take a little flour, mix with cold water

- Pour into boiling water

- Stir and let it boil for a few minutes

- Mix with milk or/and sugar

- Add ghee, baobab pulp and sugar

- Serve

5. Ngima ya nyunyi (stiff porridge with vegetable)

(Kamba, Kitui, Kenya)

Ingredients

- 3 handfuls of vegetables (cowpea)

- 3 tablespoons ghee

- ½ Kg pearl millet flour

Method

- Wash the vegetable well

- Cut finely

- Put in a sufuria (metal pot) to boil for 10 minutes

- Add salt to taste

- Remove from heat source after it cooks

- Add pearl millet flour to the vegetable little by little while stirring till it hardens to ugali

- Stir well to have an even mixture

- Cook for 15 minutes

- Make a hole in the middle of the ugali and add ghee

- Simmer for 5 minutes

- Mould into a round shape

- Serve it warm

- Usually served alone as it has vegetables

(Source: Adeka et al., 2005)

6. Ndua (porridge)

(Kamba, Kitui, Kenya)

Ingredients

- 3 cups of pearl millet flour

- 1 cup of tamarind juice

- Sugar to taste

Method

- Boil 4 cups of water

- Add pearl millet flour little by little to make thin porridge while stirring vigorously with kipekecho (stirring rod)

- The porridge has lumps (makindi)

- Add 1 cup of tamarind juice, sugar to taste

- Cook for 10 minutes

- Serve hot

(Source: Maundu et al., 2005)

| African armyworm (Spodoptera exempta) It is usually an occasional pest, but when outbreaks occur damage to millet can be devastating. The caterpillars eat the above-ground parts of the plants leaving only the base of the stem. What to do:

|

| Several species of stemborers attack millet including the millet stemborer (Coniesta ignefusalis), the maize stalkborer (Busseola fusca), the spotted stalkborer (Chilo partellus), and the pink stalkborer (Sesamia calamitis). Stemborer caterpillars bore into stems of millets disrupting the flow of nutrient from the roots to the upper parts of plants. Attack on young millet plants causes damage known as "dead hearts". In older plants the top part of the stem dies as a result of tunnelling by the borers.

The millet stemborer (Coniesta ignefusalis) It is the dominant stemborer of millet in the Sahelian zone of Africa, and also attacks sorghum, maize, and wild grasses. Major damage has been reported in West Africa. It has also been found causing considerable damage to millet in Western Eritrea, being considered as the major pest of millets in Eritrea (B. Le Ru, icipe, personal communication). The moths have golden brown forewings. They are active throughout the night and during the day rest on the lower surface of leaves or along stems. Caterpillars are cream-coloured with black spots along the body. However in the dry season, when caterpillars enter in diapause (a resting period) they change colour to pale yellow or uniform cream white. They stay in this resting period from 6 to 7 months, but occasionally for more than a year.

Moths lay eggs between the leaf sheet and the stem in batches of 20 to 50 eggs. Caterpillars tunnel in the leaf sheets and in the underlying stem. They normally pupate within the stem. Small plants on which eggs are laid may be thoroughly riddle with caterpillars and soon collapse, but in larger plants external symptoms show two to three weeks after stems have been infested. Economic damage results from early plant death ( "dead-heart") stem tunnelling, disruption of nutrient flow, steam breakage, poor or no grain formation and empty heads. Crop losses have been estimated at $91 million a year. For more information on the African maize stalk borer click here. For more information on the Spotted stalkborer click here. What to do:

|

| Millet head miner (Heliocheilus albipunctella) It is the most important insect pest of pearl millet in the Sahel. Moths deposit their eggs on the heads of millet, preferring half-emerged and fully-emerged flowering heads. The caterpillars mine into the seeds of the millet head, damaging the millet panicle (i.e. the flower head, where the grain is formed). It has been reported to cause complete crop loss. Pupation takes place in the soil.

What to do:

|

| Shoot fly (Atherigona soccata) Sorghum shoot fly, (Atherigona soccata), is a particularly nasty pest of sorghum in Asia, Africa, and the Mediterranean area. Females lay single cigar-shaped eggs on the undersides of leaves at the 1- to 7-leaf stage. The eggs hatch after only a day or two of incubation, and the larvae cut the growing point of the leaf, resulting in wilting and drying. These leaves, known as 'deadhearts', are easily plucked. When a "dead heart" is plucked, it releases an obnoxious odor. Adult resemble small houseflies. They are about 0.5 cm long. The shoot fly has been reported as attacking pearl millet. Damage occurs 1-4 weeks after seedling emergence. The damaged plants produce side tillers, which may also be attacked. The shoot fly's entire life cycle is completed in 17-21 days. Infestations are especially high when sorghum planting is staggered due to erratic rainfall. Temperatures above 35°C and below 18°C reduce shoot fly survival, as does continuous rainfall. What to do:

|

| Several species of grasshoppers attack millets. Short-horned grasshoppers include Zonocerus spp, Oedaleus senegalensis, Kraussaria angulifera, Hieroglyphus daganensis, Diabolocantatops axillaris among others. The long horned edible grasshopper (Homorocoryphus niditulus) is a pest in East Africa. Grasshoppers defoliate and eat the panicles. They are not of economic importance when present in low numbers. However, invasion by a swarm of grasshoppers may result in serious grain losses.

What to do:

|

| Grains of pearl millet are attacked by major pests such as the lesser grain borer and the khapra beetle. For this reason, the popular concept that millets are hardly susceptible to damage by storage insect pests is erroneous, except for the very small-grained millets such as tef and fonio. The lesser grain borer and the kapra beetle are relatively well adapted to extremely dry conditions and will cause serious damage to millet. Other secondary storage pests do not thrive in semi-arid climates where millets are grown, where stored grain is typically very dry. Other non-insect pests such as rats and birds may destroy a considerable part of the harvest. What to do:

|

| Stemborers: African maize stalkborer (Busseola fusca) Stemborers are the most important insect pests of maize in sub-Saharan Africa. Yield losses vary between 10-70%. Several species have been reported. The importance of a species varies between regions, within a country or even the same eco-region of neighbouring countries. At least four species attack maize in eastern and southern Africa, with yield losses reported to vary from 20 to 40%, depending on agroecological conditions, crop cultivars, agronomic practices and intensity of infestation.

The most important are the African maize stalkborer (Busseola fusca) and the spotted stemborer (Chilo partellus) (see also below).

The pink stalkborer (Sesamia calamistis) and the sugarcane stalkborer (Eldana saccharina) are of minor importance in maize.

Early warning signs: Young plants have pinholes in straight lines across the newest leaves. This is the time to treat - before the caterpillars move into the stem. What to do:

|

| Mealybugs are small, flat, soft bodied insects covered with a distinctive segmentation. Their body is covered with a white woolly secretion. They suck sap from tender leaves, petioles and fruits. Seriously attacked leaves turn yellow and eventually dry. This can lead to shedding of leaves, inflorescences, and young fruit. Mealybugs excrete honeydew on which sooty mould developed. Heavy coating with honeydew blackens the leaves, branches and fruit. This reduces photosynthesis, can cause leaf drop and affect the market value of the fruit.

A wide range of natural enemies attacks mealybugs. The most important are ladybird beetles, hover flies, lacewings, and parasitic wasps. These natural enemies usually control mealybugs. However, mealybugs can cause economic damage to mango when natural enemies are disturbed (for instance by ants feeding on honeydew produced by mealybugs or other insects) or killed by broad-spectrum pesticides, or when mealybugs are introduced to new areas, where there are no efficient natural enemies.

The latter is the case of two serious mealybug pests on mangoes in Africa: Rastrococcus invadens in West and Central Africa and Rastrococcus iceryoides in East Africa. These mealybugs, of Asian origin, were introduced into Africa, where they developed into serious pests since the natural enemies present were not able to control them. They cause shedding of leaves, inflorescences and young fruits. In addition, sooty moulds growing on honeydews excreted by the insects render the fruits unmarketable and the trees unsuitable for shading. They cause direct damage to fruits leading to 40 to 80% losses depending on locality, variety and season. Rastrococcus invadens was brought under control in West and Central Africa by two parasitic wasps (Gyranusoidea tebygi and Anagyrus mangicola) introduced from India (Neuenschwander, 2003).

Rastrococcus iceryoides is a major pest of mango in East Africa, mainly Tanzania and coastal Kenya. Although several natural enemies are known to attack this mealybug in its aboriginal home of southern Asia (Tandon and Lal, 1978; CABI, 2000), none have been introduced so far into Africa (ICIPE). Insecticides do not generally provide adequate control of mealybugs owing to their wax coating. What to do:

|

| Cream to pink sticky "honeydew" droplets ooze out of infected florets on panicles. Within 10 to 15 days, the droplets dry and harden, and dark brown to black sclerotia (fungal fruiting bodies) develop in place of seeds on the panicle. Sclerotia are larger than seed and irregularly shaped, and generally get mixed with the grain during threshing. Conditions favouring the disease are relative humidity greater than 80%, and temperatures between 20 to 30 degC. The sclerotia falling on the soil or planted with the seed germinate when the plants are flowering. They produce spores that are wind-borne to the flowers, where they invade the young kernels and replace the kernels with fungal growth. The fungal growth bears millions of tiny spores in a sticky, sweet, honeydew mass. These spores are carried by insects or splashed by rain to infect other kernels.

What to do:

|

| Lesions on foliage are elliptical or diamond-shaped, approximately 3 x 2 mm. Lesion centres are grey and water-soaked when fresh but turn brown upon drying. Lesions are often surrounded by a chlorotic halo, which will turn necrotic giving the appearance of concentric rings. The disease is favoured by hot, humid conditions.

What to do:

|

| Long smut (Tolyposporium penicillariae) Immature, green fungal bodies (sori) larger than the seed develop on panicles during grain fill. A single fungal body (sorus) develops per floret. As grain matures, sori change in colour from green to dark brown. Sori are filled with dark spores. Infection takes place at temperature range of between 21 and 31°C, and at relative humidity greater than 80%. The disease is spread by wind-borne spores and rain.

What to do:

|

| Crazy top downy mildew (Sclerospora graminicola) Symptoms often vary as a result of systemic infection. Leaf symptoms begin as chlorosis at the base and successively higher leaves show progressively greater chlorosis. On the lower leaf surface of infected leaves greyish white fungal growth may be observed. Severely infected plants are generally stunted and do not produce panicles. Green ear symptoms result from transformation of floral parts into leafy structures. The disease is prevalent during rainy seasons.

What to do:

|

References and information links

References

- AIC (2002). Field Crops Technical Handbook.

- ARS Agricultural Handbook No. 716: Diseases of Pearl Millet. www.tifton.uga.edu

- CAB International (2005). Crop Protection Compendium, 2005 edition. Wallingford, UK www.cabi.org

- Maundu, P. M., Ngugi, G. W., & Kabuye, C. H. (1999). Traditional food plants of Kenya. (No Title).

- Harris, K. M. (1962). Lepidopterous stem borers of cereals in Nigeria. Vol 53. 139-171

- ICRISAT. Millet production growing in Africa. designs improved cropping systems for Sahelian millet, cowpeas. www.worldbank.org

- Integrated management project of the millet head miner for increasing millet production in the Sahelian zone. www.ccrp.org

- INPhO, Post harvest compendium. Millet. www.fao.org

- Kaume, R.N., 2006. Panicum miliaceum L. [Internet] Record from PROTA4U. Brink, M. & Belay, G. (Editors). PROTA (Plant Resources of Tropical Africa / Ressources végétales de l’Afrique tropicale), Wageningen, Netherlands. <http://www.prota4u.org/search.asp>. Accessed 1 December 2021.

- 10. Maymoona, A.E., Roth, M. (2007). Utilisation of diversitcharacteristics of the millet worm Heliocheilus albipunctella (Lepidoptera: noctuidae) a pest on millet in Sudan. Tropentag, October 9-11, 2007, Witzenhausen. www.tropentag.de

- National Research Council. 1996. Lost Crops of Africa: Volume I: Grains. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. Available online: www.nap.edu

- Nutrition Data www.nutritiondata.com.

- Oduro, K.A. (2000). Checklist of Plant Pests in Ghana. Volume 1: Diseases. Ministry of Food and Agriculture. Plant Protection and Regulatory Services Directorate.

- Pheromone-based monitoring system to manage the millet stem borer Coniesta ignefusalis(Lepidoptera: Pyralidae). ICRISAT. www.icrisat.org

- Youdeowei, A. (2002). Integrated Pest Management Practices for the Production of Cereals and Pulses. Integrated Pest Management Extension Guide 2. Ministry of Food and Agriculture (MOFA) Plant Protection and Regulatory Services Directorate (PPRSD), Ghana, with German Development Cooperation (GTZ). ISBN: 9988 0 1086 9.

- Youm, O., Harris, K. M., Nwanze, K. F. (1996). Coniesta ignefusalis (Hampson), the millet stem borer: a handbook of information. Information Bulletin, no 46. Patancheru 502324, Andhra Pradesh, India: International Crops Research Institute for the Semi-Arid Tropics. 60 pp. ISBN 92-9066-253-0.

- de Wet, J.M.J., 2006. Eleusine coracana (L.) Gaertn. In: Brink, M. & Belay, G. (Editors). PROTA (Plant Resources of Tropical Africa / Ressources végétales de l’Afrique tropicale), Wageningen, Netherlands. Accessed 22 August 2023.

- Brink, M., 2006. Setaria italica (L.) P.Beauv. In: Brink, M. & Belay, G. (Editors). PROTA (Plant Resources of Tropical Africa / Ressources végétales de l’Afrique tropicale), Wageningen, Netherlands. Accessed 22 August 2023.

- Andrews, D.J. & Kumar, K.A., 2006. Pennisetum glaucum (L.) R.Br. In: Brink, M. & Belay, G. (Editors). PROTA (Plant Resources of Tropical Africa / Ressources végétales de l’Afrique tropicale), Wageningen, Netherlands. Accessed 22 August 2023.

- National Research Council. (1996). Lost crops of Africa: volume I: grains. National Academies Press.

- Heuzé V., Tran G., 2015. Pearl millet (Pennisetum glaucum), grain. Feedipedia, a programme by INRAE, CIRAD, AFZ and FAO. https://www.feedipedia.org/node/724 Last updated on September 30, 2015, 14:00

- Tran G., 2015. Proso millet (Panicum miliaceum), grain. Feedipedia, a programme by INRAE, CIRAD, AFZ and FAO. https://www.feedipedia.org/node/722 Last updated on October 2, 2015, 16:16

- Kaume, R.N., 2006. Panicum miliaceum L. In: Brink, M. & Belay, G. (Editors). PROTA (Plant Resources of Tropical Africa / Ressources végétales de l’Afrique tropicale), Wageningen, Netherlands. Accessed 23 August 2023.

- Heuzé V., Tran G., Sauvant D., Bastianelli D., Lebas F., 2015. Foxtail millet (Setaria italica), grain. Feedipedia, a programme by INRAE, CIRAD, AFZ and FAO. https://feedipedia.org/node/725 Last updated on May 11, 2015, 14:34

Information links

• https://plantvillage.psu.edu/topics/pearl-millet/infos

• https://uses.plantnet-project.org/en/Panicum_miliaceum_(PROSEA)

• https://www.mordorintelligence.com/industry-reports/millets-market#:~:text=According%20to%20Food%20and%20Agriculture,million%20metric%20tons%20in%202021.

Contacts information

1. Millet buyers and importers. https://importer.tradeford.com/millet

2. Directory of Millet Suppliers & manufacturers in World. https://www.volza.com/suppliers-global/global-exporters-suppliers-of-millet

Review Process

Dr. Patrick Maundu, James Kioko, Charei Munene and Monique Hunziker, July 2024