|

African citrus psyllid (Trioza erytreaea) The citrus psyllid prefers cool climates and it is found in Kenya only at elevations above 800 m. The adult is about 2 mm long, brownish yellow with long transparent wings with market veins. They resemble winged aphids. The adults jump and fly short distances when disturbed. When feeding, adults take up a distinctive position, with the abdomen raised. The orange-yellow eggs are laid on the edges of tender young leaves. They can be distinguished with the naked eye as a yellow fringe to the leaf. After hatching the nymph moves only a very short distance and settles down to feed on the underside of leaves. Once settled, it does not move again unless disturbed. They resemble small green or yellow scale insects, and are up about 1 mm long. Parasitised nymphs are dark brown to black in colour. Pit-like depressions are formed beneath the nymphs bodies. These depressions look like raised bumps on the upper side of the leaves, and remain even after the nymphs have become adults. As result of these pock marks young leaves may be severely deformed, and flush growth depressed. They also cause damage by sucking sap from the leaves. However, in general, these types of damage do not seriously affect infested trees. The main damage caused by the citrus psyllid is as the vector of the greening disease, a major disease of citrus. A few psyllids in an orchard can spread the greening disease, but when high numbers are present, the spread is particularly rapid. It is therefore necessary to manage the citrus psyllids to retard the spread of the greening disease. |

|

|

What to do:

|

|

Anthracnose (Colletotrichum spp.) There are 3 anthracnose diseases of citrus caused by Colletotrichum spp. Post-bloom fruit drop, which affects flowers of all citrus species and induces drop of fruitlets and is caused by C. acutatum. Lime anthracnose, which attacks all juvenile tissues of only Mexican lime, is also caused by this Colletotrichum species. C. gloeosporioides causes a rind blemish on fruit, especially grapefruit, in the field.

Post-bloom fruit drop Description: C. acutatum infects petals and produces water-soaked lesions that eventually turn pink and then orange brown as the fungus sporulates. Infected fruitlets abscise at the base of the ovary, and the floral disk, calyx, and peduncle remain attached to the tree, forming structures commonly referred to as 'buttons'. Leaves surrounding an affected inflorescence are usually small, chlorotic, and twisted and have enlarged veins. Warm, wet weather favours disease development.

Lime anthracnose Description: It affects only Mexican lime. It attacks flowers, young leaves, young shoots and fruits. Infected fruitlets abscise, and 'buttons' are produced as in postbloom fruit drop. In severe cases, young leaves become totally blighted and drop, and shoot tips die-back, producing wither tip symptoms. The fruit lesions are often large and deep, and cause fruit distortion. The disease is favoured by warm, wet weather.

Rind blemish on fruit Description: The disease is caused by C. gloeosporioides. It is particularly severe on grapefruits. The blemish appears as a superficial, reddish brown discolouration, often in the form of tear stains, which usually appears following prolonged light rains in warm weather.

|

|

|

What to do:

|

|

Ants Certain ants are major indirect pests in citrus orchards. Although they do not damage the trees, they are associated to honeydew-producing insects such as soft scales, aphids, whiteflies, blackflies and mealybugs. Natural enemies often keep these insects under control; however, ants feeding on the honeydew give them indirect protection by disturbing natural enemies. As a result numbers of these honeydew producing insects, and indirectly other pests such as armoured scales, may rise to damaging levels.

Ant management does not imply eradication of all ants. There are many different types of ants in citrus orchards. Many of them are important predators of other insects, including pests of citrus. Some of the species that could be a problem due to their association with honeydew-producing insects (e.g. the big headed ant Pheidole megacephala and the pugnacious ant, Anoplolepis custodiens are also beneficial preying on a variety of insects, and are valuable predators on the ground. Therefore these ants should not be destroyed but kept off the trees.

|

|

|

What to do:

|

|

Citrus aphids (Toxoptera citridus and T. aurantii) They are small (1 to 3mm in length), brown to black in colour, and may be winged (having 2 pair of wings) or wingless. They feed by sucking on new growth and blossoms. High numbers are found on the leaf surfaces during the period of flushing (production of new shoots) and stems of attacked young shoots die back. Attacked leaves are curled and distorted. Flower buds are damaged or drop. Aphids excrete large amounts of honeydew. Leaves and fruits may turn black due to the growth of sooty mould. Symptoms can be severe on flush growth during dry periods following rainy spells. Citrus aphids transmit tristeza and other virus diseases in citrus. The black citrus aphid T. citridus is the most efficient vector of the citrus tristeza virus.

|

|

|

What to do:

|

|

Citrus blackflies (Aleurocanthus woglumi and A. spiniferus) Adults of the citrus blackflies resemble tiny (1.3 to1.7 mm in length) greyish moths. Eggs are usually laid in a spiral pattern on the lower surface of leaves. The immature stages are shiny black scale-like insects and are up to 1.2 mm in length. A white fringe of wax surrounds the body of older larvae and the pupae. The insects are most noticeable as groups of very small, black spiny lumps on leaf undersides. They produce a large amount of honeydew, which accumulate on leaves and stems and usually develop black sooty mould fungus, which cover the leaves blackening the foliage and sometimes the whole plant. Ants may be attracted by the honeydew. Heavy infestation causes general weakening and eventual death of plants due to sap loss and the development of sooty mould on leaves. Infested leaves may be distorted.

|

|

|

What to do:

|

|

Citrus bud mite (Aceria sheldoni) It is a tiny, worm-shaped, creamy white mite. It has only two pair of legs, and is hardly visibly without a magnifying glass. These mites occur in protected places such as under the bracts of buds. They attack the growing points of the twigs, causing malformation of the young leaves and flower buds. As a consequence, the growth of the trees is retarded. The fruit set can be seriously reduced and infested fruit may be malformed. Bud mites are more abundant during the hot season. Commonly found in developing and leaf buds. Damage under the bracts causes the death of the buds. Flower bud development is reduced, growth is retarded, branches become stunted and deformed, and rosette-shaped leaves are formed. The fruits, particularly in lemons are deformed. Almost all deformed fruits fall off at an early stage of development. Even light infestations may cause damage and control measures should be applied on time and regularly. Spots decrease the market value of the fruit and provide entry for fungal infection. Damage fruits loose moisture rapidly and do not keep well. Infestation on ripe fruits causes light yellow or silver discolouration. These mites attack all citrus species, but damage is usually worst in lemons. Damaged fruit could drop prematurely or assume abnormal shapes. The juice content of damaged fruit is significantly lower than that of normal fruit.

|

|

|

What to do:

|

|

The citrus rust mite (Phyllocoptruta oleivora) The yellow tiny citrus rust mite attacks mainly the fruit. Its feeding causes the rind of the fruit to turn silvery, reddish brown, or blackish. One result of mite damage is small fruit, which deteriorates rapidly. This damage lowers the market value of the fruit. Heavy populations of the rust mite cause bronzing of leaves and green twigs, and general loss of vitality of the whole tree. Warm and humid conditions favour the development of rust mite.

|

|

|

What to do:

|

|

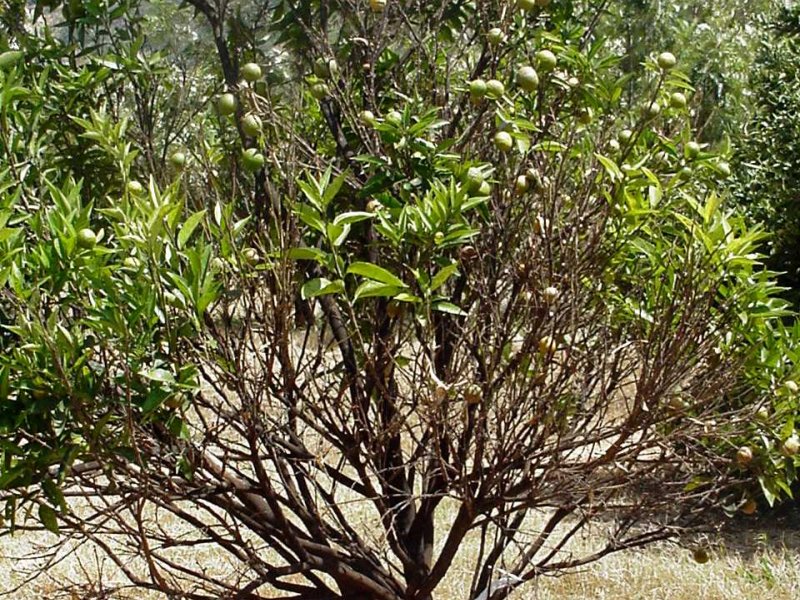

Citrus tristeza virus (CTV) CTV has been found in all citrus growing areas of the world. It is spread by infected propagative material and several species of aphids (Toxoptera citricidus, T. aurantii, Aphis gossypii, A. craccivora, A. spiraecola and Myzus persicae). T. citricidus is the most efficient vector of CTV. The virus has also been transmitted from plant to plant by the use of dodder (Cuscuta americana and C. subinclusa). CTV is not transmitted through citrus seeds. Most species of Citrus are hosts for CTV. The virus has naturally occurring field strains, which vary considerably in their ability to cause symptoms on different host plants and in the intensity of the symptoms expressed. Symptoms caused by these strains include: Seedling yellows (SY): This symptom consists of leaf yellowing and stunting in sour orange, grapefruit and lemon seedlings. This is a field problem when trees infected with SY strains of CTV are top-worked with grapefruit or lemon. Decline on sour orange: Sweet orange, grapefruit or tangerine scions on sour orange rootstock become dwarfed, yellow (chlorotic), and often die. The decline may occur over a period of several years or very rapidly (quick decline). Trees that decline slowly generally have a bulge (swelling) above the bud union, and honeycombing (many fine holes or pitting) is present on the inner face of bark flaps removed from the sour orange rootstock. When trees decline rapidly, honeycombing does not occur, but a brown line may be observed at the bud union after the bark is removed. When budwood infected with decline-inducing strains is propagated on sour orange seedlings, the trees produced are stunted and unthrifty. Stem-pitting on limes, grapefruit and sweet orange. Severely affected trees are stunted and may have bushy appearance. Leaves are yellow, and the twigs are brittle and break easily when bent. When the bark is removed from the affected twigs, elongated pits are seen in the wood. Trees affected by stem pitting have reduced yield and fruit quality is poor. Some strains cause longitudinal pits in the trunk, resulting in ropey appearance, and when bark is removed from the depressed parts deep pits can be seen in the wood.

|

|

|

What to do:

|

|

Damping-off (Rhizoctoni solani) and Phytophthora spp. Damping-off of citrus is most often caused by Rhizoctonia solanispp. Phytophthora spp. The typical symptom of damping-off is dying of seedlings just after emergence from the soil. However, damping-off fungi can also cause seed rot, resulting in sparse stands of seedlings in nursery beds.

|

|

|

What to do:

|

|

False codling moth (Cryptophlebia leucotreta) It is small (wingspan of 16-20 mm), dark brown to grey in colour. The moths are active at night. Female moths lay single eggs on ripening citrus fruits. The young caterpillar mines just beneath the surface, or bores into the pith causing premature ripening of the fruit and fruit drop. The initial symptom on the fruit is a yellowish round spot with a tiny dark centre where the insect entered the fruit. In a later stage brown patches appear on the skin, usually with a hole in the centre. The young caterpillar is creamy-white with a dark brownish head. With age the body turn pinkish red. The fully-grown caterpillar is 15 to 20 mm in length. When mature the caterpillar leaves the fruit and pupates in the soil or beneath surface debris. Navel oranges seem to be the most heavily attacked. Grapefruit is less susceptible. In lemons and limes larval development is rarely, if ever, completed.

|

|

|

What to do:

|

|

Fruit flies (Bactrocera invadens, Ceratitis capitata and C. rosa) Several species of fruit flies are pests of citrus in Africa. In East Africa the most important are B. invadens, a new species of fruit fly recently introduced in the region, and C. capitata (Sunday Ekesi, personal communication). The female fly lays eggs within the skin of ripening fruits. Spots develop on the skin where eggs were laid and the hatching larva enters the fruit. The attacked area becomes soft, turns brown and decays as a result of secondary infection.

|

|

|

What to do:

|

|

Greening disease It is caused by a bacterium (Candidatus Liberibacter africanus). The disease is transmitted by citrus psyllids (Trioza erytreae) and through use of budwood obtained from diseased trees. The disease is not soil-borne. It is not seed-borne and it is not mechanically transmitted. In Kenya, the disease is not found below 800 m above sea level because both the bacterium causing the disease and citrus psyllids are sensitive to high temperatures. Optimum temperature for symptom expression is 21 to 24 degC; symptoms are masked above 26 degC. The disease is especially destructive to sweet oranges and mandarins. It is less severe on lemon, grapefruit, citron and West Indian lime. Symptoms on the leaves show mottling, yellowing of veins or zinc defiency (i.e. small leaves, interveinal chlorosis and brush-like growth). Zinc deficiency induced by greening is confined to one or several branches within a tree (sectoral infection). Trees infected by greening are distributed within the orchard randomly. Affected branches bear few fruits and in some cases do not fruit. The affected fruits are usually under-developed, reduced in size, lopsided, start to colour from the stem end instead of the stylar end as in the case with healthy fruits. Affected fruits drop prematurely. In seedy citrus varieties, seed abortion occurs. Severely diseased trees exhibit open growth, sparse chlorotic foliage, dieback of branches and severe fruit drop. Rootstocks have no effect on greening disease.

|

|

|

What to do:

|

|

Citrus leafminer (Phyllocnistis citrella) The caterpillar of the citrus leafminer usually attacks young leaves and shoots. It mines the undersurface of young leaves, but it can attack both leaf surfaces, in heavy infestations, and occasionally the fruit. Its feeding causes serpentine mines that have a silvery appearance and reach a length of 5 to 10 cm. The middle of the mines is marked by a light or a dark coloured stripe, which consists of the excreta of the caterpillars. The caterpillars are greenish yellowish and are to 4 mm in length. Caterpillars pupate within the mine, near the leaf margin, under a slight curl of the leaf. The moths are tiny (2 to 3 mm long), greyish white in colour with fringed wings. Eggs look like small dew drops and are usually laid on the underside of the leaves. Attacked young leaves are twisted, show brown patches of dead tissue and eventually fall off. Heavy infestations can interfere with photosynthesis because of the reduction in leaf surface. This pest is especially troublesome in citrus nurseries. It can kill young nursery plants. This leafminer was a frequently observed pest during a survey of major citrus pests conducted in Kenya, Malawi, Uganda, Tanzania and Zambia in 1995 (B. Löhr, personal communication). |

|

|

What to do:

|

|

Mealybugs Several species of mealybugs attack citrus. They suck sap from tender leaves, petioles and fruit. Feeding on the fruit results in discoloured, bumpy, and scarred fruit, with low market value, or unacceptable for the fresh fruit market. Mealybugs excrete honeydew, which leads to the growth of sooty mould on fruit and leaves. Fruit cover with sooty mould at harvest must be washed. The most important is the citrus mealybug (Planoccous citri).

|

|

|

What to do:

|

|

Phaeoramularia fruit and leaf spot The disease is caused by fungus Phaeoramularia angolensis. The disease is favoured by wet, cool conditions. On leaves, the fungus produces circular, mostly solitary (single) spots that are up to 10 mm in diameter with light brown or greyish centres. Each spot is usually surrounded by a yellow halo. Occasionally, the thin necrotic tissue in the centres of old spots falls out, creating a shot-hole effect. During rains, leaf spots on young leaves often join together ending in generalised chlorosis. Premature defoliation takes place when leaf petioles are infected. On fruit, the spots are circular to irregular in shape or joining together and surrounded by yellow halos. Most spots measure up to 8 mm in diameter. On young fruits, symptoms often start with nipple-like swellings without yellow halos.

Spots on mature fruits are normally flat, and often a dark brown to black sunken margin similar to anthracnose around the spots is observed. Fruits of more than 40 mm in diameter are somehow resistant to the disease. The disease has been observed on all citrus species including grapefruit, lemon, lime, mandarin, pummelo and orange. Grapefruit, mandarin, pummelo and orange are very susceptible. Lemon is less susceptible and lime is least susceptible. The disease can reduce yield by 50 to 100%.

|

|

|

What to do:

|

|

Phytophthora-induced diseases (Phytophthora spp.) They cause the most serious soil-borne diseases of citrus. These fungi are worldwide in distribution and cause citrus production losses in irrigated, arid areas as well as in areas with high rainfall. Diseases caused by Phytophthora spp. include damping-off in seedbeds, gummosis and brown rot of fruits. The most widespread and important Phytophthora spp. are P. nicotianae and P. citrophthora. Others of lesser importance in the tropics are P. citricola, P. hibernalisand P. palmivora. The most serious disease caused by Phytophthora spp. is gummosis (also known as foot rot). Gummosis: An early symptom of gummosis is gum oozing from small cracks in the infected bark around the bud-union giving the affected trees a bleeding appearance. Citrus gum, which is water soluble, disappears after heavy rains. Severely affected tress have yellow foliage that eventually drops and twigs die-back often with a crop of small-sized fruits still hanging from bare branches. The feeder roots are destroyed when the root cortex is attacked; turn soft and easily separate giving the root system a stringy appearance. In an advanced stage, the trunk becomes girdled (encircled) and the affected trees decline and eventually die. Gummosis is favoured by high moisture in the soil. Infection of fruit by Phytophthora spp. produces brown rot. The affected area is light brown, leathery and not sunken compared with the adjacent rind. Under humid conditions, white fungal growth (mycelium) forms on the rind surface. In the orchard, fruits on or near the ground become infected when they are splashed with water or come in contact with soil that is infested by Phytophthora spp. Most of the infected fruits drop, but those that are harvested may not show symptoms until after they have been held in storage for a few days. Brown rot epidemics are usually restricted to areas where rainfall coincides with early stages of fruit maturity. It is important to note that most Phytophthora spp. are seed-borne.

|

|

|

What to do:

|

|

Red fire ants or weaver ants (Oecophylla longinoda) A particular case is that of the red fire ants or weaver ants which nest on citrus and other fruit trees (guava, soursop, cashewnuts, coconut palms among others). These ants are present in many countries in Africa. They are common in the coastal regions in East Africa. They built nests on trees by joining leaves with silk produced by the larvae. These ants are very active moving on the trees and on the ground in search of food. They are highly voracious feeding on a large range of insects visiting the trees, and are important in controlling many insect pests in fruit trees and coconut palms. In spite of these benefits, weaver ants are considered by some as a pest due to their aggressiveness combined with painful bites, which makes fruit picking difficult, and to their association with honeydew-producing insects. They can foster the build-up of these insect pests, but it has been observed that they do kill some of them when the amount of honeydew produced by these insects is bigger than the amount required by the colony of weaver ants.

The benefits provided by predatory ants feeding or deterring insect pests must be outweighed against the damage they may cost indirectly. As a whole weaver ants are considered beneficial. They have been used actively in China for the control of citrus pests for centuries (Way and Khoo, 1992). Experienced farmers in Asia and Africa have developed their own methods to deal with the inconvenience of weaver ants during harvesting.

|

|

|

What to do:

|

|

Nematodes More than 40 nematode species have been associated with citrus worldwide. The economically important species are the citrus nematode (Tylenchulus semipenetrans) and the burrowing nematode (Radopholus similis).

1) The citrus nematode (T. semipenetrans) It causes a slow decline of citrus trees. Affected trees show reduced vigour, small yellow leaves, defoliation, die-back of twigs, and small fruits. The citrus nematodes are ectoparasitic and sedentary. Only females are parasitic on roots. They are found on the surface of fibrous roots under debris-covered egg masses embedded in a gelatinous matrix. The life cycle, from egg to egg, is completed within 6-8 weeks at temperatures of 24-26°C. Optimal reproduction occurs at 28-31°C. Soil salinity increases the population density of citrus nematode. In affected orchards, populations of the nematode are concentrated in upper soil layers. Movement of plant material and soil is responsible for the spread of the nematode. Also agricultural implements and water (irrigation or rain) spread the nematode in a citrus orchard.

2) The "burrowing nematode" (Radopholus similis) It is called "burrowing nematode" on account of the cavities and tunnels it produces in the root tissues. Symptoms are generally present on groups of trees that increase in number with time, hence, the name, spreading decline. Symptoms are much more severe than in the case of T. semipenetrans and the spread is much quicker. Affected trees show fewer and smaller leaves and an abundance of dead twigs and branches. Trees wilt during periods of lack of moisture but generally the trees are not killed. It is an endoparasitic and migratory. Two distinct races of the nematode are known: the banana and citrus race. The former is known to attack banana roots but not citrus. The citrus race attacks bananas and citrus. The life cycle requires 18-21 days at 24-26°C, the optimum temperature being 24°C. Burrowing nematodes migrate through roots and from root to root to feed. The nematodes are rarely found in the top 10 cm of the soil, highest populations being between 30 and 180 cm. Primary spread is thorough propagating infested seedlings.

|

|

|

What to do:

|

|

Scales

Scales are small insects (1.0 to 7 mm long), which resemble shells glued to the plant. There are many species (types) of scales on citrus, which vary in shape (round to oval) and colour according to the species.

There are two main groups: hard (armoured) and soft (naked). The armoured scales are the most serious pests. The most important armoured scales attacking citrus are the red scale (Aonidiella aurantii), the mussel purple scale (Lepidosaphes beckii), and the circular scale (Chrysomphalus aonidum). The most important soft scales are the soft brown scale (Coccus hesperidum) and the soft green scale (Coccus viridiis or C. alpinus).

Female scales have neither wings nor legs. Females lay eggs under their scale. Some species give birth to young scales directly. Once hatched, the tiny scales, known as crawlers, emerge from under the protective scale. They move in search of a feeding site and do not move afterwards. They suck sap on all plant parts above the ground. Their feeding may cause yellowing of leaves followed by leaf drop, poor growth, dieback of branches, fruit drop, and blemishes on fruits. Leaves may dry when heavily infested, and young trees may die.

Soft scales excrete honeydew, causing growth of sooty mould. In heavy infestations fruits and leaves are heavily coated with sooty mould turning black. Heavy coating with sooty mould reduces photosynthesis. Fruits contaminated with sooty mould loose market value. Ants are usually associated with soft scales. They feed on the honeydew excreted by soft scales, preventing a build-up in sooty moulds, but also protecting the scales from natural enemies. Armoured scales do not excrete honeydew. |

|

|

What to do:

|

|

Swallowtail butterfly (Papilio demodocus) The caterpillars of the swallowtail butterfly are also known as "orange dog". The butterfly is black with yellow markings on the wings, and has a wingspan of about 10 cm. They are common during the rainy season. Female butterflies lay whitish, grey eggs mainly on the tender terminal twigs and leaves. The caterpillars are white-brown, or green in colour. Most spines disappear as the caterpillar grows. Young caterpillars are brownish with white patches and are spiny. They resemble fresh bird droppings. Older caterpillars are green with some light markings and two eye-like spots at both sides of the front part of the body. When disturbed caterpillars shoot out a fleshy, forked retractable organ, through a slit behind the head, which gives off a repulsive smell.

Fully grown caterpillars are about 5 cm long. Caterpillars feed specially on the new growth of citrus trees. They can cause extensive damage to young trees, especially in citrus nurseries where their feeding can cause complete defoliation of the plant.

|

|

|

What to do:

|

|

Termites Different species of termites damage cassava stems and roots. Termites damage cassava planted late or in the dry season, in particular when the crop is still young at the peak of the dry season. They chew and eat stem cuttings which grow poorly, die and rot. The may destroy whole plantations. In older cassava plants termites chew and enter the stems. This weakens the stems and causes them to break easily.

|

|

|

What to do:

|

|

Citrus thrips (Scirtothrips aurantii) Citrus thrips are tiny insects (0.7 to 1 mm in length), and orange yellow in colour. Young stages are wingless, but adults have 2 pairs of narrow wings. Damage is caused by larvae and adults feeding on young twigs, leaves and fruits. Thrips feeding produces brown blemishes on the rind. Typical damage is the presence of rings of brown russet marks around the stem of the fruit. The damage is cosmetic and does not affect eating quality. However, external fruit blemishes can be so severe that the fruits are unmarketable. New shoots can be severely damaged. If thrips are abundant on young twigs, their feeding causes deformation of the twigs, which become thickened and distorted. In severe infestations, the leaves are deformed; young leaves are underdeveloped and drop when touched.

|

|

|

What to do:

|

|

Citrus woolly whitefly (Aleurothrixus floccosus) The citrus woolly whitefly was reported for the first time in East and Central Africa in the early to mid 90s. Serious attacks on citrus were observed in Kenya, Malawi, Tanzania and Uganda. The adults of this whitefly resemble small white moths, covered with mealy white wax. Eggs are laid on the lower surface of young leaves. The young stages resemble soft scale insects and have a woolly appearance. They produce large quantity of honeydew that leads to the growth of sooty mould on the infested trees. This may cause defoliation, loss of fruits and dwarfing of trees. Small, mottled fruits are produced. |

|

|

What to do:

|

Geographical Distribution in Africa

Geographical Distribution of Citrus in Africa. Updated on 8 July 2019. Source FAOSTAT.

© OpenStreetMap contributors, © OpenMapTiles, GBIF.

Read more

Angola: Laranjeira (Portuguese) (C. sinensis); Limoeiro (Angola); Limeira (Portuguese) (C. aurantifolia) (Bossard, 1996); Elimau (Umbundu), Limao (Portuguese) (Citrus limon (L.) (Bossard, et al.,1996); Tangerineira (Portuguese) (C. reticulata) (Lautenschläger et al., 2018).

Benin: Azongbo (Fon) (C. sinensis) (Dougnon et al., 2018); Wountchi Wouli (Adja); Klé (Fon, Goun); Ossan (Yoruba); N'tisiti (Gèn) (C. aurantifolia) (Adjanohoun, 1989). Clédo (Fon); Ntissiti (Mina); Citronnier, Limon (French); Yovozin, Gbodokle, Kletin (Fon); Osanorombo (Yoruba) (C. limon (L) (Koné et al., 2019).

Burundi: Indimu (Kirundi) (C. limon (L.) (Koné et al., 2019).

Burkina Faso: Lemburu (Sanan) (C. aurantifolia) (Zerbo et al., 2011).

Cameroon: Orange (Fundong) (C. sinensis) (Focho et al., 2009); Ofumbi Beti (Sangmelima, Yaounde); Meke (Bamileke) (C. aurantifolia); Grape (Fundong); Citron (local French); Ofumbi Beti (Ewondo); Nyopiang (Ngumba) (C. limon (L.) (Koné et al., 2019).

DRC; Lala Dinzenzo, Didiya (Kikongo) (C. sinensis); Malimbungo (Boko); Malinboungo (Tsaangui) (C. aurantifolia); Malala (Kiyanzi); Lala Dia Nsa (Kikongo); Zidolo (Ngwaka); Lilala (Lonkundo); Bolala (Kisengele, Kinunu); Ndimu (Swahili), Kpetape (Ngbandi) (C. limon (L.) (Koné et al., 2019).

Ethiopia; Arbo; Komtatie (Amharic); Qolaa Burtukanaa (Afaan Oromoo); Brtukan (Tigrigna); Lomy (Amharic) (C. sinensis); Lommii (Afaan Oromoo) (C. aurantifolia) (Karunamoorthi & Hailu, 2014).; Lemin (Tigrigna); Lomae (Gedeoffa); Loomii (Afaan Oromo) (C. limon (L.) (Koné et al., 2019).

Egypt: laymun (C. limon (L.) (Koné et al., 2019).

Gabon: Lemon (Fang); Citronnier (French) (C. aurantifolia)

Ghana: Ankaa (Twi dialect) (C. sinensis); Abonua (Adangbe); Ankaa twadee (Twi dialect) (C. aurantifolia); Nkagyua (C. limon (L.) (Koné et al., 2019).

Guinea Bissau: Limon (Guinean Creole); Mandabannebéne (Nalu); N’sinim nelbéne (Nalu) (C. limon (L.) (Catarino et al., 2016)

Guinea Conakry: Lemunukumum (C. limon (L.) (Koné et al., 2019).

Ivory Coast: Citronnier (C. limon (L.) (Koné et al., 2019).

Kenya; Mudimu (Giryama); Machunga (Luo); Lichunga (Suba) (C. sinensis); Kitimo (Kamba); Mûtimû (Kikuyu); Ndim (Luo); Endim (Suba) (C. limon (L.) (Koné et al., 2019).

Madagascar: Matsioka; Voahangy Ala (Betsimisaraka) (C. sinensis); Sôhafoe, Tsôhamatsiko (Antakarana); Citronnier, Tsoha-Adiro, Vasary Makirana (Malgache); Citronnier, Citron Vert (French) (C. aurantifolia) (Nicolas, 2012): Tsaobiloha (Antakarana); Tsoha-Adiro, Voasary Makirana (Malgache); Citron, Citron Jaune (French); voahangitsoha (Betsimisaraka) (C. limon (L.); Mandarinina (Betsimisaraka) (C. reticulata) (Rakotoarivelo et al., 2015).

Mali: Lemourou-Koumouni (Bambara); Lemouroucoumouni (Malinke) (C. aurantifolia): Lemuru ba (Bambara) (C. limon (L.); Lemuru kumu (Bambara) (Koné et al., 2019).

Mauritius: Bigarade; Oranger (Creole); Narten (Tamoul) (C. sinensis); Limon (Rodrigues Creole) (C. limon (L.) (Koné et al., 2019).

Mozambique: Muraranji (Chindau) (C. sinensis) (Bruschi et al., 2011).

Niger: Lemu tsami (Hausa); Lemu (Zarma) (Saadou, 1993).

Nigeria: Osan Paya (Yoruba); Oroma-Nkeresi (Igbo); Lemu Yamiku (Hausa); Anumei (Esan) (C. sinensis) (Aiyeloja & Bello, 2006); Mkpiri Osokoro (Ibibio); Osan wewe (Yoruba); Lemu (Hausa), Oroma-nkirisi (Igbo), Alimo-ebo (Efik) (C. aurantifolia) (Iyamah & Idu, 2015).; Itie-akpaenfi (local dialect); Alimo-negieghe (Efik) (C. limon (L.) (Koné et al., 2019).

Rwanda: Indumu (C. limon (L.)

Sierra Leone: Lem (Krio); Dumbele (Mende); Ma roks (Temne) (C. aurantifolia) (Koné et al., 2019).

Senegal: Limon (Niominka); Lemon, Limon (Wolof, Sérer, Peul, Toucouleur, Niominka); Limono; (Manding); Bulem Mugna; (Diola); Kitoni; (Baïnouk); Citronnier, Lime, Limettier Acide, Citron Vert (Français Local) (C. aurantifolia); Gulemin (Diola) (C. limon (L.) (Koné et al., 2019).

South Africa: Lorenji (Isi Xhosa) (C. sinensis); Tshikavhavhe (Luvenda); Ulamula, Lamuni (Xhosa); Tshikavhavhe (Vhavenda); Moswiri (Pedi) (C. limon (L.) (Koné et al., 2019).

Tanzania: Mndimu (Swahili) (C. aurantifolia); Mlimau (C. limon (L.)

Togo: Mutivuyu (Akposso), Citronnier (French); Dontiti (eve), Ntiviti (Ouatchi); Ntisi (Mina); Yorozinkle (Fon); Ossan orombo (Yoruba); Akanka (Tem) (C. aurantifolia) (Tchacondo et al., 2011).).

Uganda: Muchungwa (Luganda) (C. sinensis); Endimo (Rutooro); Nimawa (Luganda) Eniimu (C. limon (L.) (Koné et al., 2019).

Zimbabwe: Mulemoni (Shona) (C. limon (L.) (Koné et al., 2019).

Zambia: Lemoni (C. limon (L.) (Koné et al., 2019).

General Information and Agronomic practices

Introduction

Citrus is a genus of flowering plants that belongs to the family Rutaceae (citrus family). The genus comprises approximately 16 species, with several hybrids and cultivars developed over time to meet varying consumer preferences. Some of the economically significant species within the genus include well-known fruits including orange (Citrus x sinensis), lemon (Citrus x limon), grapefruit (Citrus x paradisi), lime (Citrus x aurantifolia) and Mandarins (C. reticulata).

© Maundu, 2005

© A Bekele-Tesemma.

Citrus spp. are natives of the subtropical and tropical regions of Asia and the Malay Archipelago. They have been cultivated since ancient times, and spread to other regions of the world, including the Mediterranean, South America and southern states of USA such as California and Florida, where suitable soil and climatical conditions exist. The citrus growing belt follows the equator, extending either side of it about 35 North and 350 South latitude. It embraces tropical, subtropical and the intermediate zones.

Citrus fruits are predominantly consumed as fresh fruits due to their pleasant flavor, juiciness, and high vitamin C content. They are widely used in culinary preparations, such as salads, juices, desserts, and beverages. Citrus fruits have a reputation for their medicinal properties, primarily attributed to their vitamin C content and antioxidant properties. They are believed to boost the immune system and promote overall well-being. Citrus fruits and their peels are used in traditional medicine for various purposes, such as treating colds, indigestion, and skin conditions.

Apart from their culinary and medicinal applications, citrus fruits find use in various industries. The essential oils extracted from citrus peels are valuable in the perfume, cosmetics, and flavoring industries. Additionally, some species of citrus trees are cultivated for ornamental purposes in gardens and landscapes. Among the common species, oranges (Citrus sinensis) are particularly noteworthy for their high nutritional value. They are an excellent source of vitamin C, providing more than the recommended daily intake in just one fruit. Oranges also contain dietary fiber, vitamin A, potassium, and various antioxidants, making them a wholesome and nutritious addition to one's diet.

The citrus industry is a substantial contributor to the global agricultural economy. Various processed products like orange juice, lemonade, and grapefruit extracts are widely available in the market. The essential oils extracted from citrus peels are used in cosmetics, aromatherapy, and food flavorings. Key producers in the citrus market include countries like Brazil, the United States, China, and Spain, which export significant quantities of citrus fruits and products to meet global demand

(Orwa C, et al., 2009, Tran G., 2016, plantvillage (n.d)).

Species account

Species and common names

i. Founder species

1. Citrus reticulata - Mandarin, Mandarin orange (English); Chenza (Swahili)

The mandarin orange also mandarin or mandarine, (Citrus reticulata), is a small tree originally from southern Asia and the Philippines. It is one of the original citrus species that through breeding and natural hybridization have given rise to the many commercial varieties we see. With the citron and pomelo, it is the ancestor of the most commercially important hybrids (such as sweet and sour oranges, grapefruit, and many lemons and limes). Tangerines are hybrids of mandarins mainly of mandarin with pomelo and usually have traits of mandarin but less pronounced.

C. reticulata is a low woody shrub, evergreen tree that typically grows to a height of 3 to 8 m. Fruits are small, oblate, (flat top and bottom and wide in the middle), typically bright orange when ripe with a thin, easily peelable skin and distinctive sections, giving it the name "reticulata," which means "net-like." Flesh is easy to split into segments. In tangerines the fruits tend to be more spherical.

Mandarin and related tangerine hybrids are grown in tropical and subtropical areas. They however do better in colder climate.

Many cultivated varieties of mandarins are seedless or have few seeds, making them more enjoyable to eat without the inconvenience of spitting out seeds.

(Thulaja, N. R, 2005; Bekele-Tesemma, A. et al., 1993; Orwa C, et al., 2009, PFAF Plant Database. (n.d.), plantvillage (n.d)).

© Azene Bekele-Tesemma

@Maundu 2005

Pixie mandarin (Pixie orange).

Pixie is a mandarin variety propagated mainly through grafting. The trees can grow to 4 or 5 meters. Fruit: small to medium-small, usually globose to slightly oblate, and sometimes has a neck. The rind is yellow-orange, medium-thin, and not as easy to peel as tangerine. The flesh is often seedless or with one seed, orange colored, and juicy.

Pixie is the result of an open pollination of two mandarin varieties- King and Dancy (named Kincy) that took place in 1927 at the University of California Citrus Research Center, Riverside and eventually released in 1965. Pixies are a recent introduction into Kenyan farms and markets. They are generally sweeter than oranges, juicier and with more superior flavor. Pixie orange farming in Kenya is mainly concentrated in Makueni and Kitui Counties. The demand is growing within the country and currently supplies cannot meet the growing demand and hence they are more expensive than oranges.

For further reading see:

• https://citrusvariety.ucr.edu/crc3568#:~:text=Parentage%2Forigins,and%20eventually%20released%20in%201965.

• https://aggie-hort.tamu.edu/citrus/mandarins.html

2. Citrus maxima - Pomelo

The pomelo, Citrus maxima, is the largest citrus fruit, and the principal ancestor of the grapefruit. It is considered one of the three original species, with mandarin and citron, of the genus Citrus. It is therefore a natural, non-hybrid, citrus fruit, native to Southeast Asia. The pomelo is a small to medium sized tree to 10 meters or more. Leaves are large with winged petioles. The flowers white, cream to yellow.

The fruit is large, to 25 cm in diameter, and may weigh up to 2 kg. It has a thicker rind than a grapefruit. The flesh tastes like mild grapefruit, with a little of its common bitterness. The fruit generally contains a few, relatively large seeds, but some varieties have numerous seeds.

3. Citrus medica L. - Citron

The citron (Citrus medica) is a small evergreen, rather bushy spiny tree which has been cultivated since ancient times in India and much of South Asia. Together with pomelo and mandarin, citron is one of the primary species (parents) of the commercial Citrus fruits. From these, other citrus hybrids have developed either through natural or artificial hybridization. Hybrids of citrons with other citrus include lemons and many of the limes.

Flowers: Purple to white or cream. Fruit: Large to 15 cm long, oblong (long oval, protuberant at the tip, green on the outside when unripe to lemon yellow when ripe, fragrant. Fruit resembling the lemon but much larger with a thick tough skin, rough on the surface. Flesh is firm, pale yellow to white, rather dry, slightly sour to slightly sweet with many seeds.

The thick peel makes up nearly three quarters of the fruit volume. It is the most useful part of the fruit in South Asia being used in traditional medicines, perfume manufacture, and religious purposes. It is made in to candies and it is also a source of a type of oil used as a flavoring in sweets and beverages. The pulp is mainly used as a source of other products.

Cultivated a lot in South Asia, West Indies, South and Central America and the Mediterranean region. In Africa, citron is more common in West Africa but also found in much of tropical Africa.

Source: Various. See also: http://birds.songs.free.fr/papedas.html

ii. Hybrids

4. Citrus × aurantium Sweet Orange Group (Synonyms: Citrus sinensis, Citrus × aurantium var. sinensis).

Common names: Orange, Sweet orange, Navel Orange, Valencia Orange (English); Chungwa (Swahili); Oranger doux (French)

Sweet orange - Citrus x sinensis is believed to have originated in Southeast Asia, specifically in the region encompassing northeastern India, Myanmar, and southwestern China. However, it is now cultivated in various parts of the world with suitable climates for citrus growth.

Orange trees are evergreen and reach heights of 6 to 15 m and can live for over a century. Most plantations have an economic lifespan of around 30 years. Leaves: glossy, dark green leaves, elliptical or oval in shape, alternately arranged on the branches. The leaves have narrowly winged petioles, a feature that distinguishes it from bitter orange, which has broadly winged petioles Flowers: white, fragrant aroma. Fruit: rather variable in color and shape, with a thick, orange-colored rind (peel) that encloses the juicy segments within. The pulp is typically divided into easily separable segments, and the fruit contains several seeds.

Orange is a widely cultivated fruit with delicious and refreshing qualities. It is consumed fresh, processed into various products, and used in salads, desserts, and beverages. Sweet orange juice is a popular and nutritious global drink. The peels are used for zest or essential oil extraction in perfume, flavoring, and cosmetic industries (Orwa C, et al., 2009, Bekele-Tesemma, A. et al., 1993, plantvillage (n.d)).

© A Bekele-Tesemma.

© A Bekele-Tesemma

© Maundu 2005

@Maundu, 2005

© Maundu, 2005

© Maundu, 2005

Washington navel oranges are native to Brazil where a single orange was discovered growing as a mutation or bud-sport in 1820. Washington navel orange trees have a round, somewhat drooping canopy. The flowers lack viable pollen so the Washington navel orange will not pollinate other citrus trees. Because of the lack of functional pollen and viable ovules, the Washington navel orange produces seedless fruits. These large round fruits have a slightly pebbled orange rind that is easily peeled, and the navel, really a small secondary fruit, sometimes protrudes from the apex of the fruit.

© Maundu, 2005

© Maundu, 2005

For further reading see: https://citrusvariety.ucr.edu/crc1241A#:~:text=Parentage%2Forigins,tree%20in%20the%20early%201800s.

5. Citrus × aurantium Grapefruit Group (Synonyms: Citrus × aurantium var. paradisi, Citrus paradisi)

Common names: Grapefruit (English); Balungi (Swahili).

Citrus x paradisi (Citrus × aurantium Grapefruit Group) commonly known as Grapefruit is believed to be an interspecific hybrid of two citrus species: sweet orange (Citrus sinensis) and pomelo (Citrus maxima). It was first discovered in the 18th century on the Caribbean island of Barbados (West Indies). Grapefruit is now grown in various regions with tropics and the warmer subtropics.

Grapefruit trees are medium-sized evergreen trees that can grow to a height of 5 to 6 m. Leaves: glossy and dark green. Flowers: are white and pleasantly fragrant. Fruit: is typically round or slightly oblate, and the peel color ranges from pale yellow to pink or red, depending on the variety.

Grapefruit is commonly consumed fresh, and its juicy, tangy, and slightly bitter flavor makes it a popular breakfast fruit. It is also used in salads, juices, smoothies, and cocktails. Grapefruit comes in different varieties, including white, pink, and red (also known as Ruby Red). The flesh color can vary depending on the variety, with the red varieties being sweeter and more colorful.

Grapefruit is a good source of vitamins and minerals, particularly vitamin C, potassium, and dietary fiber. Grapefruit is known for its potential health benefits, including aiding digestion, supporting the immune system, and promoting heart health. Seed extract, derived from the seeds and pulp of the fruit, is sometimes used as a natural antimicrobial agent in alternative medicine. Unlike some other citrus species, grapefruit is less commonly used for producing essential oils or as a rootstock for grafting other citrus varieties because yields on this stock are low.

(PROSEA, 2016, Orwa C, et al., 2009, plantvillage (n.d)

© Maundu, 2005

©Maundu et al. 2005

6. Citrus x aurantifolia

Common names: Lime, Key lime, Acid lime (English); Ndimu (Swahili)

Citrus x aurantifolia is a small, evergreen tree that typically grows to a height of 3 to 4.5 m with thorny branches and glossy. Leaves; Oval, rather small, shiny green 4–8 cm, the leaf stalk with a narrow “wing”, an extra leafy growth and a “joint” with the leaf blade, edge smooth or round-toothed. Flowers; Both buds and flowers white. Fruits: oval, a thin, smooth, yellow-green rind that turns yellow when fully ripe. The flesh is juicy, acidic, and highly aromatic, filled with small seeds. Lime is widely used in cooking and medicine due to its highly acidic juice. It is a popular ingredient in cuisines worldwide, especially in desserts like Key lime pie, sauces, marinades, and beverages. The fruit's rind contains aromatic oils used in perfumes, cosmetics, and cleaning products. Lime trees are also grown for their attractive foliage and fragrant flowers, serving as ornamental plants.

(Bekele-Tesemma, A. et al., 1993, Orwa C, et al., 2009, plantvillage (n.d).

7. Citrus × limon (Syn: Citrus limon)-

Common names: Lemon (English); Limau (Swahili)

Lemon - Citrus x limon is thought to be a hybrid between the citron (Citrus medica) and the sour orange (Citrus × aurantium). Presumably native to southern Asia, now widely cultivated in all subtropics and occasionally in the tropics. Its adaptability to diverse environments has contributed to its widespread presence in tropical, subtropical, and some temperate regions.

Lemon trees are small to medium-sized evergreen trees, typically reaching a height of 3 to 6 m with stout stiff spines. Leaves: are glossy green. Flowers: fragrant, white with a hint of purple. Fruits: generally, round or oval, with a bright yellow rind that contains essential oils giving them their distinct aroma. Lemons are a fundamental ingredient in various cuisines and culinary applications. Their tangy and refreshing flavor enhances dishes, desserts, and beverages. Lemon juice is a popular natural acidifier, preservative, and flavor enhancer used in cooking, baking, and making refreshing lemonades.

Lemons also have numerous non-culinary uses. They are a rich source of vitamin C, known for its immune-boosting properties. Lemon essential oil, extracted from the peel, is used in aromatherapy for its invigorating scent. The citric acid found in lemons makes them a natural cleaning agent, effectively removing stains and odors.

Lemons are valued for their versatility, tangy taste, and high citric acid content. They stand out for their widespread use in both culinary and non-culinary applications, making them a staple in households, restaurants, and industries alike

(PROSEA, 2016, Orwa C, et al., 2009, plantvillage (n.d)).

© Maundu 2005

© Maundu, 2005

8. Rough lemon (Citrus x jambhiri Lush.) also Rough skin lemon is one of the most vigorous rootstocks used with citrus, under favorable conditions producing a very large tree, and has seen widespread use around the world. It reproduces true from seeds. Rough lemon is believed to have originated in northern India where it grows wild. It is naturalized in the West Indies and Florida. Rough lemon is believed to be a cross between a mandarin and a citron. The fruit can be used at any stage of ripeness and is often made into juices.

It is a tree of medium size and thorny; Fruit oblate, rounded or oval; base flat to distinctly necked; apex rounded with a more or less sunken nipple of medium size; peel lemon-yellow to orange-yellow, rough and irregular, with large oil glands.

Ⓒ Adeka, 2005

Ⓒ Maundu, 2015

Source: Various. See: http://citruspages.free.fr/lemons.php

9. Citrus × aurantium var. clementine

Common name: Clementine

Citrus varieties of commercial importance include the following:

- Oranges: 'Washington Navel' (alt: 1000-1800 m above sea level), 'Valencia Late', 'Hamlin' and 'Pineapple' (all alt from 0 - 1500 m above sea level)

- Mandarins: 'Kara', 'Satsuma' (0-1500 m above sea level), 'Clementine', 'Dancy' (0-1800 m above sea level), 'Pixie', 'Encore' and 'Kinnow'

- Tango/ Tangelo (hybrids of mandarins): 'Temple' a Tango (mandarin x orange) and 'Minneola' a Tangelo (mandarin x grapefruit)

- Grapefruit: 'Marsh Seedless', 'Duncan' and 'Ruby Red', 'Red Blush' (0-1500 m above sea level) and 'Thomson' (1000-1500 m above sea level)

- Lemons: 'Meyer', 'Eureka', 'Lisbon' and 'Villa Franca' (1000-1500 m above sea level), Rough lemon (0-1500 m)

- Limes: 'Mexican', 'Tahiti' and 'Bears' (0-1500 m)

Note: All varieties mentioned are available in Kenya, particularly in Kenya prison farms, albeit their commercial availability is a problem due to citrus greening disease, which is prevalent in Kenya in all areas above 900 m altitude. Since there is no citrus certification scheme in Kenya, there is no assurance that planting material derived from any Kenyan nursery is greening disease-free.

Ecological information

Citrus species can thrive in a wide range of soil and climatic conditions. Citrus is grown from sea level up to an altitude of 2100 m but for optimal growth a temperature ranges from 2deg to 30deg C is ideal. Long periods below 0deg C are injurious to the trees and at 13deg C growth diminishes. However, individual species and varieties decrease in susceptibility to low temperatures in the following sequence: grapefruit, sweet orange, mandarin, lemon/lime and trifoliate orange as most hardy. Temperature plays an important role in the production of high quality fruit. Typical coloring of fruit takes place if night temperatures are about 14deg C coupled with low humidity during ripening time. Exposure to strong winds and temperatures above 38deg C may cause fruit drop, scarring and scorching of fruits. In the tropics the high lands provide the best night weather for orange color and flavor.

Depending on the scion/ rootstock combination, citrus trees grow on a wide range of soils varying from sandy soils to those high in clay. Soils that are good for growing are well-drained, medium-textured, deep and fertile. Waterlogged or saline soils are not suitable and a pH range of 5.5 to 6.0 is ideal. In acidic soil, citrus roots do not grow well, and may lead to copper toxicity. On the other hand at pH above 6, fixation of trace elements take place (especially zinc and iron) and trees develop deficiency symptoms. A low pH may be corrected by adding dolomitic lime (containing both calcium and magnesium)

A citrus orchard needs continuous soil moisture to develop and produce, and water requirement reaches a peak between flowering and ripening. However, many factors such as temperature, soil type, location, plant density and crop age influence the quantity of water required. Well-distributed annual rainfall of not less than 1000 mm is needed for fair crop. In most cases, due to dry spells, irrigation is necessary. Under rain-fed conditions, flowering is seasonal.

There is a positive correlation between the onset of a rainy season and flower break. With irrigation flowering and picking season could be controlled by water application during dry seasons. Irrigation systems involving mini sprinklers irrigating only soil next to citrus trees have been developed as an efficient and water conserving irrigation method.

Agronomic aspects

Propagation

The most common method of citrus propagation is by budding. When old trees are top-worked, bark grafting is used. Citrus varieties grown from seed have numerous problems like late bearing, uneven performance due to their genetic variability and susceptibility to drought, root invading fungi, nematodes and salinity. Rootstocks are therefore used to meet all citrus requirements (tolerance / resistance to pests and diseases, suitability to soil and water conditions, as well as compatibility with scion variety selected). Rootstocks also improve the vigour and fruiting ability of the tree, as well as the quality, size, colour, flavour and rind-thickness of the fruit.

Citrus rootstocks have the following characteristics:

• Rough lemon (C. jambhiri). Seedlings produce a uniform and fast growing rootstock, which is easy to handle in the nursery. The plant develops a shallow but wide root system with a vigorous taproot. Trees budded on rough lemon produce an early, good yield but the fruit quality especially during the first years is not satisfactory. Trees are comparatively short-lived. Rough lemon prefers deep, light soil and do not tolerate poor drainage or waterlogging. It is tolerant to citrus tristeza virus but susceptible to Phytophthora spp., citrus nematodes and soil salinity. It is drought tolerant. Rough lemon can be budded with oranges, mandarins, lemons, limes and grapefruits. It is the most commonly used rootstock in East Africa.

• Cleopatra mandarin (Citrus reshni). It is suited to soils of heavier texture. On this rootstock, trees are slow growing with low yields in early years. Trees are long-lived. Its influence on fruit quality is good. It is tolerant to soil salinity. It is susceptible to poor drainage, Phytophthora spp. and citrus nematodes. It can be budded with oranges, mandarins and grapefruits.

• Trifoliate orange, Citrus trifoliata (syn. Poncirus trifoliata), It is a dwarfing stock and is most suitable for heavy and less well-drained soils. Rootstock propagation is slow, but budded trees yield heavily and produce high quality fruits. The plants develop abundant roots and often several taproots, which penetrate the soil deeply. It should not be used in calcareous soils. It is tolerant to Phytophthora spp. and citrus nematodes. It can be budded with oranges, mandarins and grapefruits.

• Carrizo / Troyer citrange (Citrus trifoliata x C. sinensis). Rootstocks are somehow difficult to establish. In order to promote fibre roots, young plants should be undercut as long as they are in the seedbed. Citranges are not suitable for very light and strongly alkaline soils. They are sensitive to overwatering but once established produce high quality fruits. They are somehow tolerant to Phytophthora spp. and citrus tristeza virus but susceptible to Exocortis viroid and citrus nematodes. They can be budded with oranges, mandarins and grapefruits.

• Citrumelo (Citrus trifoliata x C. paradisi). Plants produce an expansive root system and therefore have good drought tolerance. They can be used on a wide range of soils and produce an outstanding quality of fruit. They are tolerant to Phytophthora spp. but susceptible to citrus nematodes. They can be budded with oranges, tangerines and grapefruit.

• Rangpur lime (C. aurantifolia). This stock is suitable for various soil types, including deep sand. It prefers warm locations. It produces vigorous, well-bearing trees with a high degree of drought resistance. It is susceptible to Phytophthora spp. and citrus nematodes. It can be budded with oranges and grapefruits.

• Sweet orange (C. sinensis). This rootstock produces large and vigorous trees and is suitable for light to medium soils, which are well drained. It produces good quality fruits and the trees are long-lived. It has low drought tolerance and is very susceptible to Phytophthora spp. and citrus nematodes. It can be budded with oranges, mandarins and grapefruits.

• Sour orange (C. aurantium). An excellent rootstock in locations where citrus tristeza virus is not a problem since it is very susceptible to the disease. It is tolerant to poor drainage. It has low tolerance to drought. It produces very good quality fruits. It is tolerant to Phytophthora spp. but susceptible to citrus nematodes. It can be budded with oranges and grapefruits.

Planting

• Select seeds from healthy mother trees for rootstocks

• Hot water treat seeds at 50deg C for 10 minutes

• Seeds perform better when planted soon after they are extracted

• Sow seeds in seedbeds or polybags (18 x 23 cm). Seeds germinate in 2 to 3 weeks

• Water the seeds regularly, preferably twice a day until they germinate

• Seedlings are normally ready for budding when reaching pencil thickness or 6 to 8 months after germination.

• T-budding is the most common method.

• Do budding during warm months. Avoid budding during cold periods and during dry conditions

• Budded plants are ready for transplanting 4 to 6 months after budding

Alternatively, obtain budded plants from a registered fruit nursery. These budded plants should be ready for transplanting in the field.

Transplanting in the field

• Transplant in the field at onset of rains.

• Clear the field and dig planting holes 60 x 60 x 60 cm well before the onset of rains.

• At transplanting use well-rotted manure with topsoil.

• Spacing varies widely, depending on elevation, rootstock and variety. Generally, trees need a wider spacing at sea level than those transplanted at higher altitudes. Usually the plant density varies from 150 to 500 trees per ha, which means distances of 4 x 5 m (limes and lemons), 5 x 6 m (oranges, grapefruits and mandarins) or 7 x 8 m (oranges, grapefruits and mandarins). In some countries citrus is planted in hedge rows.

• It is very important to ensure that seedlings are not transplanted too deep.

• After transplanting, the seedlings ought to be at the same height or preferably, somewhat higher than in the nursery.

• Under no circumstances must the graft union ever be in contact with the soil or with mulching material if used.

Tree management / maintenance

• Keep the trees free of weeds.

• Maintain a single stem up to a height of 80-100 cm.

• Remove all side branches / rootstock suckers.

• Pinch or break the top branch at a height of 100 cm to encourage side branching.

• Allow 3-4 scaffold branches to form the framework of the tree.

• Remove side branches including those growing inwards.

• Ensure all diseased and dead branches are removed regularly.

• Careful use of hand tools is necessary in order to avoid injuring tree trunks and roots. Such injuries may become entry points for diseases.

• As a general rule, if dry spells last longer than 3 months, irrigation is necessary to maintain high yields and fruit quality. Irrigation could be done with buckets or a hose pipe but installation of some kind of irrigation system would be ideal.

• Citrus is under irrigation in the major citrus world producing countries.

Manure and fertilizer

For normal growth development (high yield and quality fruits), citrus trees require a sufficient supply of fertiliser and manuring. No general recommendation regarding the amounts of nutrients can be given because this depends on the fertility of the specific soil. Professional, combined soil and leaf analyses would provide right information on nutrient requirements. In most cases tropical soils are low in organic matter.

To improve them at least 20 kg (1 bucket) of well-rotted cattle manure or compost should be applied per tree per year as well as a handful of rock phosphate. On acid soils 1-2 kg of agricultural lime can be applied per tree spread evenly over the soil covering the root system. Application of manure or compost makes (especially grape-) fruits sweeter (farmer experience).

Nitrogen can be supplied by intercropping citrus trees with legume crops such as mucuna, cowpeas, clover or dolichos beans, and incorporating the plant material into the soil once a year. Mature trees need much more compost/well-rotted manure than young trees to cater for more production of fruit. Conventional fertilization depend on soil types, so it is recommended to consult the local agricultural office.

Husbandry

In windy areas, a windbreak should be provided as citrus is sensitive to strong winds. A windbreak provides protection at orchard tree level for about 4-6 times its height.

• Plant the windbreak as close as possible and at right angles to prevailing winds.

Symptoms of mineral deficiency

|

Nutrient Element |

Leaves |

Fruit |

Tree growth |

|

Nitrogen |

Pale yellow to old ivory |

Reduced crop |

Reduced. May produce abundant bloom. Flower buds may fall without opening |

|

Phosphorous |

Small, dull |

Reduced crop. Large. Puffy, bumpy surface, enlarged core cavity and thick rind. |

Reduced |

|

Magnesium |

Yellow mottling along margin. Developing a green wedge to "Christmas tree" pattern. Eventual complete yellowing and defoliation. |

Reduced crop |

Reduced |

|

Iron |

Yellow veins, remain green until final stage of general chlorosis. Reduced size |

Reduced crop |

Eventually reduced |

|

Zinc |

Mottled yellow between main veins. Small narrow Early fall. Reduced size |

Reduced crop, some pale yellow off types |

Eventually reduced |

|

Manganese |

Normal green along main veins. Rest of leaf pale green to light yellow |

Reduced crop |

Eventually reduced |

|

Potassium |

Old leaves curl and loose their green colour |

Small, smooth, thin rind, drop prematurely |

Reduced |

|

Copper |

Deep green, oversized, then darkened |

Splitting and gumming. Dark brown gum soaked eruptions. May turn black. Gum in centre core |

Twigs enlarge at nodes, blister and die back. Gum pockets. “Cabbage head" growth |

Intercropping

Intercropping with shallow rooted crops such as vegetables, herbs, green manure legumes sweet potatoes etc, is recommended in order to keep the soil cultivated around citrus trees.

Harvest, post-harvest practices and markets

Harvest

Citrus fruits are best harvested when they are mature, as this ensures they have developed their full flavor and nutritional content. The maturity of citrus fruits can be identified by changes in their color, especially in regions where the night temperatures are around 14°C and there is low humidity. As the fruits ripen, their color transforms from green to vibrant shades of orange, yellow, or pink, depending on the variety.

In low-altitude areas citrus fruits may not change color, it becomes necessary to conduct maturity tests. A sample of fruits can be randomly selected and examined for signs of maturity, such as firmness, size, and internal juice content. This practice ensures that fruits are harvested at the optimal time for maximum quality.

During harvesting, it is essential to handle the fruits with care to maintain their good condition. Use of a sharp knife is recommended to cut the fruits from the tree carefully. By employing this method, growers can avoid damaging the fruits and ensure a clean cut, reducing the risk of bruising and post-harvest injuries.

Alternatively, some farmers may opt to pluck the fruits directly from the tree by hand. This technique has its drawbacks as it often leads to the stem breaking too close to the fruit. When the stem is broken in such a way, it creates an entry point for potential infections, pests, or diseases that could affect the fruit's quality during storage and transportation.

Post-harvest practices

After harvesting, the fruits are thoroughly cleaned to remove any dirt or residues. Grading involves sorting the fruits based on their size, color, and overall quality. This ensures that consumers receive uniform and visually appealing fruits. Deformed and infected fruits are discarded. Finally, the citrus fruits are carefully packed in aerated containers, such as boxes or crates, to protect them during transportation.

To extend the shelf life of citrus fruits, post-harvest treatments like waxing and cold storage are commonly used. Applying a thin layer of wax to the fruit's surface helps reduce moisture loss and preserves freshness. Cold storage, at controlled temperatures, slows down the ripening process and minimizes spoilage.

(Strano, M. et al.,2022.

Value addition and markets

The citrus fruit market is vast and diverse, with both local and global demand. Locally, citrus fruits are sold in grocery stores, supermarkets, and farmer's markets. They are also used in various food and beverage industries to make juices, jams, and flavorings.

Export plays a significant role in the citrus fruit market. Many citrus-producing countries export their surplus to international markets. The major export destinations include North America, Europe, and Asia. Factors like taste, freshness, and price influence the competitiveness of citrus fruits in these markets.

Pixie oranges are gaining importance in the Kenyan market. They are mainly produced in Makueni and Kitui counties. The recommended spacing is about 3-4 within rows and about 5m between the rows. A hectare can fit about 900 trees giving about USD 20,000 per year. A grafted tree can give 60 kg per year and will start bearing fruit after 2-3 years. High yields are attained at about the 5th year, by when a tree may have 300 or more fruits.

Nutritional value and recipes

Nutritive value per 100 g of edible portion

Proximate composition and dietary energy |

Lemon, pulp, raw |

Lemon, juice, home squeezed |

Lime, juice |

Orange, Juice |

Orange, pulp, raw |

Tangerine, pulp, raw |

Recommended daily allowance (approx.) for adults a |

Edible conversion factor, |

0.66 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

0.75 |

0.75 |

|

Energy (kj) |

155 |

198 |

125 |

77 |

176 |

218 |

9623 |

Energy (kcal) |

37 |

47 |

30 |

18 |

42 |

52 |

2300 |

Water (g) |

89.5 |

87 |

90.3 |

94.6 |

87.6 |

86.2 |

2000-3000c |

Protein (g) |

0.82 |

0.6 |

0.7 |

0.4 |

0.9 |

0.87 |

50 |

Fat (g) |

0.2 |

0.2 |

0.2 |

0.1 |

[0.2] |

0.2 |

<30 (male), <20 (female)b |

Carb (g) |

6.7 |

9.5 |

4.3 |

3.6 |

7.5 |

10.8 |

225 -325g |

Fibre (g) |

2.5 |

2.5 |

4.1 |

1.1 |

3.1 |

1.5 |

30d |

Ash (g) |

0.3 |

0.25 |

0.4 |

0.4 |

0.7 |

0.4 |

|

Mineral composition |

|

||||||

Ca (mg) |

33 |

20 |

26 |

21 |

23 |

26 |

800 |

Fe (mg) |

0.3 |

0.3 |

0.3 |

0.7 |

0.2 |

0 |

14 |

Mg (mg) |

15 |

12 |

11 |

11 |

10 |

17 |

300 |

P (mg) |

16 |

10 |

20 |

20 |

13 |

17 |

800 |

K (mg) |

120 |

120 |

150 |

146 |

165 |

150 |

4,700f |

Na (mg) |

2 |

2 |

3 |

2 |

5 |

2 |

<2300e |

Zn (mg) |

0.1 |

0 |

0 |

0.08 |

0.05 |

0.1 |

15 |

Se(mg) |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

30 |

Bioactive compound composition |

|

||||||

Vit A-RAE (mcg) |

1 |

1 |

2 |

3 |

5 |

1 |

800 |

Vit A RE (mcg) |

2 |

2 |

5 |

7 |

9 |

2 |

800 |

Retinol (mcg) |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1000 |

β-carotene equivalent (mcg) |

10 |

10 |

28 |

42 |

57 |

10 |

600 – 1500g |

Thiamin (mg) |

0.03 |

0.02 |

0.03 |

0.06 |

0.04 |

0.08 |

1.4 |

Riboflavin (mg) |

0.02 |

0.01 |

0.02 |

0.02 |

0.03 |

0.05 |

1.6 |

Niacin (mg) |

0.2 |

0.2 |

0.2 |

0.1 |

0.2 |

0.3 |

18 |

Folate (mcg) |

11 |

11 |

6 |

44 |

52 |

24 |

400f |

Vit B12 (mcg) |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

3 |

Vit C (mg) |

44 |

44 |

41 |

[64] |

45 |

36 |

60 |

Source (Nutrient data): FAO/Government of Kenya. 2018. Kenya Food Composition Tables. Nairobi, 254 pp. http://www.fao.org/3/I9120EN/i9120en.pdf

a Lewis, J. 2019. Codex nutrient reference values. Rome. FAO and WHO

b NHS (refers to saturated fat)

c https://www.hsph.harvard.edu/nutritionsource/water/

d British Heart Foundation

e FDA

f NIH

g Mayo Clinic

Recipes

1. Kenyan Kachumbari (Salad)

Ingredients

3 medium sized onions

4 medium sized tomatoes

Salt to taste

3 tbsp lemon juice

2 tbsp chopped dhania

1 green chili

Preparation

• Peel and slice onions very thinly

• Sprinkle them with salt and keep aside for sometime

• Gently squeeze the onions until soft. This helps in removing the bitterness from them

• Rinse with clean water

• Squeeze out excess liquid

• Slice tomatoes very thinly and mix with dhania, lemon, salt and green chili

• Add in the onions and mix

• Serve

Source: Adeka et al., 2005

2. Endimawu (Enimu) (Lemon water)

Source: Banyoro of Hoima, Uganda (Maundu et al. 2005)

Ingredients: Lime or lemon, water, sugar – optional

Procedure:

Cut limes into two halves

Prepare black tea in the normal way

Squeeze each half at a time to release its juice. You can squeeze directly into clean water or black tea

Mix by stirring.

Add a little sugar to taste (optional)

Served with:

Snacks e.g. bread, biscuits or other foods

Comments:

Lemon water is taken for cough, weight loss, diabetes or high blood pressure. Others used for making such flavoured drinks include lemon grass in its dried or fresh form. It is said to be good for constipation.

3. Mlenda with lemon

Ingredients

500 g bunches of mlenda (Jute, Corchorus olitorius)

2 medium sized tomatoes (diced)

1medium sized onion (diced)

¼ cup lemon (juice)

4tbsp peanut butter

3 tbsp ghee

1 cup coconut milk

Salt to taste

Preparation

• Pluck the leaves from the stalks

• Wash thoroughly and cut the leaves into small pieces

• Sprinkle the leaves with lemon juice and mix well

• Heat the ghee, fry onion lightly, add tomato and season to taste, stir

• Add the leaves, stir and cook for 10 minutes

• Mix groundnut powder with coconut milk, add in the cooking vegetable and stir

• Simmer for 5 minutes

• Serve with rice

Lemon juice removes the slimy consistency from the vegetable. The vegetable has a slight lemon taste

Source: Adeka et al., 2005

Fresh Quality Specifications for the Market in Kenya

The following specifications constitute raw material purchasing requirements.

|

|

© S. Kahumbu, Kenya

|

Information on Pests

General Information

Organic pest and disease management measures place priority on indirect control methods. Direct control methods are applied as a second priority.

Indirect Control Methods:

- Promotion of beneficial insects and plants by habitat management: organic orchard design, ecological compensation areas with hedges, nesting sites etc.

- Soil management: Organic compost and plant slurry to improve soil structure and soil microbial activity

- Pruning: : to remove died and diseased shoots/twigs and to provide good aeration of the trees

Direct Control Methods:

- Biological control: release of antagonists, natural predators and entomophagous fungi.

- Mechanical control methods.

- Organic pest and disease control products.

Examples of pests and organic control methods

There are a large number of citrus diseases caused by bacteria, mycoplasma, fungi and viruses. The following list contains some important examples. The organic citrus disease management consists in a 3-step system:

- Use of disease-free planting material to avoid disease problems

- Choosing rootstocks and cultivars that are tolerant or resistant to prevalent diseases

- Application of fungicides such as copper, sulphur, clay powder and fennel oil. Copper can control several disease problems. However, it must not be forgotten that high Copper accumulations in the soil is toxic for soil microbial life and reduce the cation exchange capacity

|

Scales are small insects (1.0 to 7 mm long), which resemble shells glued to the plant. There are many species (types) of scales on citrus, which vary in shape (round to oval) and colour according to the species.

There are two main groups: hard (armoured) and soft (naked). The armoured scales are the most serious pests. The most important armoured scales attacking citrus are the red scale (Aonidiella aurantii), the mussel purple scale (Lepidosaphes beckii), and the circular scale (Chrysomphalus aonidum). The most important soft scales are the soft brown scale (Coccus hesperidum) and the soft green scale (Coccus viridiis or C. alpinus).

Female scales have neither wings nor legs. Females lay eggs under their scale. Some species give birth to young scales directly. Once hatched, the tiny scales, known as crawlers, emerge from under the protective scale. They move in search of a feeding site and do not move afterwards. They suck sap on all plant parts above the ground. Their feeding may cause yellowing of leaves followed by leaf drop, poor growth, dieback of branches, fruit drop, and blemishes on fruits. Leaves may dry when heavily infested, and young trees may die.

Soft scales excrete honeydew, causing growth of sooty mould. In heavy infestations fruits and leaves are heavily coated with sooty mould turning black. Heavy coating with sooty mould reduces photosynthesis. Fruits contaminated with sooty mould loose market value. Ants are usually associated with soft scales. They feed on the honeydew excreted by soft scales, preventing a build-up in sooty moulds, but also protecting the scales from natural enemies. Armoured scales do not excrete honeydew. What to do:

|

| The citrus rust mite (Phyllocoptruta oleivora) The yellow tiny citrus rust mite attacks mainly the fruit. Its feeding causes the rind of the fruit to turn silvery, reddish brown, or blackish. One result of mite damage is small fruit, which deteriorates rapidly. This damage lowers the market value of the fruit. Heavy populations of the rust mite cause bronzing of leaves and green twigs, and general loss of vitality of the whole tree. Warm and humid conditions favour the development of rust mite.

What to do:

|

| Citrus bud mite (Aceria sheldoni) It is a tiny, worm-shaped, creamy white mite. It has only two pair of legs, and is hardly visibly without a magnifying glass. These mites occur in protected places such as under the bracts of buds. They attack the growing points of the twigs, causing malformation of the young leaves and flower buds. As a consequence, the growth of the trees is retarded. The fruit set can be seriously reduced and infested fruit may be malformed. Bud mites are more abundant during the hot season. Commonly found in developing and leaf buds. Damage under the bracts causes the death of the buds. Flower bud development is reduced, growth is retarded, branches become stunted and deformed, and rosette-shaped leaves are formed. The fruits, particularly in lemons are deformed. Almost all deformed fruits fall off at an early stage of development. Even light infestations may cause damage and control measures should be applied on time and regularly. Spots decrease the market value of the fruit and provide entry for fungal infection. Damage fruits loose moisture rapidly and do not keep well. Infestation on ripe fruits causes light yellow or silver discolouration. These mites attack all citrus species, but damage is usually worst in lemons. Damaged fruit could drop prematurely or assume abnormal shapes. The juice content of damaged fruit is significantly lower than that of normal fruit.

What to do:

|

| Several species of mealybugs attack citrus. They suck sap from tender leaves, petioles and fruit. Feeding on the fruit results in discoloured, bumpy, and scarred fruit, with low market value, or unacceptable for the fresh fruit market. Mealybugs excrete honeydew, which leads to the growth of sooty mould on fruit and leaves. Fruit cover with sooty mould at harvest must be washed. The most important is the citrus mealybug (Planoccous citri).

What to do:

|

| Certain ants are major indirect pests in citrus orchards. Although they do not damage the trees, they are associated to honeydew-producing insects such as soft scales, aphids, whiteflies, blackflies and mealybugs. Natural enemies often keep these insects under control; however, ants feeding on the honeydew give them indirect protection by disturbing natural enemies. As a result numbers of these honeydew producing insects, and indirectly other pests such as armoured scales, may rise to damaging levels.

Ant management does not imply eradication of all ants. There are many different types of ants in citrus orchards. Many of them are important predators of other insects, including pests of citrus. Some of the species that could be a problem due to their association with honeydew-producing insects (e.g. the big headed ant Pheidole megacephala and the pugnacious ant, Anoplolepis custodiens are also beneficial preying on a variety of insects, and are valuable predators on the ground. Therefore these ants should not be destroyed but kept off the trees.