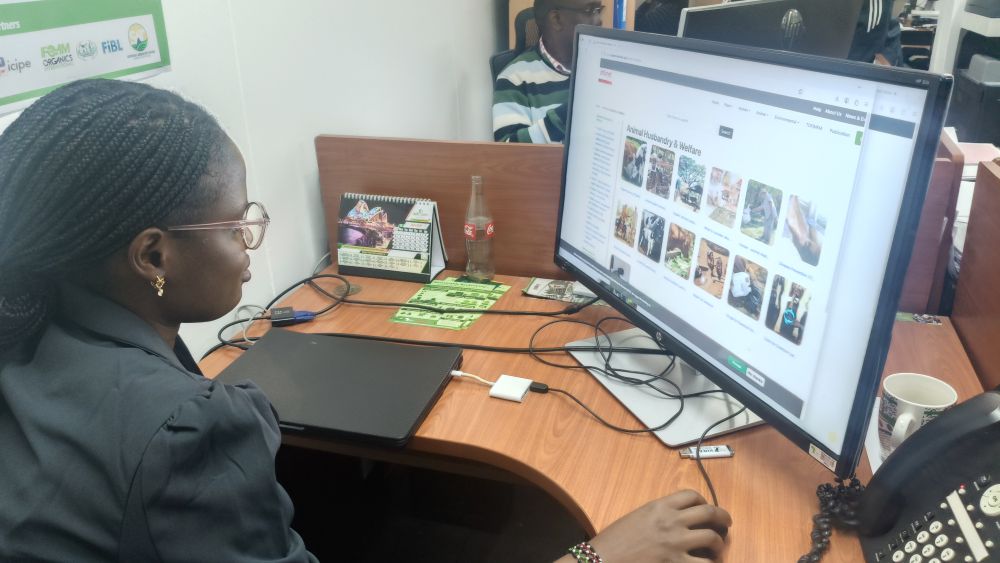

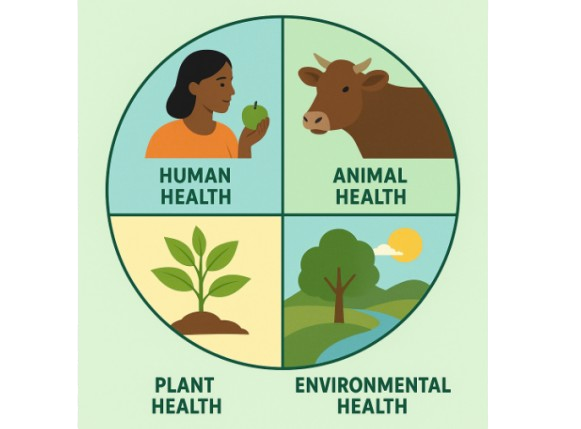

Infonet-Biovision: Advancing the One Health Approach for Sustainable Communities

Infonet provides practical information on nutrition, hygiene, and disease prevention, helping communities adopt healthy lifestyles and reduce exposure to preventable diseases.