|

African armyworm (Spodoptera exempta) Armyworms may cause severe defoliation in upland rice plants leaving only the stem. Armyworms are regarded as occasional pests, but during an outbreak they devastate rice crops. |

|

|

What to do:

|

|

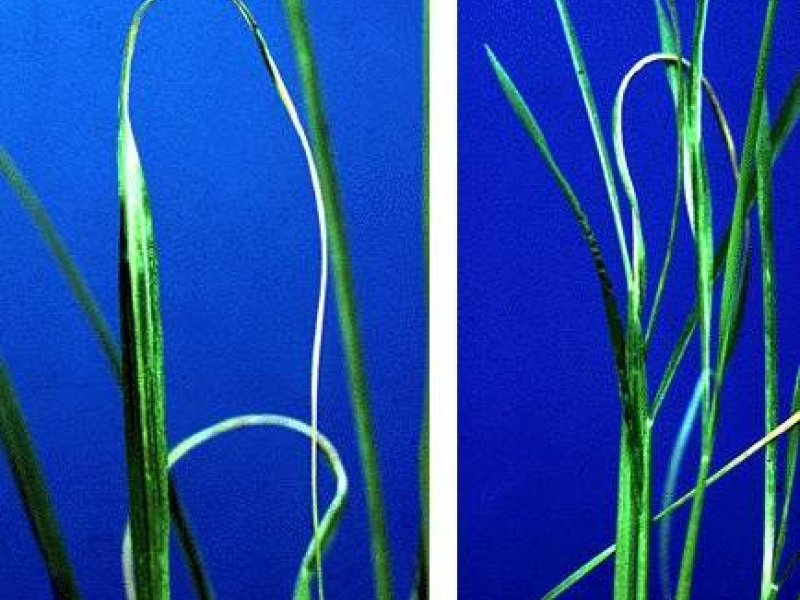

African gall midge (Orseolia oryzivora) It is a small reddish-brown midge (similar to a mosquito) 4 to 5 mm long. Females lay up to 300 eggs on rice leaf sheaths. Upon hatching, the small maggots wiggle down to the leaf blade and move between the leaf sheath and the stem until the growing points where they feed for 2 to 3 weeks. Larval feeding induces development of light swellings or galls, which are inconspicuous until larvae are ready to pupate. The galls are long cylindrical, about 3 mm in diameter and from a few cm up to 1 to 1.5 m long. They are often silvery white and resemble an onion leaf, hence they are generally known as 'silver shoots' or 'onion leaf galls'. Galls generally appear about 20 to 40 days after the crop has been transplanted. Gall midges can cause serious damage from the seedling stage to panicle initiation. Attacked tillers do not produce panicles. Galled plants may tiller profusely to compensate for loss of growing points. A serious attack results in stunted plant growth and poor yields. Gall midges do not attack rice plants that have matured beyond tillering stage. These midges spent some generations on wild grasses and then move to attack young rice plants. They are pests during the rainy season, and are most serious on rain-fed lowland and irrigated rice.

|

|

|

What to do:

|

|

Bacterial leaf blight (Xanthomonas oryza pv. oryza) The first symptom of the disease is a water soaked lesion on the edges of the leaf blades near the leaf tip. The lesions expand and turn yellowish and eventually greyish-white and the leaf dries up. High rainfall with strong winds provides conditions for the bacteria to multiply and enter the leaf through injured tissue. |

|

|

What to do:

|

|

Blast (Pyricularia oryzae (Magnaporthe grisea) This disease can cause serious losses to susceptible varieties during periods of blast favourable weather. Depending on the part of the plant affected, the disease is often called leaf blast, rotten neck, or panicle blast. The fungus produces spots or lesions on leaves, nodes, panicles, and collar of the flag leaves. Leaf lesions range from somewhat diamond-shaped to elongated with tapered, pointed ends. The centre of the spot is usually grey and the margin brown or reddish-brown. Both the shape and colour of the spots may vary and resemble those of the brown leaf spot disease. Blast differs from brown leaf spot in that it causes longer lesions and develops more rapidly.

The blast fungus frequently attacks nodes at the base of the panicle and the branches of the panicle. If the panicle is attacked early in its development, the grain on the lower portion of the panicle may be blank giving the head a bleached whitish colour, giving the name "blasted" head or rice "blast". If the node at the base of the panicle is infected, the panicle breaks causing the "rotten neck" condition. In addition, the fungus may also attack the nodes or joints of the stem. When a node is infected, the sheath tissue rots and the part of the stem above the point of infection often is killed. In some cases, the node is weakened to the extent that the stem will break causing extensive lodging. Blast generally occurs scattered throughout a field rather than in a localised area of the field. Late planting, frequent showers, overcast skies, and warm weather favour development of blast. Spores of the fungus are produced in great abundance on blast lesions and can become airborne, disseminating the fungus a considerable distance. High nitrogen fertilisation should be avoided in areas that have a history of blast.

|

|

|

What to do:

|

|

Brown leaf spot (Bipolaris oryzae) This disease was previously called Helminthosporium leaf spot. Most conspicuous symptoms of the disease occur on leaves and glumes of maturing plants. Symptoms also appear on young seedlings and the panicle branches in older plants. Brown leaf spot is a seed-borne disease. Leaf spots may be evident shortly after seedling emergence and continue to develop until maturity.

Leaf spots vary in size and are circular to oval in shape. The smaller spots are dark brown to reddish brown, and the larger spots have a dark-brown margin and reddish brown to grey centres. Damage from brown spot is particularly noticeable when the crop is produced in nutritionally deficient or otherwise unfavourable soil conditions. Significant development of brown spot is often indicative of a soil fertility problem.

|

|

|

What to do:

|

|

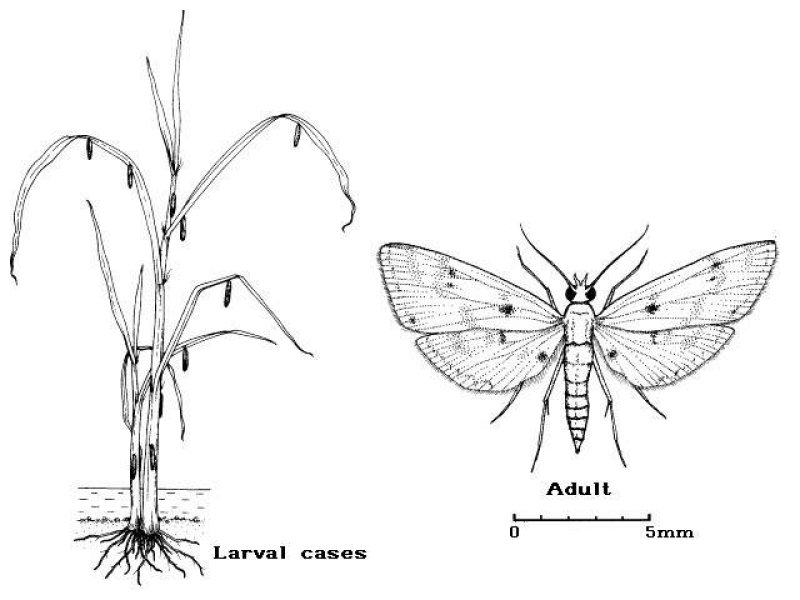

Case worm (Nymphula depunctalis - Parapoynx stagnalis) The case worm is a common pest on wetland rice. Moths are small (1 to 1.2 cm in wingspan) with white markings and black specks on the wings. Females lay eggs in small batches (about 20) on the lower side of leaves that are floating on the water surface. Upon hatching caterpillars are yellow to green with light brown heads. They climb onto a leaf and begin feeding by scrapping the leaf surface causing linear grazing of leaves giving the leaf tissue a ladder-like appearance. Later caterpillars cut a piece of rice leaf, roll it up into a case and seal the edges with silk material leaving the interior end open. The cut near the tip of a leaf is characteristic. At all times the caterpillar is likely to be partly or wholly enclosed in its portable leaf case. The caterpillar attacks the food plant only in the vegetative stage, during the first 4 weeks after transplanting. Caterpillars of the case worm are semi-aquatic, ascending the plants at night to feed. Heavy infestation on small seedlings may completely destroy a rice crop. Damaged plants may recover but crop maturation may be delayed about a week. Yield loss may occur when the caseworm occurs in combination with other non-defoliating insects such as whorl maggots and stemborers. Damaged plants are stunted and produce fewer tillers.

|

|

|

What to do:

|

|

Damping-off diseases Failure of seedlings to emerge is the most obvious symptom of seed rot and pre-emergence damping off. Examination may reveal a cottony growth of mycelium (mould) in and around seed coats and the emerging seedlings, indicating attack by water mould(s). The growing point or root of germinated seedlings has a dark brown discolouration or rot. The base of the leaf sheath and the roots of emerged seedlings have a similar dark brown or reddish-brown rot. Affected seedlings appear stunted and yellow and may soon wither and die (seedling blight). Water moulds are particularly severe in water-seeded rice culture. In areas where fields are frequently water-seeded, it has become difficult to obtain adequately dense and uniform stands. Seed rots caused by the water moulds Pythium and Achlya, and to a lesser extent by the fungus Fusarium, have been identified as the causes of the problem. These fungi often act as a complex within affected fields. Symptoms of water mould can be observed through the flood water as balls of fungal strands radiating from seeds on the soil surface. When the water is removed using the critical point method of water-seeding, affected seeds are surrounded by a mass of fungal strands. This results in circular, copper brown or dark green spots on the soil surface, about the size of a penny, with the rotted seed at the centre. The colours of the spots are the result of bacterial and algal growth. Seed rot by water moulds is favoured when the water temperature is unusually high or low. If seedlings are attacked after germination at pegging, seedlings become yellow and stunted and grow poorly.

|

|

|

What to do:

|

|

Flea beetles (Chaetocnema spp.) Flea beetles make small holes in the leaf when feeding, however, this damage is considered minor. Most important, these beetles are potential vectors of the Rice Yellow Mottle Virus. Flea beetles are small, and have enlarged hind legs and jump when disturbed.

|

|

|

What to do:

|

|

Hispid beetles (Trichispa spp., Dicladispa viridicyanea, Dactylispa bayoni) Hispid beetles are serious pests of rice in some countries in Africa, causing severe defoliation and as vectors of the Rice Yellow Mottle Virus. Adult beetles have numerous spines on thorax and abdomen. Trichispa sericea is the most common of the hispid beetles. The adult is a dark grey beetle covered with spines, and about 3 to 4 mm long. Females lay eggs singly in slits made under the epidermis of the upper portion of the leaf. Eggs are white, boat-shaped and about 1 mm long. Upon hatching, the grubs (larvae) mine within the leaf. Grubs are slender, yellow and about six mm long. They pupate in the mine. When infested leaves are held against the light, the grub or pupa may be seen as a dark spot in the mine. Hispid beetles attack the crop in the early growth stages. Larval feeding occurs during the tillering stage. The first attack in a field is highly localised, but the infested area spreads rapidly. Feeding by adults on the leaves causes characteristic narrow white streaks or feeding scars that run along the long axis of the leaf. Mining by grubs within the leaf shows as irregular pale brown blister-like patches. Feeding results in loss of chlorophyll and the plants wither and die. The most serious damage occurs in nurseries, which may be completely destroyed. Severe infestations sporadically occur on transplanted rice and can kill the plant. When the plants survive, they usually recuperate and produce some grain. However, damaged plants often mature late. Hispid beetles are prevalent in wetland environments, especially irrigated lowland fields. They are generally most abundant during the rainy season.

|

|

|

What to do:

|

|

Rice root-knot nematode (Meloidogyne graminicola) Symptoms consist of characteristic hooked-like galls on roots, newly emerged leaves appear distorted and crinkled along the margins, and infested plants are stunted and yellow. Heavily infested plants flower and mature early. The rice root-knot nematode is a damaging parasite on upland, lowland and deepwater rice. It is well adapted to flooded conditions and can survive in waterlogged soil as eggs in egg-masses or as juveniles for long periods. Numbers of nematodes decline rapidly after 4 months but some egg masses can remain viable for at least 14 months in waterlogged soil. This root-knot nematode can also survive in soil flooded to a depth of one m for at least 5 months. It cannot invade rice in flooded conditions but quickly invades when infested soils are drained. It can survive in roots of infected plants. It prefers soil moisture of 32%. It develops best in moisture of 20% to 30% and soil dryness at rice tillering and panicle initiation. Its population increases with the growth of susceptible rice plants.

|

|

|

What to do:

|

|

Rice-sucking bugs, stink bugs (Aspavia spp, Nezera viridula), and Alydid bugs (Mirperus spp.and Riptortus spp.) Stink bugs produce a strong odour when disturbed. Adult Aspavia bugs are brown bugs with a large triangular shield on the back having three yellow spots and a spine at each side of the thorax. Nezera viridula is green and about 1.2 cm long. Alydid bugs have a long slender body and lack a triangular shield on the back. Riptortus is stout and varies from light to dark brown; the hind legs are enlarged. Both nymphs and adult bugs feed sucking rice grains in the milky stage. When grains have ripened the bugs feed on panicle stalks and pedicels. Riptortus bugs also feed on hard dough rice grains. Bug feeding causes pecky rice that is partially or wholly stained due to infections with bacteria and fungi. The glumes change colour first to light brown, then darker and may turn grey in severe cases. Damage grains are shrivelled and unfilled. Severity of the damage depends on the stage of grain development and on the number of punctures in the grain.

|

|

|

What to do:

|

|

Rice whorl maggots (rice leafminers) (Hydrellia spp.) The rice whorl maggot (Hydrellia prosternalis) has been reported from West Africa. Another species Hydrellia sp. has been reported in Kenya (NIB, 1995). Adults of the rice whorl maggot and rice leafminers are small flies (1.5 to 3 mm long), grey to black in colour with silvery white or golden brown markings on the lower part of the head. They lay white cigar-shaped eggs on the leaves. Upon hatching the maggots of the leafminers penetrate the leaf tissue and feed in between the 2 layers of the leaf causing mines parallel to the veins. Maggots may pupate in an existing mine or migrate to a different leaf to form a new mine. High humidity (80-100% relative humidity) is required for leafminer development, therefore, mines are typically observed in leaves close or lying on the water surface. Whorl maggots start feeding on the leaf margins causing large scarred areas giving the leaf a ragged appearance and causing eventual leaf collapse. Eventually the maggots enter the whorl and tunnel the plant's developing stem.

Feeding damage by leafminers retards plant development, reduces plant vigour and renders infested plants less competitive with weeds. Plant vigour and weather conditions affect the extent and seriousness of the damage caused by the rice leafminer. Damage extent is closely related to the speed the plant growths erect and out of the water. Any factor affecting plant growth, which increases the number of leaves remaining lying on the water, or the length of time they are fully in contact with water will increase damage. The plant is usually able to produce additional leaves, but continued mining can result in reduced tillering, greater susceptibility to later pest attack, delayed maturity, or death of the plant. Once leaves start growing upright above the water, the rice leafminer does not cause economic damage. Attack by the whorl maggot may kill young plants (2 to 6 weeks after emergence) depending on the severity of the damage. Plants that survived damage are eventually drowned by the flood, or plant stands get so thinned that are easily overwhelmed by weeds. Other leaf-mining fly (Creodont orbiting) has been reported as a minor pest in West Africa. This leaf-mining fly is widely spread in the rice-growing region in Ghana, but it is of no apparent economic importance. The adult is a small fly (about 1.6 mm long). Females lay eggs into the leaf tissue, and the maggots feed forming mines towards the leaf tip. Maggots pupate within the mines. Symptoms of damage are the transparent, light brown mines that are elongated along one side of the midrib reaching up to 6 cm in length.

|

|

|

What to do:

|

|

Rice Yellow Mottle Virus (RYMV) (Sobemovirus) Rice yellow mottle virus is endemic in Africa, was first reported in Kenya in 1966, but is now known to occur in almost all irrigated rice growing areas in Africa. This disease can cause up to 92% yield loss on "Super", the most popular rice variety in Tanzania.

RYMV causes severe infections mainly in irrigated rice and is transmitted by beetles (Sesselia pusilla, Chaetocnema pulla, Trichispa sericea and Dicladispa viridicyanea) and mechanically. It is not seed transmitted.

Major symptoms of the disease are yellowing of leaves, stunting of affected plants, reduced tillering of the affected plants and sterility of the seed/grain.

|

|

|

What to do:

|

|

Stemborers Several species of stemborers attack rice. The more important are the striped borer (Chilo partellus), Chilo zacconius, Chilo orichalcocilielus, the white rice borer (Maliarpha separatella), the yellow borer (Scirpophaga sp.) and the pink stemborer (Sesamia calamistis). The caterpillars bore into the stem of rice plants. Caterpillars of the yellow borer bore into the stem below the growing point, destroying tillers. The white borer and the pink stemborer attack rice at full tillering stage preventing grains from filling up and ripening. This damage results in empty panicles known as "whiteheads". The striped borer feed on rice plants at all stages. Young caterpillars cause "dead hearts". |

|

|

What to do:

|

|

Stalk-eyed shoot flies (Diopsis spp.) The dark brown flies are about 8 mm in length, and have the eyes situated on 2 long stalks projecting from both sides of the head. Flies lay eggs singly on the upper surface of young leaves, or on the leaf sheath of older plants. The whitish maggots that hatch from the eggs penetrate into the growing zone (heart) of the plant. As a result of maggot feeding the central whorl does not open, but dries-up and dies, producing what is commonly known as "dead heart". Maggots move readily from one tiller to another. One maggot can destroy up to 10 neighbouring tillers. Later generations feed on the developing flower head. Pupation normally occurs in the first 3 leaf sheath of healthy tillers, generally one pupa per tiller. A severe attack is likely to occur when water levels are low. Such attacks reduce yields of rice plants. Shoot fly attack rice plants early in the crop growth stage, shortly after emergence in direct-seeded fields or shortly after transplanting. They are present throughout the crop growth period, although infestation is low in the flowering-ripening stages.

|

|

|

What to do:

|

|

Storage pests (Sitophilus oryzae, Rhyzopertha dominica) The most serious pests of stored rice are the rice weevils (Sitophilus oryzae) and the lesser grain-borer (Rhyzopertha dominica). Good store hygiene plays an important role in limiting infestation by rice weevil.

|

|

|

What to do:

|

|

Termites (Microtermes spp., Ancistrotermes spp., Trinervitermes spp., Macrotermes spp., and Odontotermes spp.). Termites, also known as white ants are common pests of upland rice in West Africa where they may cause serious damage during dry periods. They may also occur in lowland areas in light texture soils. They generally attack plants in their later growth stage by hollowing out their root system and filling it with soil resulting in the lodging of the rice plants. The attacked plants are then predisposed to further damage by ground-dwelling pests such as rodents, ants, and secondary infection by fungi and bacteria. Damaged plants can easily be pulled up by hand because the roots are severed.

|

|

|

What to do:

|

|

White tip nematode (Aphelenchoides besseyi) Rice is the most important host worldwide. Other host plants include; strawberry, onion, garlic, sweet corn, sweet potato, soybean, sugar cane, horseradish, lettuce, millet, many grasses, orchids, chrysanthemum, marigold, Mexican sunflower, African violets, and rubber plant (Hibiscus brachenridgii). Feeding of the nematodes at leaf tips in rice results in whitening of the top 3 to 5 cm of the leaf leading to necrosis (described as "White Tip" of rice). There is also distortion of the flag leaf that encloses the panicle. Diseased plants are stunted, lack vigour and produce small panicles. Affected panicles show high sterility, distorted glumes and small and distorted kernels.

|

|

|

What to do:

|

Geographical Distribution in Africa

Geographical distribution of Rice in Africa. Updated on 10 July 2019. Source FAOSTAT. © OpenStreetMap contributors. © OpenMapTiles, GBIF. https://www.gbif.org/species/2703459

Oryza sativa is believed to have originated in East and Southeast Asia, particularly in the regions around the Yangtze River in China and the Ganges River in India. It is one of the oldest cultivated crops, with a history dating back thousands of years. Recent phylogenetic studies have shown that both O. sativa subspecies, japonica and indica, were domesticated from wild rice Oryza rufipogon 8,200 to 13,500 years ago. O. sativa subsp japonica originated from a particular Oryza rufipogon population in the middle Pearl River region of Southern China, while O. sativa subsp indica emerged later through crosses between japonica and local wild rice as the initial cultivars spread into South East and South Asia.

African rice is indigenous to Africa, primarily in the southwestern region of West Africa. It's also cultivated as far east as Lake Chad, especially in the seasonally flooded Sahel lands near the Niger, Volta, and other rivers. It has been introduced to India and potentially reached Brazil through 17th-century Portuguese explorers. Furthermore, it has been cultivated in El Salvador and Costa Rica.

(National Academies of Sciences, 1996, Kew botanical gardens, GBIF secretariat, 2021)

Further info O. sativa geographical : https://powo.science.kew.org/taxon/urn:lsid:ipni.org:names:316812-2

Read more

Burkina Faso: Moui

Cameroon; Riz (local French) (O. sativa); Erisi (Banyong) (O. glaberrima) (National Academies of Sciences, 1996).

DRC: Loso (Kiyaka); Mupunga (Swahili); Losa (Lingala); Loso (Kikongo) (O. sativa);

Guinea: Baga-malé, Malé, Riz des Baga (O. glaberrima) (National Academies of Sciences, 1996).

Kenya: Mchele (husked rice), Mpunga (Upland rice) (Swahili); Musele (Kamba); Mushere, Mũceere (Gikuyu)

Mali: Issa-mo (river rice), Mou-bér (great rice) (O. glaberrima) (National Academies of Sciences, 1996).

Mauritius; Riz, Arishi Ou Nellou

Madagascar: Vary

Morocco: Uz, Rawz (Moroco); Mârô (Tekna, Moresque, Occidental Sahara), Riz (local French)

Nigeria: Iresi (Yoruba), Osi-Kakpa (Igbo), Chinkafa (Hausa)

Rwanda; Umuceri

Sierra Leone; Mba; Res (Krio), Mba (Mende), A - Pola (Temne) (O. sativa); Kebelei, Mba, Mbei (Mende), Mala (Kissi), Kono, Pa (Temne) (O. glaberrima) (National Academies of Sciences, 1996).

General Information and Agronomic Aspects

Introduction

Oryza sativa (Rice) also known as the Asian rice is a species of annual grass in the grass family Poaceae and the genus oryza. The Oryza genus consists of more than 20 species, two of which are cultivated: common rice (O. sativa) and African rice (O. glaberrima).

©Maundu 2005

Rice is believed to have originated in Asia, most likely in the region encompassing present-day China and India. From there, it spread across the continents through trade and agricultural practices. Today, it is cultivated in a wide range of climates, making it one of the most extensively distributed crops worldwide.

Rice thrives in warm, tropical and subtropical regions, where it can grow both in flooded fields (paddy or lowland rice) and on well-drained uplands (upland rice). It is a water-dependent crop, with paddy rice requiring standing water during parts of its growth cycle.

As a staple food, rice provides a major source of dietary energy for billions of people around the world. The grain is consumed in various forms, such as boiled rice, fried rice, rice cakes, and rice noodles, making it a versatile ingredient in countless dishes. Apart from its significance as a food crop, rice plays a vital role in cultural traditions, ceremonies, and rituals in many Asian societies. It is also used in traditional medicine and in the production of alcoholic beverages like sake in Japan.

Rice is primarily a source of carbohydrates, particularly starch, which provides a readily available source of energy. It is low in fat and contains essential nutrients, including protein, B-complex vitamins, and minerals such as iron and manganese. Brown rice, with its bran intact, is more nutritious, containing fiber and additional vitamins and minerals compared to polished white rice.

Ⓒ Adeka et al., 2005

The rice industry has seen significant value addition over the years, with the production of processed rice products like rice flour, rice bran oil, and rice-based snacks becoming popular.

In the global market, key producers and exporters of rice include countries like China, India, Thailand, Vietnam, and the United States. Africa is also a significant player in the rice market, with countries like Nigeria, Egypt, and Senegal being major producers and consumers within the continent.

(Meertens, H.C.C., 2006, Rokni, 2013, OECD, 2004, OECD, 1999).

Uses

Rice is cultivated primarily for the grain, which is a main staple food in many countries, especially in Asia. In Kenya it is becoming increasingly popular, especially in urban centres. From 2010 to 2014, Kenya had a yearly production of about 119,000 metric tons (FAOSTAT, 2014). Consumption of wheat has been on a steady increase from 410,000 metric tons in 2010 to 564,000 metric tons in 2014 (Economic Review of Agriculture, 2015). This increase in demand and the development of new upland varieties have created an opportunity for farmers to venture into rice growing.

Rice will give the same or better yield as maize and fetch the double price on the market at harvest time. Grains are quite nutritious when not polished. Common or starchy types are used in various dishes, cakes, soups, pastries, breakfast foods, and starch pastes; glutinous types, containing a sugary material instead of starch, are used in the Orient for special purposes as sweetmeats. Grain is also used to make rice wine, "Saki", much consumed in Japan. Rice hulls are sometimes used in the production of purified alpha cellulose and furfural (an industrial chemical derived from a variety of agricultural by-products, and commonly used as a solvent). Rice straw is used as roofing and packing material, feed, fertiliser, and fuel.

Species accounts

Oryza sativa is an annual or perennial tufted grass typically growing to a height of 0.5 to 1.8 m high (up to 5 m in deep water species) with usually 4 to 5 tillers. Leaves: long, slender, and lance-shaped, with a prominent midrib. They are usually green but can vary in color depending on the specific variety. Inflorescence: a panicle, 50 cm long, bearing 50 to 500 spikelets. Spikelets contain 3 flowers, 2 of which are sterile. Fruit is a whitish to brownish grey, ovoid or ellipsoid caryopsis. Fruits: grain, commonly referred to as a rice kernel. These grains are what humans harvest and consume. They vary in size, shape, and color depending on the specific variety of rice.

Oryza sativa contains two main subspecies:

• Oryza sativa subsp. japonica (Japonica rice) - is mainly cultivated in temperate regions like Australia, northern China, Japan, and Europe. Variety if short-grained and when cooked, it has a moist and sticky texture. Japonica rice makes up 15% of the world's rice production and often achieves higher yields than indica rice.

• Oryza sativa subsp. indica (Indica rice)- predominant variety, constitutes over 80% of worldwide rice cultivation. Typically cultivated in tropical and subtropical regions, Indica rice, when cooked, exhibits a distinct fluffy, dry, and separate texture, with grains typically being slimmer and longer compared to japonica rice.

Aromatic rice varieties, like basmati and jasmine, constitute a mere 1% of the world's rice production but are prized for their unique aroma, primarily due to the presence of 2-acetyl-1-pyrroline. The bulk of global rice production is comprised of glutinous rice varieties, encompassing both indica and japonica types.

(Merteens, 2006, Rokni, 2013, JungleDragon, n.d, OECD, 2004, Meertens, H.C.C., 2006,)

© Maundu, 2005

@Maundu 2005

Oryza glaberrima (African rice) is an annual grass plant that grows to a height of 0.6-1.2 m (shorter than many O. sativa varieties). Dryland types have simple, smooth culms with root formation at lower nodes and simple branching to the panicle. Floating types can branch and root at upper nodes. Panicles are stiff and compact with self-fertilizing flowers, but some cross-pollination occurs. African rice resembles Asian rice from a distance, but has smaller ligules, less panicle branching, and lacks lawns on spikelets. It is completely annual and dies after seeding.

Despite lower yields than O. sativa, this species possesses valuable traits like resistance to rice yellow mottle virus, African gall midge, and nematodes. It's also tolerant to drought, acidity, iron toxicity, and competes well with weeds. This suggests potential for crossbreeding with O. sativa to combine beneficial traits

(National Academies of Sciences, 1996, Nair, 2019).).

Rice varieties

Examples of Rice varieties in Kenya

"Sindano", highly susceptible to Rice Yellow Mottle Virus (RYMV) and "Basmati 217" highly susceptible to blast have been grown since the 1960s. Since then alternative varieties of both irrigated rice and rain fed rice have been identified.

Varieties of irrigated rice and their characteristics:

|

Variety |

Height in cm |

Maturity days |

Yield t/ha |

Cooking quality |

RYMW |

Blast |

|

"Basmati 217" |

118 |

122 |

4.6 |

Very good |

Resistant |

Susceptible |

|

"Basmati 370" |

118 |

122 |

5.3 |

Very good |

Resistant |

Susceptible |

|

"IR 2035-25-2" |

86.2 |

128 |

5.5 |

Good |

Moderately susceptible |

Moderately resistant |

|

"IR 2793-80-1" |

89 |

142 |

6.4 |

Good |

Susceptible |

|

|

"BW 96" |

68 |

135 |

9.0 |

Fair |

Susceptible |

Moderately resistant |

|

"UP 254" |

84.2 |

124 |

6.4 |

Good |

Moderately susceptible |

Moderately resistant |

|

"AD 9246" |

78.2 |

128 |

5.1 |

Good |

Moderately resistant |

Moderately susceptible |

|

"IR 19090" |

96.6 |

122 |

5.8 |

Good |

Moderately susceptible |

Moderately resistant |

|

Varieties for lowland (swampy) zones |

Varieties for upland (dry land) zones |

|

"Ci cong Ai" |

"Dourado Precose" |

|

"TGR 78" |

"2051 A 233/79" |

|

"IR 2793-80-1" |

"TGR 94" |

|

"BW 196" |

"WAB 181-18" |

|

"WaBis 675" |

"Nam ROO" |

|

|

"NERICA 1", "NERICA 4", "NERICA 10", "NERICA 11" |

The upland "NERICA" rice varieties were developed at the Africa Rice Center (AfricaRice) ex-WARDA. They are resistant to blast, RYMV stemborers and leafminers and are high yielding and doing well from West Africa to Uganda. They are now also being promoted by NIB (National Irrigation Board), Kenya, KALRO and JICA. In Kenya they have great potential for medium altitudes with high rainfall or possibility for irrigation. "NERICA" can be planted as other small grains, but do need irrigation especially during flowering, and fertilization.

Some characteristics of the NERICA varieties (KEPHIS).

|

Variety |

Optimal production altitude (masl) |

Maturity in days |

Gain yield (t/ha) |

Special attributes |

|

"NERICA 1" |

1500-1700 |

90-100 |

2.5-55 |

Aromatic, blast tolerant, long grains |

|

"NERICA 4" |

1500-1700 |

90-112 |

3.2-6.5 |

Blast tolerant, long grains |

|

"NERICA 10" |

1500-1700 |

86-93 |

3.5-6.7 |

Blast tolerant, long grains |

|

"NERICA 11" |

1500-1700 |

90-105 |

3.5 |

High rationing, tolerant to blast and drought, long grains |

|

NIBAM 110 |

1500-1700 |

110-120 |

3.0-5.0 |

Blast tolerant, RYMV tolerant, long grains, no anthocyanin |

|

IR_05N221 |

Irrigated and rain-fed lowland |

75-90 |

4.0-6.7 |

Tolerant to some blast and RYMV strains, good cooking qualities, good milling quality |

Varieties in Tanzania

• "Supa". Optimal production altitude: 0-400 m; grain yield: 1.5-3.5 t/ha; moderately resistant to RYMV and sheath rot.

• "IR 54". Optimal production altitude: 400-600 m; grain yield: 4.0-7.0 t/ha; moderately resistant to bacterial blight and sheath rot

• "IR 22". Optimal production altitude: 400-1000 m; grain yield: 6.6-8.0 t/ha; days to maturity: 120-13"5; resistant to bacterial blight.

• "Katrin". Optimal production altitude: 400-1000 m; grain yield: 6.6-8.0 t/ha; very low panicle shattering.

• "Dakawa". Optimal production altitude: 400-1000 m; grain yield: 3.5-5.2 t/ha; none-photoperiod sensitive; resistant to lodging except under high N levels; easy to thresh.

• "TXD 85". Optimal production altitude: 0-400 m; grain yield: 4.8-7.0 t/ha; moderately resistant to sheath rot, blast and RYMV.

• "TXD 88". Optimal production altitude: 0-400 m; grain yield: 2.8-6.5 t/ha; moderately resistant to sheath rot, blast and RYMV.

• "SARO 5". Optimal production altitude: 0-600 m; grain yield: 4.0-6.5 t/ha; susceptible to RYMV and sheath rot. Adapted to rain-fed lowlands and irrigated ecosystems.

• "Kalalu". Grain yield: 2-3 t/ha; resistant to RYMV and blast.

"Mwangaza". Grain yield: 2-3 t/ha; resistant to RYMV and blast.Ecological conditions

Ecological conditions

Rice thrives on land that is water saturated or even submerged during part or all of its growth. Optimal temperatures for rice growing are 20 to 37.7degC, and no growth occurs below 10oC. Optimal pH is between 5 and 7, though rice has been grown in fields with pH between 3 and 10. Rice will grow in altitudes ranging from 0 to 2500 m above sea level, but worldwide is mostly grown on the humid coastal lowlands and deltas. Aquatic rice may require a dependable supply of fresh, slowly moving water, at temperature of 21 to 29degC. Rain fed rice requires an average of 800 to 2000 mm of rainfall well distributed over the growing season. If rainfall is less than 1250 mm annually, irrigation is used to make up deficit. The crop is salt tolerant at some stages of growth; during germination but not seedling stages and has even been grown to reclaim salty soils. Terrain should be level enough to permit flooding, yet sloped enough to drain readily. The soils on which rice can grow are as varied as the climatic regime it tolerates, but ideally it prefers a friable loam overlying heavy clay, as in many coastal and delta areas.

Agronomic aspects

Seedling production.

Steps for producing healthy seedlings:

1. Seed selection. Select plump and healthy seeds.

2. Seed pretreatment. This is practiced in order to secure better germination of seeds and better growth of seedlings. It involves:

• Seed disinfection. Hot water treatment is effective in destroying the nematode Aphelenchoides besseyi, which causes the white tip disease. For more information on hot-water treatment click here

• Seed soaking. To supply the required moisture for germination, to shorten germination period and reduce seed rotting. During the soaking period change water to remove poisonous substances and allow entry of fresh air.

• Pre-sprouting. The seeds are drained and covered with grass for 24 to 48 hours. This ensures uniform seed germination, avoids over sprouting and allows air circulation for germination.

3. Sowing:

• Sowing 80 to 100 g/m2 is normal practice.

• Broadcast seed uniformly.

• Do not submerge the nursery bed after sowing.

• Use a seed rate of about 20 kg/acre (50 kg/ha).

4. Seed bed preparation (nursery):

• Plough at least 2 weeks before sowing and flooding.

• Puddle 1 week before sowing and prepare raised nursery bed

• Drain the nursery bed the day before sowing to stabilize the surface of the soil

• If the soil covering the nursery bed is too soft, sown grains are buried into the soil resulting in poor establishment.

• For 1 ha of transplanted rice, a nursery of about 350 m2 is required

• Irrigate a few days after sowing so that the surface is kept moist, and as the seedlings emerge keep submerged conditions with water controlled at 1 to 3 cm according to growth of seedling.

• Raise the water level to 10 cm one day before uprooting to ease washing off of soil that sticks to roots. This will make transplanting easy.

Main land preparation

a) Under irrigation: Land preparation is carried out by flooding the fields to a depth of 10 cm and then cultivating by use of tractor (40 to 75 hp) equipped with rotavators. Good timing and quality of land preparation will influence the growth of rice. Poor and untimely land preparation will cause serious weed problems and expose plants to harmful substances such as carbon dioxide and butyric acid, released by decaying organic matter in the soil.

It is recommended that land should be tilled and immediately flooded at least 15 days before transplanting or direct sowing. The purposes of this are:

• To save the seedling from the effect of high concentration of harmful substances generated by decomposing organic matter rotated into flooded soils.

• To prevent loss of nitrogen released by decomposing organic matter through denitrification. The ammonia released during decomposing of organic matter is conserved because ammonia is not converted to nitrate due to the absence of oxygen in the soil. This ammonia is later utilised by the rice plant.

b) Under rainfed situation: Land should be ploughed twice and harrowed once.

Transplanting

It is important to transplant from the nursery as soon as the seedlings are big enough. Seedlings are said to be ready for transplanting after a period of between 3 to 4 weeks depending on daylight, temperatures and the variety. "Basmati 217" will be ready for transplanting 25 days after sowing (4.5 to 5 leaf stage); "BW 196" and others at 28 to 30 days after sowing (5 to 5.5 leaf number).

Planting depth:

Practise shallow planting of about three cm depth for vigorous initial growth and will result in good rooting and tillering. Deep transplanting delays and reduces tillering resulting in a non-uniform crop growth and ripening, consequently resulting in yield losses. Seedlings should be transplanted in an upright position to allow correct tillering and rooting.

Direct sowing method: Trials have been done on direct sowing and have showed that the same level of yields performance as those of transplanting system can be obtained. This method saves substantially on labour input. However it has some disadvantages such as uneven germination rate and more weeding work in the paddy field.

Planting under rainfed conditions:

Planting should be done before the onset of the long rains. Farmers are advised to use certified seed and appropriate variety for the region. Drill seed in rows at the rate of 50 kg/ha with a spacing of 25 cm for short varieties and 35 cm for tall varieties. In case of broadcasting, 75 kg/ha is often used.

Main field water management

Water is applied to the rice field for the use of the rice plant and also for suppressing weed growth. For this reason, it is important to practise appropriate water management throughout the growing period of a rice crop.

In lowland rice fields, water comes from rainfall and irrigation. Water is lost by transpiration, evaporation, seepage and percolation. Prevent water loss by:

- Repairing levees to minimise seepage.

- Removal of weeds to avoid competition with rice plants for water.

- Increasing the height of levees to prevent surface run-off water.

Critical stages when water is required in large quantities are:

- For a period of 3 to 7 days after transplanting cover the crop up to 80% of its height. This reduces transpiration and gives the plants a chance to re-establish their roots to be able to take up enough water from the soil

- From the stage of booting to 14 days after heading, more water is required because the shedding of pollen and the process of fertilsation requires very high moisture content in the air. Low moisture content in the air leads to sterile spikelets.

Seven to 10 days before harvesting, drain the field to harden the soil for good harvesting and also to hasten the drying and ripening of the rice grains.

Harvest, post-harvest practices and markets

Harvest

Time from planting to harvesting varies between 4 to 6 months. The crop should be ready to harvest when 80% of the panicles are straw dust coloured and the grain in the lower portion are in the hard dough stage. In a well-grown crop, the grain matures evenly and can be harvested in one operation. In the tropics it is essential to harvest the crop on time, otherwise grain losses may result from feeding by rats, birds, insects and from shattering and lodging. When harvesting rice with a sickle or knife, cut the rice straw about 4-5 cm above the ground to minimize what's left standing. This prevents stem-borer worms and adults from completing their life cycle.

Post-harvest

After cutting the rice stems, they are bundled for transportation to the next stage.

• Drying: Rice grains typically contain a high moisture content of about 25% after harvest, which can result in discoloration and pest problems. To mitigate this, it's essential to reduce the moisture content to around 13-14%. This is achieved through either traditional sun drying or mechanical drying using specialized dryers. It is crucial to complete the drying process within 24 hours of harvesting to maintain grain quality.

• Threshing: Following drying, the next step is threshing, where the rice grains are separated from the husks. This can be done manually by hand or foot, involving swinging and beating actions against a frame, or with the help of winnowing machines.

• Cleaning: Once threshing is complete, the rice undergoes a cleaning process to remove any remaining impurities such as rice straw, chaff, foreign objects, and immature grains from the paddy. This meticulous cleaning ensures rice quality and reduces the risk of contaminants, thereby minimizing transportation and milling costs for growers. Additionally, it lowers machine wear and spoilage costs for rice mill operators.

• Milling: Rice milling is a critical post-harvest step where mechanical processes are employed to remove the outer layers of the rice grain, revealing the edible white kernel. By-products like the germ and bran can be repurposed for livestock feed.

• Final Drying: Before rice is stored, it undergoes a final drying process to reach a moisture content of approximately 12%. This step is essential to preserve the grain quality for storage and consumption.

• Storage: After completing these preparatory steps, the rice is ready for storage. Proper storage is crucial to maintain the quality and prevent deterioration. Rice should be stored in clean, airtight containers or silos to protect it from moisture, pests, and contaminants. Maintaining a consistent temperature and humidity level in the storage area is also vital to prevent spoilage and maintain rice quality over time(Wikifarmer, 2022a, JICA, 2004).

Markets

Rice is cultivated primarily for the grain, which is a main staple food in many countries, especially in Asia. In Kenya it is becoming increasingly popular, especially in urban centres. From 2010 to 2014, Kenya had a yearly production of about 119,000 metric tons (FAOSTAT, 2014). Consumption of wheat has been on a steady increase from 410,000 metric tons in 2010 to 564,000 metric tons in 2014 This increase in demand and the development of new upland varieties have created an opportunity for farmers to venture into rice growing. (Economic Review of Agriculture, 2015).

Nutritional value and recipes

White and brown rice are two of the most widely consumed rice types. The brown type is essentially the whole rice grain, comprising the bran, which is rich in fiber, the germ, packed with nutrients, and the endosperm, a source of carbohydrates. In contrast, white rice is produced by removing the bran and germ, leaving just the endosperm. It is then processed to enhance flavor, prolong shelf life, and improve its cooking characteristics.

Rice primarily is a source of carbohydrates, offering a quick and easily digestible energy source. Brown rice, in particular, is rich in dietary fiber, aiding digestion and promoting a feeling of fullness. Rice contains moderate amounts of protein, contributing to daily protein intake, although it is not as protein-rich as some other foods. It is also low in fat and cholesterol-free, making it a heart-healthy choice.

Rice provides essential vitamins and minerals, including B vitamins and minerals like magnesium, phosphorus, and selenium, which are crucial for metabolism and overall health. Additionally, rice, such as red and black varieties, can contain antioxidants like anthocyanins and flavonoids, offering potential health benefits and reducing the risk of chronic diseases.

Being gluten-free, rice is suitable for individuals with celiac disease or gluten sensitivity. Its versatility allows for easy incorporation into various cuisines and diets, and it holds cultural significance in many societies. Brown rice, with its higher fiber content and added nutrients, is generally considered a healthier option compared to white rice.

Note: White rice has a high glycemic index, causing notable blood sugar spikes after meals, which could elevate the risk of type 2 diabetes. To manage this risk, it's recommended to consume white rice in moderation. Combining it with fiber-rich foods, vegetables, and lean proteins can offset its glycemic impact and promote better blood sugar control.

(Healthline n.d, Medicalnewstoday)

Table 1: Proximate nutritional value of 100g of rice

Code Food Name |

Rice, white, milled, polished grain, dry, raw |

Rice, white, milled, polished grain, dry, boiled (without salt) |

Recommended daily allowance (approx.) for adults a |

Edible conversion factor |

1 |

||

Energy (kJ) |

1500 |

503 |

9623 |

Energy (kcal) |

353 |

119 |

2300 |

Water (g) |

12.2 |

70.5 |

2000-3000c |

Protein (g) |

7.6 |

2.6 |

50 |

Fat (g) |

1 |

0.3 |

<30 (male), <20 (female)b |

Carbohydrate available (g) |

78.1 |

26.2 |

225 -325g |

Fibre (g) |

0.7 |

0.2 |

30d |

Ash (g) |

0.4 |

0.2 |

|

Minerals |

|||

Ca (mg) |

21 |

9 |

800 |

Fe (mg) |

0.9 |

0.3 |

14 |

Mg (mg) |

23 |

8 |

300 |

P (mg) |

144 |

48 |

800 |

K (mg) |

59 |

20 |

4,700f |

Na (mg) |

17 |

8 |

<2300e |

Zn (mg) |

1.32 |

0.44 |

15 |

Se (mcg) |

1 |

0 |

30 |

Bioctive compounds. |

|||

Vit A RAE (mcg) |

0 |

0 |

800 |

Vit A RE (mcg) |

0 |

0 |

800 |

Retinol (mcg) |

0 |

0 |

1000 |

b-carotene |

0 |

0 |

600 – 1500g |

Thiamin (mg) |

0.07 |

0.02 |

1.4 |

Riboflavin (mg) |

0.11 |

0.04 |

1.6 |

Niacin (mg) |

1.1 |

0.4 |

18 |

Dietary Folate Eq. (mcg) |

[9] |

2 |

400f |

Food folate (mcg) |

[9] |

2 |

400f |

Vit B12 (mg) |

0 |

0 |

3 |

Vit C (mg) |

0 |

0 |

60 |

Source (Nutrient data): FAO/Government of Kenya. 2018. Kenya Food Composition Tables. Nairobi, 254 pp. http://www.fao.org/3/I9120EN/i9120en.pdf

RE=retinol equivalents.

RAE =Retinol activity equivalents. A RAE is defined as 1μg all-trans-retinol, 12μg beta-carotene, or 24μg α-carotene or β-cryptoxanthin.

a Lewis, J. 2019. Codex nutrient reference values. Rome. FAO and WHO

b NHS (refers to saturated fat)

c https://www.hsph.harvard.edu/nutritionsource/water/

d British Heart Foundation

e FDA

f NIH

g Mayo Clinic

Nutritive Value per 100 g of edible Portion

| Raw or Cooked Rice | Food Energy (Calories / %Daily Value*) |

Carbohydrates (g /%DV) |

Fat (g / %DV) |

Protein (g / %DV) |

Calcium (g / %DV) |

Phosphorus (mg / %DV) |

Iron (mg / %DV) |

Potassium (mg / %DV) |

Vitamin A (I.U) |

Vitamin C (I.U) |

Vitamin B 6 (I.U) |

Vitamin B 12 (I.U) |

Thiamine (mg / %DV) |

Riboflavin (mg / %DV) |

Ash (g / %DV) |

| Brown Rice, long-grain, cooked | 111 / 6% | 23.0 / 8% | 0.9 / 1% | 2.6 / 5% | 10.0 / 1% | 83.0 / 8% | 0.4 / 2% | 43.0 / 1% | 0.0 IU / 0% | 0.0 / 0% | 0.1 / 7% | 0.0 / 0% | 0.1 / 6% | 0.0 / 1% | 0.5 |

| Brown Rice, medium-grain, cooked | 112.0 / 6% | 23.5 / 8% | 0.8 / 1% | 2.3 / 5% | 10.0 / 1% | 77.0 / 8% | 0.5 / 3% | 79.0 / 2% | 0.0 IU / 0% | 0.0 / 0% | 0.1 / 7% | 0.0 / 0% | 0.1 / 7% | 0.0 / 1% | 0.4 |

| White Rice, glutinous, cooked | 97.0 / 5% | 21.1 / 7% | 0.2 / 0% | 2.0 / 4% | 2.0 / 0% | 8.0 / 1% | 0.1 / 1% | 10.0 / 1% | 0.0 IU / 0% | 0.0 / 0% | 0.0 / 1% | 0.0 / 0% | 0.0 / 1% | 0.0 / 1% | 0.1 |

| White Rice, long-grain, regular, cooked | 130 / 7% | 28.2 / 9% | 0.3 / 0% | 2.7 / 5% | 10.0 / 1% | 43.0 / 4% | 1.2 / 7% | 35.0 / 1% | 0.0 IU / 0% | 0.0 / 0% | 0.1 / 5% | 0.0 / 0% | 0.2 / 11% | 0.0 / 1% | 0.4 |

| White Rice, medium-grain, cooked | 130 / 7% | 28.6 / 10% | 0.2 / 0% | 2.4 / 5% | 3.0 / 0% | 37.0 / 4% | 1.5 / 8% | 29.0 / 1% | 0.0 IU / 0% | 0.0 / 0% | 0.1 / 3% | 0.0 / 0% | 0.2 / 11% | 0.0 / 0% | 0.2 |

| White Rice, short-grain, cooked | 130 / 7% | 28.7 / 10% | 0.2 / 0% | 2.4 / 5% | 1.0 / 0% | 33.0 / 3% | 26.0 / 1% | 1.5 / 8% | 0.0 IU / 0% | 0.0 / 0% | 0.1 / 3% | 0.0 / 0% | 0.2 / 11% | 0.0 / 1% | 0.2 |

| Rice Bran crude | 316.0 / 16% | 49.7 / 17% | 20.8 / 32% | 13.3 / 27% | 57.0 / 6% | 1677 / 168% | 18.5 / 103% | 1485 / 42% | 0.0 IU / 0% | 0.0 / 0% | 4.1 / 203% | 0.0 / 0% | 2.8 / 184% | 0.3 / 17% | 10.0 |

| Brown Rice Flour | 363 / 18% | 76.5 / 25% | 2.8 / 4% | 7.2 / 14% | 11.0 / 1% | 337 / 34% | 2.0 / 11% | 289.0 / 8% | 0 IU / 0% | 0.0 / 0% | 0.7 / 37% | 0.0 / 0% | 0.4 / 30% | 0.1 / 5% | 1.5 |

| White Rice Flour | 366.0 / 18% | 80.1 / 27% | 1.4 / 2% | 5.9 / 12% | 10.0 / 1% | 98.0 / 10% | 0.4 / 2% | 76.0 / 2% | 0.0 IU / 0% | 0.0 / 0% | 0.4 / 22% | 0.0 / 0% | 0.1 / 9% | 0.0 / 1% | 0.6 |

| Wild Rice cooked | 101 / 5% | 21.3 / 7% | 0.3 / 1% | 4.0 / 8% | 3.0 / 0% | 82.0 / 8% | 0.6 / 3% | 101 / 3% | 3.0 IU / 0% | 0.0 / 0% | 0.1 / 7% | 0.0 / 0% | 0.1 / 3% | 0.1 / 5% | 0.4 |

*Percent Daily Values (DV) are based on a 2000 calorie diet. Your daily values may be higher or lower, depending on your calorie needs.

Recipes

1. Couscous

West Africa

Note: Couscous is a steamed granulated product made from cereal flour)

Ingredients

10 cups hungry rice flour

1 heaped teaspoon dry baobab leaf or dry okro powder

Water for mixing and steaming

Procedure

Sieve flour with 1mm sieve to ensure an adequately fine starter product

Pour flour in a bowl and sprinkle with about 2 cups cold water, mix and rub wetted flour between both palms to form sand-like aggregates

Prepare the steamer for steaming

Sieve the granulated product with a 1.5 mm mesh sieve

Put the sieved cereal granules on the top part of the double boiler (steamer/ couscoussier) and steam for 15 minutes

Take out the steamed granules which should now form a single mass, put into a convenient bowl and break it up into particles again

Put the granules back into the steamer and steam for another 15 minutes

Take out again the formed mass and break up into aggregates, sieve the resulting particles with a 2.5 mm sieve

If for later consumption (storage), sun dry the sieved cereal granules until grains are no longer moist to touch, then store in a tight lidded container

For immediate consumption, sprinkle sieved granules with 3½ to 4 cups water and mix thoroughly with the fingers, add one heaped teaspoon of baobab* leaf powder or dry okro powder, mix thoroughly again

Put mixture back in the steamer and steam again for 15 minutes

Cool cooked couscous slowly and serve warm with peanut soup or couscous sauce

Yields 8 servings

Remarks

*Powdered dry baobab leaf (Adansonia digitata or dry okro powder is used locally used to prevent the cereal granules from sticking together during the final steaming process. Where these are not available, a teaspoon of peanut oil or any light cooking oil, or a blob of margarine will produce the same effect.

Millet, sorghum and maize can be a substitute for Hungry rice

2. District and region: Coast

Food name (in local language and other languages)

Pea pilau

Ingredients (with quantities and/or proportions):

2 cups of rice

1 cup of garden peas

2 medium sized Irish potatoes

2 medium sized onions

½ cup of ghee

2 cloves

Crushed garlic

2 pieces of cinnamon

½ tsp turmeric powder

1 cardamom

1 tsp cumin seeds

Procedure (step by step explanation with time):

• Pick the rice and wash it and peel the potatoes

• Pound the cinnamon, cardamom and cumin together in a mortar

• Heat the fat and fry the onions until light brown

• Add all the spices and cook for 10 minutes

• Stir well; add Irish potatoes, peas and salt. Continue frying for a while

• Add the rice and fry lightly for 5 minutes

• Pour in 4 cups of water, cover and simmer until rice is cooked

• Serve warm

Served with: Kachumbari

| African gall midge (Orseolia oryzivora) It is a small reddish-brown midge (similar to a mosquito) 4 to 5 mm long. Females lay up to 300 eggs on rice leaf sheaths. Upon hatching, the small maggots wiggle down to the leaf blade and move between the leaf sheath and the stem until the growing points where they feed for 2 to 3 weeks. Larval feeding induces development of light swellings or galls, which are inconspicuous until larvae are ready to pupate. The galls are long cylindrical, about 3 mm in diameter and from a few cm up to 1 to 1.5 m long. They are often silvery white and resemble an onion leaf, hence they are generally known as 'silver shoots' or 'onion leaf galls'. Galls generally appear about 20 to 40 days after the crop has been transplanted. Gall midges can cause serious damage from the seedling stage to panicle initiation. Attacked tillers do not produce panicles. Galled plants may tiller profusely to compensate for loss of growing points. A serious attack results in stunted plant growth and poor yields. Gall midges do not attack rice plants that have matured beyond tillering stage. These midges spent some generations on wild grasses and then move to attack young rice plants. They are pests during the rainy season, and are most serious on rain-fed lowland and irrigated rice.

What to do:

|

| Stink bugs produce a strong odour when disturbed. Adult Aspavia bugs are brown bugs with a large triangular shield on the back having three yellow spots and a spine at each side of the thorax. Nezera viridula is green and about 1.2 cm long. Alydid bugs have a long slender body and lack a triangular shield on the back. Riptortus is stout and varies from light to dark brown; the hind legs are enlarged. Both nymphs and adult bugs feed sucking rice grains in the milky stage. When grains have ripened the bugs feed on panicle stalks and pedicels. Riptortus bugs also feed on hard dough rice grains. Bug feeding causes pecky rice that is partially or wholly stained due to infections with bacteria and fungi. The glumes change colour first to light brown, then darker and may turn grey in severe cases. Damage grains are shrivelled and unfilled. Severity of the damage depends on the stage of grain development and on the number of punctures in the grain.

What to do:

|

| Storage pests (Sitophilus oryzae, Rhyzopertha dominica) The most serious pests of stored rice are the rice weevils (Sitophilus oryzae) and the lesser grain-borer (Rhyzopertha dominica). Good store hygiene plays an important role in limiting infestation by rice weevil.

What to do:

|

| Rice root-knot nematode (Meloidogyne graminicola) Symptoms consist of characteristic hooked-like galls on roots, newly emerged leaves appear distorted and crinkled along the margins, and infested plants are stunted and yellow. Heavily infested plants flower and mature early. The rice root-knot nematode is a damaging parasite on upland, lowland and deepwater rice. It is well adapted to flooded conditions and can survive in waterlogged soil as eggs in egg-masses or as juveniles for long periods. Numbers of nematodes decline rapidly after 4 months but some egg masses can remain viable for at least 14 months in waterlogged soil. This root-knot nematode can also survive in soil flooded to a depth of one m for at least 5 months. It cannot invade rice in flooded conditions but quickly invades when infested soils are drained. It can survive in roots of infected plants. It prefers soil moisture of 32%. It develops best in moisture of 20% to 30% and soil dryness at rice tillering and panicle initiation. Its population increases with the growth of susceptible rice plants.

What to do:

|

| White tip nematode (Aphelenchoides besseyi) Rice is the most important host worldwide. Other host plants include; strawberry, onion, garlic, sweet corn, sweet potato, soybean, sugar cane, horseradish, lettuce, millet, many grasses, orchids, chrysanthemum, marigold, Mexican sunflower, African violets, and rubber plant (Hibiscus brachenridgii). Feeding of the nematodes at leaf tips in rice results in whitening of the top 3 to 5 cm of the leaf leading to necrosis (described as "White Tip" of rice). There is also distortion of the flag leaf that encloses the panicle. Diseased plants are stunted, lack vigour and produce small panicles. Affected panicles show high sterility, distorted glumes and small and distorted kernels.

What to do:

|

| African armyworm (Spodoptera exempta) Armyworms may cause severe defoliation in upland rice plants leaving only the stem. Armyworms are regarded as occasional pests, but during an outbreak they devastate rice crops. What to do:

|

| Several species of stemborers attack rice. The more important are the striped borer (Chilo partellus), Chilo zacconius, Chilo orichalcocilielus, the white rice borer (Maliarpha separatella), the yellow borer (Scirpophaga sp.) and the pink stemborer (Sesamia calamistis). The caterpillars bore into the stem of rice plants. Caterpillars of the yellow borer bore into the stem below the growing point, destroying tillers. The white borer and the pink stemborer attack rice at full tillering stage preventing grains from filling up and ripening. This damage results in empty panicles known as "whiteheads". The striped borer feed on rice plants at all stages. Young caterpillars cause "dead hearts". What to do:

|

| Stalk-eyed shoot flies (Diopsis spp.) The dark brown flies are about 8 mm in length, and have the eyes situated on 2 long stalks projecting from both sides of the head. Flies lay eggs singly on the upper surface of young leaves, or on the leaf sheath of older plants. The whitish maggots that hatch from the eggs penetrate into the growing zone (heart) of the plant. As a result of maggot feeding the central whorl does not open, but dries-up and dies, producing what is commonly known as "dead heart". Maggots move readily from one tiller to another. One maggot can destroy up to 10 neighbouring tillers. Later generations feed on the developing flower head. Pupation normally occurs in the first 3 leaf sheath of healthy tillers, generally one pupa per tiller. A severe attack is likely to occur when water levels are low. Such attacks reduce yields of rice plants. Shoot fly attack rice plants early in the crop growth stage, shortly after emergence in direct-seeded fields or shortly after transplanting. They are present throughout the crop growth period, although infestation is low in the flowering-ripening stages.

What to do:

|

| Case worm (Nymphula depunctalis - Parapoynx stagnalis) The case worm is a common pest on wetland rice. Moths are small (1 to 1.2 cm in wingspan) with white markings and black specks on the wings. Females lay eggs in small batches (about 20) on the lower side of leaves that are floating on the water surface. Upon hatching caterpillars are yellow to green with light brown heads. They climb onto a leaf and begin feeding by scrapping the leaf surface causing linear grazing of leaves giving the leaf tissue a ladder-like appearance. Later caterpillars cut a piece of rice leaf, roll it up into a case and seal the edges with silk material leaving the interior end open. The cut near the tip of a leaf is characteristic. At all times the caterpillar is likely to be partly or wholly enclosed in its portable leaf case. The caterpillar attacks the food plant only in the vegetative stage, during the first 4 weeks after transplanting. Caterpillars of the case worm are semi-aquatic, ascending the plants at night to feed. Heavy infestation on small seedlings may completely destroy a rice crop. Damaged plants may recover but crop maturation may be delayed about a week. Yield loss may occur when the caseworm occurs in combination with other non-defoliating insects such as whorl maggots and stemborers. Damaged plants are stunted and produce fewer tillers.

What to do:

|

| Termites, also known as white ants are common pests of upland rice in West Africa where they may cause serious damage during dry periods. They may also occur in lowland areas in light texture soils. They generally attack plants in their later growth stage by hollowing out their root system and filling it with soil resulting in the lodging of the rice plants. The attacked plants are then predisposed to further damage by ground-dwelling pests such as rodents, ants, and secondary infection by fungi and bacteria. Damaged plants can easily be pulled up by hand because the roots are severed.

What to do:

|

| Hispid beetles (Trichispa spp., Dicladispa viridicyanea, Dactylispa bayoni) Hispid beetles are serious pests of rice in some countries in Africa, causing severe defoliation and as vectors of the Rice Yellow Mottle Virus. Adult beetles have numerous spines on thorax and abdomen. Trichispa sericea is the most common of the hispid beetles. The adult is a dark grey beetle covered with spines, and about 3 to 4 mm long. Females lay eggs singly in slits made under the epidermis of the upper portion of the leaf. Eggs are white, boat-shaped and about 1 mm long. Upon hatching, the grubs (larvae) mine within the leaf. Grubs are slender, yellow and about six mm long. They pupate in the mine. When infested leaves are held against the light, the grub or pupa may be seen as a dark spot in the mine. Hispid beetles attack the crop in the early growth stages. Larval feeding occurs during the tillering stage. The first attack in a field is highly localised, but the infested area spreads rapidly. Feeding by adults on the leaves causes characteristic narrow white streaks or feeding scars that run along the long axis of the leaf. Mining by grubs within the leaf shows as irregular pale brown blister-like patches. Feeding results in loss of chlorophyll and the plants wither and die. The most serious damage occurs in nurseries, which may be completely destroyed. Severe infestations sporadically occur on transplanted rice and can kill the plant. When the plants survive, they usually recuperate and produce some grain. However, damaged plants often mature late. Hispid beetles are prevalent in wetland environments, especially irrigated lowland fields. They are generally most abundant during the rainy season.

What to do:

|

| Flea beetles (Chaetocnema spp.) Flea beetles make small holes in the leaf when feeding, however, this damage is considered minor. Most important, these beetles are potential vectors of the Rice Yellow Mottle Virus. Flea beetles are small, and have enlarged hind legs and jump when disturbed.

What to do:

|

| Rice whorl maggots (rice leafminers) (Hydrellia spp.) The rice whorl maggot (Hydrellia prosternalis) has been reported from West Africa. Another species Hydrellia sp. has been reported in Kenya (NIB, 1995). Adults of the rice whorl maggot and rice leafminers are small flies (1.5 to 3 mm long), grey to black in colour with silvery white or golden brown markings on the lower part of the head. They lay white cigar-shaped eggs on the leaves. Upon hatching the maggots of the leafminers penetrate the leaf tissue and feed in between the 2 layers of the leaf causing mines parallel to the veins. Maggots may pupate in an existing mine or migrate to a different leaf to form a new mine. High humidity (80-100% relative humidity) is required for leafminer development, therefore, mines are typically observed in leaves close or lying on the water surface. Whorl maggots start feeding on the leaf margins causing large scarred areas giving the leaf a ragged appearance and causing eventual leaf collapse. Eventually the maggots enter the whorl and tunnel the plant's developing stem.

Feeding damage by leafminers retards plant development, reduces plant vigour and renders infested plants less competitive with weeds. Plant vigour and weather conditions affect the extent and seriousness of the damage caused by the rice leafminer. Damage extent is closely related to the speed the plant growths erect and out of the water. Any factor affecting plant growth, which increases the number of leaves remaining lying on the water, or the length of time they are fully in contact with water will increase damage. The plant is usually able to produce additional leaves, but continued mining can result in reduced tillering, greater susceptibility to later pest attack, delayed maturity, or death of the plant. Once leaves start growing upright above the water, the rice leafminer does not cause economic damage. Attack by the whorl maggot may kill young plants (2 to 6 weeks after emergence) depending on the severity of the damage. Plants that survived damage are eventually drowned by the flood, or plant stands get so thinned that are easily overwhelmed by weeds. Other leaf-mining fly (Creodont orbiting) has been reported as a minor pest in West Africa. This leaf-mining fly is widely spread in the rice-growing region in Ghana, but it is of no apparent economic importance. The adult is a small fly (about 1.6 mm long). Females lay eggs into the leaf tissue, and the maggots feed forming mines towards the leaf tip. Maggots pupate within the mines. Symptoms of damage are the transparent, light brown mines that are elongated along one side of the midrib reaching up to 6 cm in length.

What to do:

|

Information on Diseases

The most serious diseases of rice are: Rice blast disease (Magnaporthe grisea) and Bacterial leaf blight (Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae).

Other diseases of economic importance include Brown Leaf Spot (Bipolaris oryzae), Rice Yellow Mottle Virus (Sobemovirus) and White Tip Disease (nematode - Aphelenchoides besseyi).

Examples of Rice Diseases and Organic Control Methods

| Failure of seedlings to emerge is the most obvious symptom of seed rot and pre-emergence damping off. Examination may reveal a cottony growth of mycelium (mould) in and around seed coats and the emerging seedlings, indicating attack by water mould(s). The growing point or root of germinated seedlings has a dark brown discolouration or rot. The base of the leaf sheath and the roots of emerged seedlings have a similar dark brown or reddish-brown rot. Affected seedlings appear stunted and yellow and may soon wither and die (seedling blight). Water moulds are particularly severe in water-seeded rice culture. In areas where fields are frequently water-seeded, it has become difficult to obtain adequately dense and uniform stands. Seed rots caused by the water moulds Pythium and Achlya, and to a lesser extent by the fungus Fusarium, have been identified as the causes of the problem. These fungi often act as a complex within affected fields. Symptoms of water mould can be observed through the flood water as balls of fungal strands radiating from seeds on the soil surface. When the water is removed using the critical point method of water-seeding, affected seeds are surrounded by a mass of fungal strands. This results in circular, copper brown or dark green spots on the soil surface, about the size of a penny, with the rotted seed at the centre. The colours of the spots are the result of bacterial and algal growth. Seed rot by water moulds is favoured when the water temperature is unusually high or low. If seedlings are attacked after germination at pegging, seedlings become yellow and stunted and grow poorly.

What to do:

|

| Bacterial leaf blight (Xanthomonas oryza pv. oryza) The first symptom of the disease is a water soaked lesion on the edges of the leaf blades near the leaf tip. The lesions expand and turn yellowish and eventually greyish-white and the leaf dries up. High rainfall with strong winds provides conditions for the bacteria to multiply and enter the leaf through injured tissue. What to do:

|

| Blast (Pyricularia oryzae (Magnaporthe grisea) This disease can cause serious losses to susceptible varieties during periods of blast favourable weather. Depending on the part of the plant affected, the disease is often called leaf blast, rotten neck, or panicle blast. The fungus produces spots or lesions on leaves, nodes, panicles, and collar of the flag leaves. Leaf lesions range from somewhat diamond-shaped to elongated with tapered, pointed ends. The centre of the spot is usually grey and the margin brown or reddish-brown. Both the shape and colour of the spots may vary and resemble those of the brown leaf spot disease. Blast differs from brown leaf spot in that it causes longer lesions and develops more rapidly.

The blast fungus frequently attacks nodes at the base of the panicle and the branches of the panicle. If the panicle is attacked early in its development, the grain on the lower portion of the panicle may be blank giving the head a bleached whitish colour, giving the name "blasted" head or rice "blast". If the node at the base of the panicle is infected, the panicle breaks causing the "rotten neck" condition. In addition, the fungus may also attack the nodes or joints of the stem. When a node is infected, the sheath tissue rots and the part of the stem above the point of infection often is killed. In some cases, the node is weakened to the extent that the stem will break causing extensive lodging. Blast generally occurs scattered throughout a field rather than in a localised area of the field. Late planting, frequent showers, overcast skies, and warm weather favour development of blast. Spores of the fungus are produced in great abundance on blast lesions and can become airborne, disseminating the fungus a considerable distance. High nitrogen fertilisation should be avoided in areas that have a history of blast.

What to do:

|

| Brown leaf spot (Bipolaris oryzae) This disease was previously called Helminthosporium leaf spot. Most conspicuous symptoms of the disease occur on leaves and glumes of maturing plants. Symptoms also appear on young seedlings and the panicle branches in older plants. Brown leaf spot is a seed-borne disease. Leaf spots may be evident shortly after seedling emergence and continue to develop until maturity.

Leaf spots vary in size and are circular to oval in shape. The smaller spots are dark brown to reddish brown, and the larger spots have a dark-brown margin and reddish brown to grey centres. Damage from brown spot is particularly noticeable when the crop is produced in nutritionally deficient or otherwise unfavourable soil conditions. Significant development of brown spot is often indicative of a soil fertility problem.

What to do:

|

| Rice Yellow Mottle Virus (RYMV) (Sobemovirus) Rice yellow mottle virus is endemic in Africa, was first reported in Kenya in 1966, but is now known to occur in almost all irrigated rice growing areas in Africa. This disease can cause up to 92% yield loss on "Super", the most popular rice variety in Tanzania.

RYMV causes severe infections mainly in irrigated rice and is transmitted by beetles (Sesselia pusilla, Chaetocnema pulla, Trichispa sericea and Dicladispa viridicyanea) and mechanically. It is not seed transmitted.

Major symptoms of the disease are yellowing of leaves, stunting of affected plants, reduced tillering of the affected plants and sterility of the seed/grain.

What to do:

|

References and information links

References

- AIC (2002). Field Crops Technical Handbook.

- Acland J.D. (1980). East African Crops. An introduction to the production of field and plantation crops in Kenya, Tanzania and Uganda. FAO/Longman. ISBN: 0 582 60301 3.

- Africa Rice www.africarice.org

- Africa museums. Oryza sativa L. https://www.africamuseum.be/en/research/collections_libraries/biology/prelude/view_plant?pi=09290&cat=&cur_page=2

- Anthony Youdeowei (2002). Integrated Pest Management Practices for the Production of Cereals and Pulses. Integrated Pest Management Extension Guide 2. Ministry of Food and Agriculture (MOFA) Plant Protection and Regulatory Services Directorate (PPRSD), Ghana, with German Development Cooperation (GTZ). ISBN: 9988 0 1086 9.

- Bohlen, E. (1973). Crop pests in Tanzania and their control. Federal Agency for Economic Cooperation (bfe). Verlag Paul Parey. ISBN: 3-489-64826-9.

- Brunt, A.A., Crabtree, K., Dallwitz, M.J., Gibbs, A.J., Watson, L., Zurcher, E.J. (Eds.) (1996 onwards). Plant Viruses Online: Descriptions and Lists from the VIDE Database. Version: 20th August 1996. www.uidaho.edu

- Beye, A. M. and Guei, R. G. (2001). Rice Seed Production by Farmers: A Practical Guide. ISBN: 92-9113212-8. www.warda.org

- CABI International (2005). Crop Protection Compendium, 2005 Edition. Wallingford, UK www.cabi.org

- lwell, H, Maas, A. (1995). Natural Pest & Disease Control. Natural Farming network, Zimbabwe. The Plant Protection Improvement Programme and The Natural Farming Network.

- Heinrich, E. A., Barrion, A. T. (2004). Rice-feeding insects and selected natural enemies in West Africa: biology, ecology and identification. Los Banos (Philippines): International Rice Research Institute (IRRI), and Adbijan (Cote d'Ivoire) WARDA- The Africa Rice Center. ISBN 971-22-0190-2.

- Hossain, S. M. M., Mian, I. H., Islam, A. T. M. S. and Haque, M. M. (1999). Organic amendments of soil to control rice root-knot nematode (Meloidogyne graminicola). Bangladesh Journal of Scientific and Industrial Research. vol. 34, no 3-4, pp. 385-390 . ISSN 0304-9809 . INIST-CNRS, Cote INIST : 13166, 35400012026135.0140

- Information relating to rice research for development in Africa www.africarice.org

- International Rice Research Institute (2006). www.knowledgebank.irri.org

- Jones M. P., M. Dingkuhn, G. K. Aluko, and M. Semon, 1997. Interspecific Oryza sativa L. X O. glaberrima Steud. progenies in upland rice improvement. Euphytica, 92: 237-246.

- Jones M.P. (ed.), Dingkuhn M. (ed.), Johnson D.E. (ed.), Fagade S.O. (ed.) 1997. Interspecific hybridization : progress and prospects : proceedings of the workshop : Africa/Asia joint research on interspecific hybridization between the African and Asian rice species (O. glaberrima and O. sativa). WARDA. ISBN 92-9113-113-X

- LSU AgCenter. First Report of Whorl Maggots in Rice. February 2, 2005, SPDN Network News. By Boris Castro.

- Layton B. (2004). Bug Wise. www.msucares.com

- Mississippi State University Extension Service (2001): Rice diseases. www.msucares.com

- National Research Council. 1996. Lost Crops of Africa: Volume I: Grains. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. Available online: www.nap.edu

- NEMAPLEX (2007). Aphelenchoides besseyi. www.nemaplex.ucdavis.edu

- NERICA Compedium www.africarice.org

- NIB (1995). Mwea Rice Production Manual.

- Nutrition Data www.nutritiondata.com.

- Nwilene, F.E.; Nwanze, K.F. and Okhidievbie, O. (2006). African Rice Gall Midge: Biology, Ecology and Control. Africa Rice Center (WARDA) ISBN 92 9113 236 5 (PDF); ISBN 92 9113 255 1

- Nwilene, F.E; Agunbiade, T.A.; Togola, M.A. and Youm, O. (2008). Efficacy of traditional practices and botanicals for the control of termites on rice at Ikenne, southwest Nigeria. International Journal of Tropical Insect Science Vol. 28, No. 1, pp. 37-44. www.journals.cambridge.org

- Nyambo, B. (2001). Integrated Pest Management Plan for SOFRAIP. Soil Fertility Recapitalization and Agricultural Intensification Project. SOFRAIP. Ministry of Agriculture and Food Security, Tanzania.

- OISAT: Organisation for Non-Chemical Pest Management in the Tropics. www.oisat.org

- Oduro K.A. (2000). Checklist of Plant Diseases in Ghana. Vol. 1: Diseases. Ministry of Food and Agriculture. Plant Protection & regulatory Services Directorate, Ghana

- Rice insect guide

- Rice organic cultivation guide, Naturland 2002. Available also online www.naturland.de/en

- Texas A & M University (1996). Texas Plant Disease Handbook

- UC IPM Online. Statewide-Integrated Pest Management Program. How to manage pests, UC Pest Management Guidelines. Rice leafminer. www.ipm.ucdavis.edu

- Meertens, H.C.C., 2006. Oryza sativa L. In: Brink, M. & Belay, G. (Editors). PROTA (Plant Resources of Tropical Africa / Ressources végétales de l’Afrique tropicale), Wageningen, Netherlands. Accessed 25 August 2023.

- Rokni, S. (2013, November 21). Oryza sativa: A Résumé of Rice. Tropical Biodiversity. https://blogs.reading.ac.uk/tropical-biodiversity/2013/12/oryza-sativa-a-resume-of-rice/

- JungleDragon. (n.d.). Asian rice (Oryza sativa) JungleDragon. https://www.jungledragon.com/specie/577/asian_rice.html

- OECD (2004). (n.d.). Rice (Oryza sativa). https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/sites/dd5429dc-en/index.html?itemId=/content/component/dd5429dc-en

- Nair, K. P. (2019). Utilizing crop wild relatives to combat global warming. Advances in Agronomy, 153, 175-258.

- Wikifarmer. (2022a). Rice harvesting, yield per hectare and storage. Wikifarmer. https://wikifarmer.com/rice-harvesting-yield-per-hectare-and-storage/

Information links

• https://www.healthline.com/nutrition/is-white-rice-bad-for-you#nutrition

• https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/318699#benefits-of-brown-rice