|

African Cassava Mosaic Disease (ACMD) African cassava mosaic disease is one of the most serious and widespread diseases throughout cassava growing areas in Africa, causing yield reductions of up to 90%. It is spread through infected cuttings and by whiteflies (Bemisia tabaci).

Symptoms occur as characteristic leaf mosaic patterns that affect discrete areas and are determined at an early stage of leaf development. Symptoms vary from leaf to leaf, shoot to shoot and plant to plant, even of the same variety and virus strain in the same locality. Some leaves situated between affected ones may seem normal and give the appearance of recovery. |

|

|

What to do:

|

|

Anthracnose (Glomerella manihotis) Initial symptoms of the disease are oval lesions ("sores") on young stems. On older stems, raised fibrous lesions develop that eventually become sunken.

|

|

|

What to do:

|

|

Birds and other vertebrate pests Birds, rodents, monkeys, pigs and domestic animals (cattle, goat and sheep) are common vertebrate pests of cassava.

Measures that help to manage damage by these pests include: |

|

|

What to do:

|

|

Brown leaf spot (Cercosporidium henningsii) Symptoms are restricted to older leaves. Brownish round spots with definite borders appear on the upper leaf surface. On the lower leaf surface, they are brownish-grey in colour. Infected leaves later become yellow and eventually drop. In wet areas the disease may cause a yield reduction of up to 20%. |

|

|

What to do:

|

|

Cassava bacterial blight (Xanthomonas campestris pv. manihotis) It is a major constraint to cassava cultivation in Africa. Infected leaves show localised, angular, water-soaked areas. Under severe disease attack heavy defoliation occurs, leaving bare stems, referred to as "candle sticks". Since the disease is systemic, infected stems and roots show brownish discolouration. During periods of high humidity, bacterial exudation (appears as gum) can readily be observed on the lower leaf surfaces of infected leaves and on the petioles and stems. The disease is favoured by wet conditions. This disease is primarily spread by infected cuttings. It can also be mechanically transmitted by raindrops, use of contaminated farm tools (e.g. knives), chewing insects (e.g. grasshoppers) and movement of man and animals through plantations, especially during or after rain. Yield loss due to the disease may range from 20 to 100% depending on variety, bacterial strain and environmental conditions. |

|

|

What to do:

|

|

Cassava brown streak virus disease (Potyvirus - Potyviridae) It is particularly serious in coastal areas of Kenya, Zanzibar, Mozambique and Tanzania and lakeshore region of Malawi and in Uganda and is a threat to the whole of sub-Saharan Africa. The virus is vectored by whiteflies (Bemisia spp.) and also transmitted through infected cuttings. Symptoms include yellowing (leaf chlorosis) and brown streaks in the stem bark (cortex). Infected tubers have brown streaks (root necrosis) (Field Crops Technical Handbook, MoA, Kenya). It's a stealth virus, which destroys everything in the field. The leaves may appear healthy even when the roots have rotted away.

|

|

|

What to do:

|

|

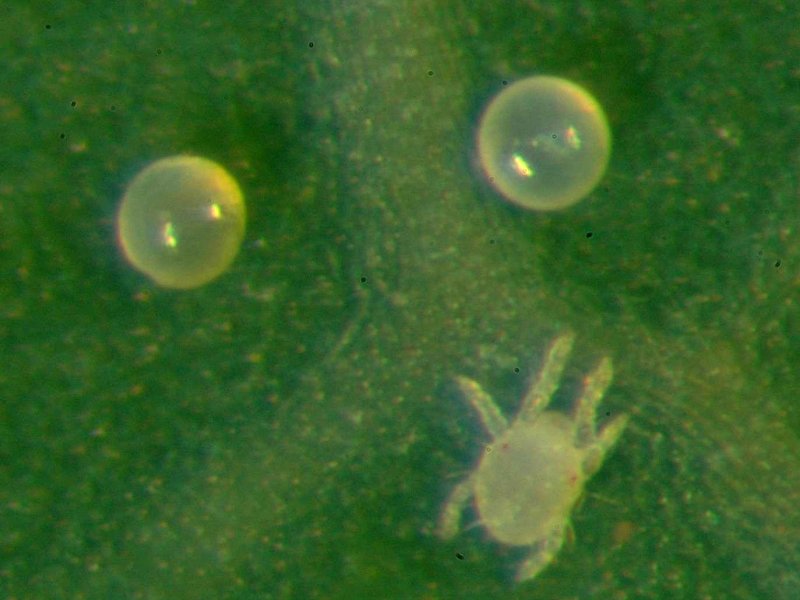

Cassava green spider mite (Mononychellus tanajoa or M. progresivus) This mite is green in colour at a young age turning yellowish as adult. Adult females attain a size of 0.8 mm. They appear as yellowish green specks to the naked eye. They occur on the lower surface of young leaves, green stems and auxiliary buds of cassava. Damage initially appears as yellowish "pinpricks" on the surface of young leaves.

Symptoms vary from a few chlorotic spots to complete chlorosis. These symptoms are somehow similar to African cassava mosaic disease, and should not be confused. Heavily attacked leaves are stunted and become deformed. Severe attacks cause the terminal leaves to die and drop, and the shoot tip looks like a "candle stick". Green spider mites are major pests in dry season. Severe mite attack results in 20-80 % loss in tuber yield.

Predatory mites (mainly Typhlodromalus aripo and T. manihoti) introduced from South America, the home of the cassava green mite, have given effective control of the cassava green mites in Africa (Yaninek and Hanna, 2003).

|

|

|

What to do:

|

|

Cassava scales (Aonidomytilus albus) It is a mussel-shaped scale with an elongated silvery-white cover and about 2-2.5 mm long. This scale may cover the stem with conspicuous white secretions, and eventually the leaves. This scale sucks from the stem and dehydrates it. The leaves of attacked plants turn pale, wilt and drop off. Severely attacked plants are stunted and yield poorly. Scale attack can kill cassava plants, in particular plants weakened by previous insect attack and drought. Stem cuttings derived from infested stem portions normally do not sprout. |

|

|

What to do:

|

|

Grasshoppers (Zonocerus variegatus) Grasshoppers such as the variegated grasshopper (West to East Africa south of the Sahara), and the elegant grasshopper (Z. elegans) (Southern Africa and East Africa) are brightly coloured grasshoppers.

Adults are dark green with yellow, black and orange marking on their bodies. Nymphs are black with yellow markings on the body, legs and antenna and wing pads. Female grasshoppers lay many eggs just below the surface of the soil in the shade under evergreen plants, usually outside cassava fields. Eggs are laid in masses of froth, which harden to form sponge-like packets, known as egg pods, which look like tiny groundnut pods. Eggs start to hatch at the beginning of the main dry season.

Grasshoppers attack a wide range of crops mainly in the seedling stage. They feed on cassava plants, chewing leaves and stems and may cause defoliation and debark stems. This is particularly severe in fields next to the bush when the dry season is prolonged. |

|

|

What to do:

|

|

Larger grain borer (Prostephanus truncatus) The larger grain borer has been found infesting cassava chips in storage particularly during the rainy season in West Africa. This beetle is currently the most serious pest of dried cassava in storage. Weight losses as high as 70% after 4 months of storage have been reported elsewhere. |

|

|

What to do:

For more information on Neem click here. |

|

Cassava mealybug (Phenacoccus manihoti) The cassava mealybug is pinkish in colour. Its body is surrounded by very short filaments, and covered with a fine coating of wax. Adults are 0.5-1.4 mm long. This mealybug does not have males. Females live for about 20 days and lay 400 eggs in average. The lifecycle from egg to adult is completed in about 1 month at 27°C. It reproduces throughout the year and it reaches peak densities during the dry season. Mealybugs are dispersed by wind and through planting material.

The cassava mealybug strongly prefers cassava and other Manihot species; other host crops and wild hosts are only marginally infested. It sucks sap at cassava shoot tips, on the lower surface of leaves, and on stems. During feeding the mealybug injects a toxin into the cassava plant causing deformation of terminal shoots, which become stunted, resulting in compression of terminal leaves into "bunchy tops". The length of internodes is reduced, and stems are distorted. When attack is severe plants die, starting at the plant tip, where most mealybugs are found.

Mealybug attack results in leaf loss and poor quality planting material (stem cuttings) due to dieback and weakening of stems used for crop propagation. Tuber losses have been estimated up to 80%. The pest-induced defoliation reduces availability of healthy leaves, which are consumed as leafy vegetables in most of West and Central Africa. After the pest cripples plant growth, weed and erosion sometimes lead to total destruction of the crops. In general, yield losses depend upon age of plant when attacked, length of dry season, severity of attack and general conditions of the plant. Mealybug damage is more severe in the dry than in the wet season.

The cassava mealybug was accidentally introduced to Africa from South America. After the first reports in the 1970s, the insect became the major cassava pest within a few years and spread rapidly through most of the African cassava belt. The outbreak led to famine in several countries where cassava is a staple crop and particularly important in times of drought. In an attempt to control this pest natural enemies, mainly parasitic wasps and ladybird beetles, were introduced from South America.

The most effective has been the parasitic wasp (Apoanagyrus (=Epidinocarsis) lopezi), which has kept this mealybug at low levels, resulting on significant reduction of yield losses in most areas in Africa (Neuenschwander, 2003). |

|

|

What to do:

|

|

Post harvest diseases Some fungi growth on cassava chips, usually when the moisture content of cassava chips exceeds 14%, making them unfit for feed and food. A survey of cassava chips processing areas of West Africa has indicated that the most common fungi were Rhizopus sp. and Aspergillus sp. (IITA, 1996).

|

|

|

What to do:

For more information on Storage pests click here. |

|

Red spider mites (Oligonychus gossypii and Tetranychus spp.) Several species of red spider mites also occur on cassava, mostly on the older leaves. Adults are about 0.6 mm long. Initial symptoms are yellowish pinpricks along the main vein of mature leaves. Spider mites produce protective webbing that can be readily seen on the plant. Attacked leaves turn reddish, brown or rusty in colour. Under severe mite attack, leaves die and drop beginning with older leaves. Most damage occurs at the beginning of the dry season. |

|

|

What to do:

|

|

Storage pests A number of beetles feed on dry cassava causing post harvest losses. In Benin Republic the most common are Dinoderus sp., Carpophilus sp., the coffee bean weevil (Araecerus fasciculatus), the lesser grain borer (Rhizopertha dominica), and more recently, the larger grain borer (Prostephanus truncatus).

Infestation by these insects is heavier in the rainy season than in the dry season, is more prevalent in the humid zone than in the savannah, and is found more in large chips than in smaller ones. Maximum infestation was found after 6 to 8 months in storage, at which time chips would fall into dust when squeezed (Bokanga, IITA, FAO).

|

|

|

What to do:

For more information on Neem click here. |

|

Striped mealybug (Ferrisia virgata) It is a whitish mealybug with two longitudinal dark stripes, long glassy wax threads and two long tails. It attains a length of 4 mm. The stripped mealybug occurs on the underside of leaves near the petioles and on the stems. It sucks sap but does not inject any toxin into plants. Severely attacked plants show general symptoms of weakening but do not show distortion. It is a minor pest of cassava, and no control is usually required as is controlled naturally by natural enemies. |

|

|

What to do:

|

|

Termites Different species of termites damage cassava stems and roots. Termites damage cassava planted late or in the dry season, in particular when the crop is still young at the peak of the dry season. They chew and eat stem cuttings which grow poorly, die and rot. The may destroy whole plantations. In older cassava plants termites chew and enter the stems. This weakens the stems and causes them to break easily. |

|

|

What to do:

|

|

Whiteflies (Bemisia tabaci, Aleurodicus dispersus) Several species of whiteflies are found on cassava in Africa. Feeding causes direct damage, which may cause considerable reduction in root yield if prolonged feeding occurs. Some whiteflies cause major damage to cassava as vectors of cassava viruses. The spiralling whitefly (Aleurodicus dispersus) was reported as a new pest of cassava in West Africa in the early 90s. The adults and nymphs of this whitefly occur in large numbers on the lower surfaces of leaves covered with large amount of white waxy material. Females lay eggs on the lower leaf surface in spiral patterns (like fingerprints) of white material secreted by the female. This whitefly sucks sap from cassava leaves. It excretes large amounts of honeydew, which supports the growth of black sooty mould on the plant, causing premature fall of older leaves.

The tobacco whitefly (Bemisia tabaci) transmits the African cassava mosaic virus, one of the most important factors limiting production in Africa. The adults and nymphs of the tobacco whitefly occur on the lower surface of young leaves. They are not covered with white material. The nymphs appear as pale yellow oval specks to the naked eye. |

|

|

What to do:

|

Geographical Distribution in Africa

Geographical Distribution of Cassava in Africa. Updated on 8th July 2019. Source FAOSTAT.

© OpenStreetMap contributors. © OpenMapTiles, GBIF.

Cassava is native of Latin America and was introduced to the African continent by Portuguese traders in the late 16th century. It is native to tropical South America but has been introduced into most countries in the tropics.

Read more

Local names (detailed):

Angola: Tombo (Umbundu), Mandioqueira (Portuguese), Mbowe (Umbundu) (Bossard, 1996)

Benin: Finyin, Golotin, Hunla, Sohwe (Fon, Mahi), Gbatchi, Baountchi (Ifè), Kpaki (Tchabè, Holly), Ajangun (Idatcha, Mahi, Ifè), Éguèkè (Mahi), Tamguma, Logo (Bariba), Loogo (Dendi), Otangoumbo (Gourmantché) (Achigan et al., 2010); Ege (Fatumbi, 1995); Fenyen (Fon), Fenyen (Goum), Paki, Gbaguda (Yoruba), (Nago), Logo (Ba), Loogo (Dendi), Loogoh (Peuhl) (Houndje et al., 2016)

Burkina Faso: Manioc, Tchapladakow (Dagara) (Maundu., 2015)

Burundi: Imyumbati (Kirundi) (Baerts & Lehmann, 1991)

Cameroon: Kwem (Chagomoka et al., 2014); Mbahi (Fulfuldé), Manioc (French) (Malzy, 1954); Mbom (Sangmelima, Yaoundé), Nkwamba (Douala), Kasinga (Bangangte) (Noumi & Tchakonang, 2001)

Central African Republic: Gueda (Gbaya Dialecte Bossangoa) (Boulesteix et al., 1979); Dowo, Ngale (Banda), Gadanga (Manja), Do (Dakpwa) (Vergiat, 1969)

Côte d'Ivoire: Gbou Kwé (Shien), Bédé (Ashanti) (Bouquet, 1974); Manioc (Vrai) (Koulibaly et al., 2016); Agba (Baoule) (Saraka et al., 2018)

DRC: Dioko, Saka-Saka (Kongo) (Latham and Mbuta., 2006); Mhogo (Swahili), Umuumbati (Kinyarwanda), Omuhoko (Hunde), Mumbarhi (Mashi), Muchanga (Nyanga) (Nord-Kivu, Goma) (Ayobangira et al., 2000); Ntomba (Brazzaville) (Kimpouni et al., 2018); Manioko (Kikongo) (Makumbelo et al., 2008); Umvumbati (Rusizi, Kivu) (Byavu et al., 2000)

Ethiopia: Mayokiya (Gumuz), Mayoki (Oromo) (Maundu, 2015).

Gabon: Mayaka (Bahoumbou), N'wondo (Bakota), Mboe (Fang), Oguma (Mpongwgwé), Iloti (Myéné) (Adjanohoun et al., 1984); Tsaghe (Bourobo et al., 1996); Moguma (Apindji), Iloti (Galoa, Nkomi, Orungu), Mboe (Fang), Pita (Banzabi), Gigongu (Eshira, Bavarama), Gigongo (Bavili), Gégongo (Mitsogo, Bavové, Ivéa), Gékwo (Mindumu), Yaka (Loango), Diyaga (Ngowé, Bavungu, Balumbu), Didjaga (Bapunu), Uvondo (Benga), Ovondo (Baléngi), Muyondo (Baduma), N'wondo (Bakèlè, Béséki, Bakota) (Walker & Sillans, 1961); (Mo-)Bata, (Eviya Language)

Ghana: Bankye (Asante-Twi) (Agyare et al., 2009)

Guinea: Manankou, Banankou (Malinké), Bantara (Poular), Yoka (Soussou), Manioc (French) (Carrière, 1994)

Guinea-Bissau: N’mandiok (Nalu) (Moreira, 2016)

Kenya: Kyanga (Kamba) (Kisangau; Kumwoko (Wanzala et al., 2012)

Loogo (Dendi), Otangoumbo (Gourmantché) (Achigan et al., 2010); Ege (Fatumbi, 1995); Fenyen (Fon), Fenyen (Goum), Paki, Gbaguda (Yoruba), (Nago), Logo (Ba), Loogo (Dendi), Loogoh (Peuhl) (Houndje et al., 2016)

Madagascar: Mahôgo (Tubercule), Ravimahôgo (Feuilles & Antakarana), Ambazaha, Belafanapaka, Belahazo, Kazaha, Mahago, Mangahoazo, Matreoka, Vihazo, Mbazaha, Rompotra, Vomangahazo (Malgache), Manioc (French), Cassava (English), Manioc, Mogo (Nicolas, 2012); Mahôgo (Tubercles), Ravimahôgo (Leaves) (Rivière et al., 2005)

Malawi: Ntapasya (Yao), Chigwanda (Yao), (Maundu, 2007)

Mauritius: Manioc (Creole), Maravali Karangon (Tamoul) (Daruty, 1911)

Mayotte: Muhogo (Shimaore & Kibushi) (Mchangama & Salaün, 2012)

Mozambique: Mtchocobwe (Ntxocobue), Matapa (Ndau) (Maundu, 2007)

Niger: Rogo (Hausa), Rogo (Zarma) (Saadou, 1993)

Nigeria: Gogoro (Ainslie, 1937); Iwa (Ibibio) (Ekpo et al., 2008); Gbaguda (Abo et al., 2008); Ege /Gbaguda (Yoruba), Abacha/Akpu (Igbo), Doya Danzaria (Hausa) (Aiyeloja & OA, B., 2006); Imidaka (Local Dialect); Icassava (Urhobo) (Iyamah & Idu, 2015).

Rwanda: Imyumbati (Kinyarwanda).

Senegal: Ekis (Diola) (Thomas, 1972)

Sierra Leone: Targa (Barnish & Samai, 1992); Tangae (Kpaa Mende) (Lebbie & Guries, 1995); Katakone (Ko) (Macfoy, 2013)

South Africa: Mutumbula (Vhavenda) (Constant & Tshisikhawe, 2018)

Sudan: Bavra (El-Kamali, 2009)

Tanzania: Mhogo (Amri & Kisangau, 2012); Kisamvu (Salinitro et al., 2017)

Togo: Agbéli, Akutéti, Katawoli (Ewé), Kuta (Mina) (Adjanohoun et al., 1986)

Uganda: Muhogo (Rutooro) (Namukobe et al., 2011)

General Information and Agronomic Aspects

Introduction

Cassava (Manihot esculenta) is a plant species belonging to the family Euphorbiaceae and the genus Manihot. The genus Manihot comprises about 100 recognized species, with Manihot esculenta being the most economically important and extensively cultivated species. Cassava typically grows as a shrub. Cassava is native of Latin America and was introduced to the African continent by Portuguese traders in the late 16th century.

Ⓒ Maundu, 2006

Cassava is native to South America but is now widely distributed throughout the tropics due to its adaptability to diverse environmental conditions. This hardy plant can thrive in poor soils and withstand drought, making it an important staple food crop for many regions with challenging agricultural conditions. Other factors that make cassava popular with small-scale farmers, particularly in Africa, are that it requires little labor in its production and there are no labor peaks because the necessary operations in its production can be spread throughout the year, and its yields fluctuate less than those of cereals.

The storage root (some people refer to it as "tuber") is a major source of energy and the leaves, which contain a high level of vitamin A and up to 17% protein, are often used as green vegetables. Its limitations are its poor nutritive value (mainly carbohydrates) and its cyanogenic glucoside content (HCN) that can lead to poisoning unless precautions (proper peeling/soaking in water/fermenting/drying/cooking) are taken during preparation of the tubers. Bitter cassava varieties tend to have a higher content of HCN.

Ⓒ Maundu, 2019

The main diseases affecting cassava are African cassava mosaic virus (ACMV), cassava bacterial blight, cassava anthracnose, and root rot. Pests and diseases, in combination with poor agronomic practices cause high yield losses in Africa. While biological and chemical control practices are available for other pests and diseases attacking cassava, ACMV is difficult to control. In severe cases, plants become stunted. In fact, this disease can cause up to 60% yield loss, and no biological or chemical control is now available to farmers. Given the vegetative propagation method used for cassava, availability of clean planting material for propagation is a major constraint, since white flies and infested planting material transmit the disease.

While cassava production demands few external inputs, labor and planting material are main costs of production. As a root crop, cassava requires a lot of labor to harvest. The production of cassava is dependent on a supply of good quality stem cuttings. The multiplication rate of these vegetative planting materials is very low, compared to grain crops, which are propagated by true seeds. Post-harvest deterioration of cassava is a major constraint. Cassava stem cuttings are bulky and highly perishable, drying up within a few days. Consequently, roots must be processed into a storable form soon after harvest. Farmers recognize post-harvest loss as a major risk factor in cassava production. Nevertheless, the rapid post-harvest perishability might lead to comparative disadvantages for small-scale producers linked to small-scale processing units. Furthermore, many cassava varieties contain cyanogenic glucosides, and inadequate processing can lead to high toxicity. Various processing methods, such as grating, sun drying, and fermenting, are used to reduce the cyanide content.

(Allem, 2001, De Oliveira & Miglioranza, 2014, Heuzé, 2016).

Cassava is grown on an estimated 80 million hectares in 34 African countries. It is an important crop in subsistence farming, as it requires few production skills or inputs. It is drought tolerant and produces reasonable yields under adverse conditions. Most important is its ability to remain in the soil as a famine reserve. Other factors that make cassava popular with small-scale farmers, particularly in Africa, are that it requires little labour in its production and there are no labour peaks because the necessary operations in its production can be spread throughout the year, and its yields fluctuate less than those of cereals.

|

| Cassava KME 2, 6 months old |

|

© A.A.Seif, icipe |

The storage root (some people refer to it as "tuber") is a major source of energy and the leaves, which contain a high level of vitamin A and up to 17% protein, are often used as green vegetables. Its limitations are its poor nutritive value (mainly carbohydrates) and its cyanogenic glucoside content (HCN) that can lead to poisoning unless precautions (proper peeling/soaking in water/fermenting/drying/cooking) are taken during preparation of the tubers. The latter is only applicable to bitter cassava varieties. Sweet varieties can even be eaten raw and fresh as they have very low content of HCN.

The main diseases affecting cassava are African cassava mosaic virus (ACMV), cassava bacterial blight, cassava anthracnose, and root rot. Pests and diseases, in combination with poor agronomic practices cause high yield losses in Africa. While biological and chemical control practices are available for other pests and diseases attacking cassava, ACMV is difficult to control. In severe cases, plants become stunted. In fact, this disease can cause up to 60% yield loss, and no biological or chemical control is now available to farmers. Given the vegetative propagation method used for cassava, availability of clean planting material for propagation is a major constraint, since white flies and infested planting material transmit the disease.

While cassava production demands few external inputs, labour and planting material are main costs of production. As a root crop, cassava requires a lot of labour to harvest. The production of cassava is dependent on a supply of good quality stem cuttings. The multiplication rate of these vegetative planting materials is very low, compared to grain crops, which are propagated by true seeds. Post harvest deterioration of cassava is a major constraint. Cassava stem cuttings are bulky and highly perishable, drying up within a few days. Consequently, roots must be processed into a storable form soon after harvest. Farmers recognise post harvest loss as a major risk factor in cassava production. Nevertheless, the rapid post harvest perishability might lead to comparative disadvantages for small-scale producers linked to small-scale processing units.

Furthermore, many cassava varieties contain cyanogenic glucosides, and inadequate processing can lead to high toxicity. Various processing methods, such as grating, sun drying, and fermenting, are used to reduce the cyanide content.

Species account

Cassava, is a perennial woody shrub that grows to a height of 1 to 3 meters. The plant has an upright, branching stem covered with rough, brown bark. Leaves: large, palmate leaves with five to seven lobes. The leaves grow only at the end of the branches and are dark green above and light green below. Flowers: unisexual, small and inconspicuous, five-petaled, green or crimson-red, depending on the variety. The male flowers are clustered in panicles, while the female flowers are solitary or few in number. Roots: cylindrical, conical, or irregularly shaped with a tapered point, 20- 60 cm long sometimes longer, vary in shape, and color (white and cream to yellow and purple) depending on the cultivar and environmental conditions. The flesh of the tuber is typically white or pale yellow pulp wrapped in thick brown skin.

Ⓒ Maundu, 2006

Ⓒ Adeka et al., 2005.

©A.A.Seif

©A.A.Seif

©A.A.Seif

Furthermore, there is considerable variation in the levels of cyanogenic compounds found in different cassava cultivars. Cyanogenic compounds are natural toxins that, when consumed in excessive amounts, can cause health issues. However, selective breeding and modern agricultural practices have led to the development of low-cyanide or cyanide-free cultivars, which are safe for consumption after proper processing (Heuzé, 2016, De Oliveira & Miglioranza, 2014).

When selecting ideal cassava cultivar, farmers consider adaptability to local conditions, yield potential, agronomic characteristics, and culinary qualities. Consulting with local extension providers is crucial for region-specific recommendations.

Varieties

A number of both local and newer varieties exist in Kenya:

Cassava varieties in coastal and eastern Kenya (Source: KALRO/KEPHIS)

|

Variety |

Optimal production altitude range (masl) (region) |

Maturity (months) |

Tuber yield (t/ha) |

Special attributes |

|

"5543/156" |

1-500 (coast/eastern lowlands) |

10-12 |

40-50 |

Tolerant to ACMD; bitter, high yielding variety for livestock. |

|

"Guso" |

1-700 (coast/eastern lowlands) |

12-15 |

20-40 |

Resistant to (ACMD); Better yielder than Kaleso. Also for human consumption, sweet |

|

"Kaleso" ("46106/27") |

1-1500 (coast /eastern) |

10-12 |

25-30 |

Tolerant to ACMD and cassava brown streak disease (CBSD); sweet, high yielding, for human consumption. |

|

"Karembo" ("KME-08-05") |

15-1200 (coast/eastern) |

8 |

50-70 |

Tolerant to ACMD and CBSD; sweet; short with open structure, |

|

"Karibuni" ("KME-08-01") |

15-1200 (coast/eastern) |

8-12 |

50-70 |

Tolerant to ACMD and CBSD; sweet; high branching; good for intercropping |

|

"Kibanda Meno" |

1-500 (coast/eastern) |

6-8 |

20-30 |

Local type. Popular at Kenya’s coast. Very susceptible to ACM; very sweet |

|

"Katsunga" |

1-500 (coastal lowlands) |

|

|

Local coastal variety. leaves cooked |

|

"KME 1" |

250-1500 (eastern) |

12-14 |

20 |

Sweet |

|

"KME 2" |

250-1500 (eastern) |

8-10 |

40 |

Tolerant to ACMD; sweet, less fibrous and has low cyanide content |

|

"KME 3" |

250-1500 (eastern) |

8-10 |

40 |

Tolerant to ACMD; sweet |

|

"KME 4" |

250-1500 (eastern) |

8-10 |

40 |

Tolerant to ACMD; sweet |

|

"KME 61" |

250-1500 (eastern) |

14 |

35 |

Tolerant to ACMD; bitter and more fibrous than KME 2 |

|

"Mucericeri" |

250-1750 (eastern) |

12-14 |

20 |

Sweet |

|

"Nzalauka" ("KME-08-06") |

15-1200 (coast/eastern) |

6-8 |

50-70 |

Tolerant to ACMD and CBSD; sweet; straight stems ideal for intercropping |

|

"Shibe" ("KME-08-04") |

15-1200 (coast/eastern) |

8-12 |

50-70 |

Tolerant to ACMD and CBSD; sweet; straight stems ideal for intercropping |

|

"Siri" |

15-1200 (coast/eastern) |

8-12 |

50 |

Tolerant to ACMD and CBSD; sweet; very short without branches |

|

"Tajirika" ("KME-08-02") |

15-1200 (coast/eastern) |

8 |

50-70 |

Tolerant to ACMD and CBSD; sweet; straight stems ideal for intercropping |

Western Kenya varieties

"2200", "Tereka", "Serere", "Adhiambo lera", "CKI", "TMS 60142", "BAO", "Migyeera", "SS 4", "MH 95/0183", "MM 96/2480", "MM 96/4884", "MM 96/5280", "MM 96/5588", "MM 97/2270".

Examples of cassava varieties grown in Tanzania (varieties listed are resistant/tolerant to ACMD)

• "Kachaga"

• "191/0057"

• "191/0063"

• "191/0067"

• "MM 96/0876"

• "MM 96/3075B"

• "MM 96/4619"

• "MM 96/4684"

• "MM 96/5725"

• "MM 96/8233"

• "MM 96/8450"

• "SS 4"

• "TME 14"

• "TMS 4(2)1425"

Examples of cassava varieties grown in Uganda (varieties listed are resistant/tolerant to ACMD)

• "Migyeera"

• "NASE 1 to 12"

• "SS 4"

• "TME 14"

• "TMS 4(2)1425"

• "TMS 192/0067"

• "TMS 50395"

"Uganda MH 97/2961"

Ecological information

In equatorial areas, cassava can be grown up to 1500 m altitude. The optimum temperature range is 20-30deg. Specific cultivars are necessary for successful cultivation at an average temperature of 20deg. Cassava is grown in regions with 500-6000 mm of rainfall per year. Optimum annual rainfall is 1000-1500 mm, without distinct dry periods. Once established, cassava can resist severe drought. With prolonged periods of drought, cassava plants shed their leaves but resume growth after the rains start, making it a suitable crop in areas with uncertain rainfall distribution. Because of its drought resistance, in many regions cassava is planted as a reserve crop against famine in dry years. Good drainage is essential for cassava; the crop does not tolerate water logging. High irradiance is preferred.

Best growth and yield are obtained on fertile sandy loams. Cassava is able to produce reasonable yields on severely depleted or even eroded soils where other crops fail. Gravelly or stony soils cause problems with root penetration and are unsuitable. Also heavy clay or other poorly drained soils are not suitable.

Cassava growth and yield are reduced drastically on saline soils and on alkaline soils with a pH above 8.0. The optimum pH is between 5.5 and 7.5, but cultivars are available that tolerate a pH as low as 4.6 or as high as 8.0. Reasonably salt-tolerant cultivars have also been selected. Very fertile soils encourage excessive foliage growth at the expense of storage roots.

Agronomic aspects

Propagation from storage roots is impossible, as the roots have no buds. Cassava is propagated through cuttings. The most suitable cuttings are 20-30 cm long and 20-25 mm in diameter (with 5-8 nodes), preferably from the middle browned-skinned portion of the stems of plants 8-14 months old. Cuttings from older, more mature parts of the stem give better yield than cuttings from younger parts, and long cuttings give higher yields than short cuttings. Select cuttings from healthy plants. Cuttings slightly infested with pests can be treated by immersion in heated water (mixing equal volumes of boiling and cold water) for 5-10 minutes just before planting.

The interval between cutting stems and planting should be as short as possible (not more than a couple of days). Cassava cuttings may be planted vertically, at an angle, or horizontally. The drier the soil the bigger the part of the stem placed in the soil. Under very dry conditions, plant cuttings at an angle and cover the larger part with soil. Vertical planting is best in sandy soils, as the roots develop deeper in the soil. Horizontal planting leads to a large number of thin stems, which may cause lodging. Moreover, the roots develop more closely to the surface and are more likely to be exposed and attacked by rodents and birds. Do not plant cuttings upside down, as this drastically reduces yield.

The spacing between plants will depend on whether cassava is grown as a sole crop or with other crops (intercropping). If cassava is being grown alone, plants should be planted 1 meter apart from each other. This means that 10.000 cuttings are required for 1 ha (4000 cuttings per acre). If cassava is being grown as an intercrop, the branching habit of both the cassava and the other crops should be considered, making sure there is enough space for the plants.

The best land for planting cassava is flat or gently sloping land. Steep slopes are easily eroded. Valleys and depression areas that usually get waterlogged are not very suitable and cassava roots do not develop well. Before planting get to know the history of the land (previous crops, types of weeds, diseases and pests).

Soil preparation varies from practically zero under shifting cultivation to ploughing, harrowing and possible ridging in more intensive cropping systems. Planting on mounds and ridges is recommended, especially for areas with rainfall of more than 1200 mm per year or in areas where soils get waterlogged (e.g. valleys and depressions). Ridging may not give higher yield, but harvesting is easier and soil erosion may be reduced, especially by contoured ridges. In sandy soils, minimum tillage and planting cassava on the flat are appropriate. Plant at the beginning of the rainy season.

Husbandry

Weeding is necessary every 3-4 weeks until 2-3 months after planting. Afterwards the canopy may cover the soil and weeding is less necessary. Although cassava grows rather well on poor soils, it requires large amount of nutrients to produce high yields. To maintain high yields, it is necessary to maintain the fertility of the soil. Phosphorous is important for root development. Symptoms of phosphorous deficiency are stunted growth and violet or purple discoloration of the leaves. In the absence of good compost, rock phosphate can be applied if needed. Potassium is also needed by cassava and can be applied in the form of compost or wood ashes. Potassium deficiency symptoms are: stunted growth, dark leaf color which gradually becomes paler, dry brown spots on tips and margins of the leaves and "burnt" edges of leaves.

Fertilizers and manures are usually not used by small-scale cassava growers in most African countries because, in many cases, they cannot afford such additional inputs. However, it is important to provide good growing conditions for the plants, as healthy plants are able to withstand some damage by pests and diseases. In general, cassava responds well to farmyard manure. Manure can be applied at land preparation to increase soil nutrients, to improve the soil structure, and to improve the ability of the soil to hold water. Mulching cassava, especially after planting, is helpful when growing cassava in dry areas or on slopes.

Crop rotation and intercropping

There is a wide variety of cropping patterns and rotations with cassava. Though rotation with other crops is preferable, cassava is sometimes grown continuously on the same land, especially in dry areas not suitable for other crops. When grown in bush-fallow systems, cassava is usually planted at the end of the rotation cycle, as it still produces relatively well at lower fertility levels and also allows a smooth transition to the fallow.

Cassava when planted as an intercrop along with cowpea groundnut or tree crops like Leucaena reduces soil run-off and soil-loss. Forage yield of Leucaena improves when grown with cassava and groundnut. Canavalia or Crotalaria (legume crops) when planted as intercrops with cassava improves soil productivity. Sow 1 row of Canavalia or Crotalaria between rows of cassava immediately after planting cassava. Let these grow until harvest. Plough after harvest to incorporate crop residues into the soil.

|

| Cassava KME 2, 6 months old |

|

© A.A.Seif, icipe |

|

| Cassava KME 2, 12 months |

|

© A.A.Seif, icipe |

|

| Cassava KME 2, 18 months old |

|

© A.A.Seif, icipe |

For more information on these varieties please contact the Kenya Agriculture and Livestock Research Organization (KALRO).

Harvest, post-harvest practices and markets

Harvesting

Harvesting is done either piece-meal or by uprooting whole plants. Young plants are usually harvested piece-meal, while old plants are more commonly uprooted to prevent the storage roots becoming very fibrous. As cassava roots do not keep fresh more than 2-3 days after harvesting, not all plants are harvested at once, but rather harvesting as the roots are consumed. When cassava is grown for urban markets they are harvested in bulk. Cassava is usually harvested 9-12 months after planting. It is sometimes harvested earlier if needed for food. Storage roots become too woody if harvesting is delayed. Early maturing varieties are ready for harvesting at 6 months while late maturing varieties are ready 12 months after planting.

Post-harvest practices

Cassava does not store well when fresh and therefore has to be peeled, chopped and dried in the sun. It can then be stored in the form of chips or flour under dry conditions.

Average yields are between 3-4 tons of fresh tubers per acre (7.5-10 tons per ha) although with reasonable care and attention yields of up to 10 tons per acre (25 tons per ha) and more are possible. The ratio of fresh tubers to peeled and dried chips is about 3:1.

Cassava processing techniques can be employed to reduce cyanide levels and ensure the safety of the final product. The initial cyanide level in cassava roots should not exceed 200 mg/kg, according to the Food and Agricultural Organization/World Health Organization. To reduce cyanide levels, soaking the tuber for three days followed by boiling in salt-vinegar water eliminates hydrogen cyanide (HCN). Studies show that cyanide levels decrease by about 30% after four days of cassava storage, 50% after boiling, 80% when grated and boiled, and 50% when grated and cooked in an earth oven.

Fermentation is another effective method. Yeast combined with lactic acid bacteria is more successful than using either organism alone. Traditional fermentation usually takes around six days. Grinding and drying the cassava also contribute to reducing cyanide levels. Grinding exposes the linamarase enzyme, which converts toxic compounds into volatile ones. Sun-drying the product reduces moisture content, but a combination of drying and grinding is most effective (farmlinkkenya.com).

Ⓒ Adeka et al., 2005

Value addition and markets

After detoxification, cassava root tubers can be dried and ground to cassava flour. The flour is a gluten-free baking alternative and can be combined with other flours, such as millet or wheat, to improve the nutritional profile of the product. Composite cassava flours are used in preparation of porridge, ugali, traditional cassava beer, thickening of sauces and production of various baked goods and pastries. Additional processing techniques include making cassava chips by boiling and deep-frying the peeled cassava, producing cassava crisps by slicing and frying thin pieces, and creating dried cassava leaves powder by boiling and drying the leaves. Cassava peels can also be used as animal feed or recycled as fertilizer (farmlinkkenya.com, webmd.com).

Ⓒ Adeka et al., 2005

Ⓒ Adeka et al., 2005

Approximately half of the world's cassava production occurs in Africa, where it is cultivated in about 40 African countries. Nigeria, the Democratic Republic of Congo, and Tanzania account for around 70% of Africa's cassava output. Nigeria, Thailand, Indonesia, Brazil, Congo, and Ghana are major global cassava producers. Nigeria remains the largest consumer due to its large population, while China, Indonesia, Thailand, and sub-Saharan African countries also contribute to consumption. The demand for cassava products is growing in Europe, North America, and Asia, driven by the popularity of gluten-free and sustainable alternatives (Expert Market research, IITA, n.d).

Manual from IITA Starting a cassava farm. Of the world production of cassava, 65% is used directly for human consumption, 20% for animal feed and the remaining 15% for starch and industrial uses (alcohol production). In Africa, stems are often used as firewood.

Nutritional value and recipes

Cassava is a starch-tuber that can be eaten as a whole root or root chips, or grated to make flour used for baking. It is highly valued for its nutritional content and numerous health benefits. Cassava is particularly rich in carbohydrates providing a significant energy boost. The carbohydrates in cassava are mainly in the form of starch, which is gradually released into the bloodstream, providing sustained energy levels and promoting satiety. Cassava is also rich in dietary fiber, which aids in proper digestion and helps prevent constipation. Fiber is known to promote a healthy digestive system, regulate bowel movements, and contribute to weight management. Incorporating cassava into your diet can provide a natural and healthy way to increase your fiber intake.

Cassava also contains minerals such as calcium, magnesium, potassium, and iron. Calcium is crucial for strong bones and teeth, while magnesium helps regulate blood pressure and supports muscle function. Potassium is essential for maintaining proper heart function and fluid balance, and iron is necessary for the production of red blood cells, preventing anemia. Furthermore, cassava contains essential vitamins and minerals that are beneficial for overall health. It is a good source of vitamin C, an antioxidant that boosts the immune system and helps protect the body against common illnesses. Vitamin C also plays a vital role in collagen synthesis, promoting healthy skin and wound healing.

In addition to vitamin C, cassava is rich in vitamin B-complex, including thiamine (B1), riboflavin (B2), niacin (B3), and pyridoxine (B6). These vitamins are essential for converting food into energy, supporting brain function, maintaining a healthy nervous system, and promoting proper growth and development.

Cassava flour, derived from cassava roots, has gained popularity as a gluten-free alternative to wheat flour. This makes it a suitable option for individuals with gluten sensitivities or celiac disease. Cassava flour is also a good source of resistant starch, a type of carbohydrate that resists digestion and acts as a prebiotic, promoting the growth of beneficial gut bacteria.

One notable aspect of cassava is its low fat and cholesterol content. This makes it a suitable food choice for individuals looking to maintain a healthy weight or reduce their cholesterol levels.

However, it's important to note that cassava contains naturally occurring compounds called cyanogenic glycosides, which can be toxic if consumed in excessive amounts. Therefore, it is essential to properly process cassava before consumption to remove these toxins, such as peeling, soaking, fermenting, or cooking it thoroughly (Healthline, n.d, Webmd.com, farmlinkkenya.com).

Table 1: Proximate nutritional value of 100 g of cassava

Food name |

Cassava, root, white, peeled, raw |

Cassava, root, white, peeled, boiled, drained (without salt) |

Cassava Flour Ugali |

Cassava Porridge (Uji wa Muhogo) |

Recommended daily allowance (approx.) for adults a |

Edible conversion factor |

0.93 |

1 |

|||

Energy (kJ) |

733 |

627 |

788 |

121 |

9623 |

Energy (kcal) |

173 |

148 |

186 |

28 |

2300 |

Water (g) |

53.8 |

60.5 |

51.6 |

92.6 |

2000-3000c |

Protein (g) |

1.3 |

1.1 |

1.1 |

0.1 |

50 |

Fat (g) |

0.3 |

0.2 |

0.3 |

0 |

<30 (male), <20 (female)b |

Carbohydrates (g) |

39.1 |

33.4 |

43.7 |

6.8 |

225 -325g |

Fiber (g) |

4.6 |

3.9 |

2.2 |

0.3 |

30d |

Ash (g) |

1 |

0.8 |

1.3 |

0.2 |

|

Mineral composition |

|||||

Ca (mg) |

33 |

27 |

79 |

12 |

800 |

Fe (mg) |

0.9 |

0.7 |

0.8 |

0.1 |

14 |

Mg (mg) |

13 |

10 |

26 |

4 |

300 |

P (mg) |

21 |

17 |

57 |

7 |

800 |

K (mg) |

250 |

171 |

326 |

39 |

4700f |

Na (mg) |

2 |

1 |

20 |

5 |

<2300e |

Zn (mg) |

0.34 |

0.26 |

0.41 |

0.05 |

15 |

Se (mg) |

1 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

30 |

Bioactive compound composition |

|||||

VIT A RAE (mcg) |

1 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

800 |

VIT A RE (mcg) |

1 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

800 |

Retinol (mcg) |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1000 |

Beta carotene (mcg) |

8 |

6 |

7 |

1 |

600 – 1500g |

Thiamin (mg) |

0.23 |

0.15 |

0.03 |

0 |

1.4 |

Riboflavin (mg) |

0.01 |

0.01 |

0.05 |

0.01 |

1.6 |

Niacin (mg) |

0.4 |

0.3 |

0.6 |

0.1 |

18 |

Dietary folate (mcg) |

27 |

15 |

18 |

2 |

400f |

VIT B12 (mcg) |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

3 |

VIT C (mg) |

38 |

23 |

1.8 |

0.2 |

60 |

Source (Nutrient data): FAO/Government of Kenya. 2018. Kenya Food Composition Tables. Nairobi, 254 pp. http://www.fao.org/3/I9120EN/i9120en.pdf

a Lewis, J. 2019. Codex nutrient reference values. Rome. FAO and WHO

b NHS (refers to saturated fat)

c https://www.hsph.harvard.edu/nutritionsource/water/

d British Heart Foundation

e FDA

f NIH

g Mayo Clinic

Recipes

1. Congolese manioc and maize flour fufu

(DRC recipe. Source: Maundu at al., 2007)

The Congolese cook fufu from maize flour and manioc flour.

Ingredients

• Cassava flour

• Maize flour

• Water

Preparation:

• Heat water in cooking pot.

• Add maize flour before the water gets hot.

• Let it cook as you stir with a cooking stick for about 15 minutes till the mixture changes to brown.

• Add manioc flour, and stir while the pot is still on fire. Blend the mixture well, breaking up any lumps with the wooden spoon. Dip the wooden spoon in hot water then use it to mould the fufu into a round ball.

• Stir and turn with more force until the mixture hardens and changes its aroma.

• Remove from fire and serve with an accompaniment like vegetables or some stew.

Note: Cassava flour fufu has a gummy consistency. Cassava flour is best when mixed with other flours e.g. maize/corn or millet to mask the gummy consistency thus the fufu becomes more compact or cements well after cooking.

2. Atap

(Teso recipe. Source: Maundu at al., 2007)

In the preparation of ugali, 1 cup of water (250 ml) makes ugali serving one grown up. Water quantities can thus be adjusted to suit the number of individuals.

Ingredients

2 cups Water

250g Flour (Mixture: millet, sorghum & cassava flour. One part of each)

Preparation

Mix millet, sorghum and cassava flour.

Boil water in a saucepan.

Add the flour little by little, stirring continuously until the mixture stiffens desirably.

Simmer and cook for 45 minutes.

This kind of ugali is high in energy and micronutrients.

It is also very nutritious for children. Good for dry areas where maize doesn’t do well.

3. Nni-oka

(West African recipe)

Ingredients

• 1 cup cassava flour

• 1 cup fermented corn flour

• 4 cups water for cooking

Method

• Boil water in a pot

• Set the corn flour in a bowl, add approximately 1 cup of cold water, mix well into a medium thick smooth paste

• When water boils, reduce the heat and set aside half the boiling water (to be used later)

• Stir in the corn paste into the pot of boiling water. With a wooden spoon stir continuously until the paste gelatinizes and thickens slightly

• Add cassava flour a little at a time stirring vigorously to avoid lumps from forming

• Blend the mixture (nni-oka) very well, breaking up any lumps with the wooden spoon

• Add about half of the water set aside and cover the pot. Leave it to cook for about 10-15 minutes

• Blend well into stiff but soft dough adding more water if nni-oka if it is still too stiff

• Turn nni-oka into a serving dish and serve hot with okro (okra) or agbono soup

Remarks

• This preparation has no gummy consistency

• You can also use a mixture of flours, e.g. finger millet, pearl millet, sorghum and cassava

• For mixed flours, use 4 cups of mixed flour and 5 cups of water.

• Enough for 4 people

4. Akpu

(West African recipe)

Ingredients

• Wet cassava paste (desired amount)

• Water for cooking

Method

• Set a pot half filled with water to boil

• In a convenient round bowl or a mortar, kneed the cassava paste to obtain a uniform slightly pliable consistency

• Mould into round shaped convenient sized balls and carefully place them in the pot of boiling water (the moulded cassava balls should be covered by the boiling water)

• Cover pot and cook under moderate heat for 20-25 minutes (depending on the quantity of cassava paste)

• When cooked, (cassava balls should look amylaceous or starchy) lift the cassava balls from the water into a mortar and pound with a pestle until the resulting dough (fufu) is satiny smooth and soft in texture, adding intermittently small quantities of hot water to further soften the fufu if necessary

• Mound the fufu into a serving dish and serve hot with any vegetable soup (preferably bitter leaf soup)

Note: Fermented wet cassava paste can be purchased from local markets.

Information on Pests

Furthermore, many cassava varieties contain cyanogenic glucosides, and inadequate processing can lead to high toxicity. Various processing methods, such as grating, sun drying, and fermenting, are used to reduce the cyanide content.

| Cassava mealybug (Phenacoccus manihoti) The cassava mealybug is pinkish in colour. Its body is surrounded by very short filaments, and covered with a fine coating of wax. Adults are 0.5-1.4 mm long. This mealybug does not have males. Females live for about 20 days and lay 400 eggs in average. The lifecycle from egg to adult is completed in about 1 month at 27°C. It reproduces throughout the year and it reaches peak densities during the dry season. Mealybugs are dispersed by wind and through planting material.

The cassava mealybug strongly prefers cassava and other Manihot species; other host crops and wild hosts are only marginally infested. It sucks sap at cassava shoot tips, on the lower surface of leaves, and on stems. During feeding the mealybug injects a toxin into the cassava plant causing deformation of terminal shoots, which become stunted, resulting in compression of terminal leaves into "bunchy tops". The length of internodes is reduced, and stems are distorted. When attack is severe plants die, starting at the plant tip, where most mealybugs are found.

Mealybug attack results in leaf loss and poor quality planting material (stem cuttings) due to dieback and weakening of stems used for crop propagation. Tuber losses have been estimated up to 80%. The pest-induced defoliation reduces availability of healthy leaves, which are consumed as leafy vegetables in most of West and Central Africa. After the pest cripples plant growth, weed and erosion sometimes lead to total destruction of the crops. In general, yield losses depend upon age of plant when attacked, length of dry season, severity of attack and general conditions of the plant. Mealybug damage is more severe in the dry than in the wet season.

The cassava mealybug was accidentally introduced to Africa from South America. After the first reports in the 1970s, the insect became the major cassava pest within a few years and spread rapidly through most of the African cassava belt. The outbreak led to famine in several countries where cassava is a staple crop and particularly important in times of drought. In an attempt to control this pest natural enemies, mainly parasitic wasps and ladybird beetles, were introduced from South America.

The most effective has been the parasitic wasp (Apoanagyrus (=Epidinocarsis) lopezi), which has kept this mealybug at low levels, resulting on significant reduction of yield losses in most areas in Africa (Neuenschwander, 2003). What to do:

|

| Larger grain borer (Prostephanus truncatus) The larger grain borer has been found infesting cassava chips in storage particularly during the rainy season in West Africa. This beetle is currently the most serious pest of dried cassava in storage. Weight losses as high as 70% after 4 months of storage have been reported elsewhere. What to do:

For more information on Neem click here. |

| Birds and other vertebrate pests Birds, rodents, monkeys, pigs and domestic animals (cattle, goat and sheep) are common vertebrate pests of cassava.

Measures that help to manage damage by these pests include: What to do:

|

| Striped mealybug (Ferrisia virgata) It is a whitish mealybug with two longitudinal dark stripes, long glassy wax threads and two long tails. It attains a length of 4 mm. The stripped mealybug occurs on the underside of leaves near the petioles and on the stems. It sucks sap but does not inject any toxin into plants. Severely attacked plants show general symptoms of weakening but do not show distortion. It is a minor pest of cassava, and no control is usually required as is controlled naturally by natural enemies. What to do:

|

| Cassava green spider mite (Mononychellus tanajoa or M. progresivus) This mite is green in colour at a young age turning yellowish as adult. Adult females attain a size of 0.8 mm. They appear as yellowish green specks to the naked eye. They occur on the lower surface of young leaves, green stems and auxiliary buds of cassava. Damage initially appears as yellowish "pinpricks" on the surface of young leaves.

Symptoms vary from a few chlorotic spots to complete chlorosis. These symptoms are somehow similar to African cassava mosaic disease, and should not be confused. Heavily attacked leaves are stunted and become deformed. Severe attacks cause the terminal leaves to die and drop, and the shoot tip looks like a "candle stick". Green spider mites are major pests in dry season. Severe mite attack results in 20-80 % loss in tuber yield.

Predatory mites (mainly Typhlodromalus aripo and T. manihoti) introduced from South America, the home of the cassava green mite, have given effective control of the cassava green mites in Africa (Yaninek and Hanna, 2003).

What to do:

|

| Red spider mites (Oligonychus gossypii and Tetranychus spp.) Several species of red spider mites also occur on cassava, mostly on the older leaves. Adults are about 0.6 mm long. Initial symptoms are yellowish pinpricks along the main vein of mature leaves. Spider mites produce protective webbing that can be readily seen on the plant. Attacked leaves turn reddish, brown or rusty in colour. Under severe mite attack, leaves die and drop beginning with older leaves. Most damage occurs at the beginning of the dry season. What to do:

|

| Cassava scales (Aonidomytilus albus) It is a mussel-shaped scale with an elongated silvery-white cover and about 2-2.5 mm long. This scale may cover the stem with conspicuous white secretions, and eventually the leaves. This scale sucks from the stem and dehydrates it. The leaves of attacked plants turn pale, wilt and drop off. Severely attacked plants are stunted and yield poorly. Scale attack can kill cassava plants, in particular plants weakened by previous insect attack and drought. Stem cuttings derived from infested stem portions normally do not sprout. What to do:

|

| Grasshoppers (Zonocerus variegatus) Grasshoppers such as the variegated grasshopper (West to East Africa south of the Sahara), and the elegant grasshopper (Z. elegans) (Southern Africa and East Africa) are brightly coloured grasshoppers.

Adults are dark green with yellow, black and orange marking on their bodies. Nymphs are black with yellow markings on the body, legs and antenna and wing pads. Female grasshoppers lay many eggs just below the surface of the soil in the shade under evergreen plants, usually outside cassava fields. Eggs are laid in masses of froth, which harden to form sponge-like packets, known as egg pods, which look like tiny groundnut pods. Eggs start to hatch at the beginning of the main dry season.

Grasshoppers attack a wide range of crops mainly in the seedling stage. They feed on cassava plants, chewing leaves and stems and may cause defoliation and debark stems. This is particularly severe in fields next to the bush when the dry season is prolonged. What to do:

|

| Whiteflies (Bemisia tabaci, Aleurodicus dispersus) Several species of whiteflies are found on cassava in Africa. Feeding causes direct damage, which may cause considerable reduction in root yield if prolonged feeding occurs. Some whiteflies cause major damage to cassava as vectors of cassava viruses. The spiralling whitefly (Aleurodicus dispersus) was reported as a new pest of cassava in West Africa in the early 90s. The adults and nymphs of this whitefly occur in large numbers on the lower surfaces of leaves covered with large amount of white waxy material. Females lay eggs on the lower leaf surface in spiral patterns (like fingerprints) of white material secreted by the female. This whitefly sucks sap from cassava leaves. It excretes large amounts of honeydew, which supports the growth of black sooty mould on the plant, causing premature fall of older leaves.

The tobacco whitefly (Bemisia tabaci) transmits the African cassava mosaic virus, one of the most important factors limiting production in Africa. The adults and nymphs of the tobacco whitefly occur on the lower surface of young leaves. They are not covered with white material. The nymphs appear as pale yellow oval specks to the naked eye. What to do:

|

| Different species of termites damage cassava stems and roots. Termites damage cassava planted late or in the dry season, in particular when the crop is still young at the peak of the dry season. They chew and eat stem cuttings which grow poorly, die and rot. The may destroy whole plantations. In older cassava plants termites chew and enter the stems. This weakens the stems and causes them to break easily. What to do:

|

| A number of beetles feed on dry cassava causing post harvest losses. In Benin Republic the most common are Dinoderus sp., Carpophilus sp., the coffee bean weevil (Araecerus fasciculatus), the lesser grain borer (Rhizopertha dominica), and more recently, the larger grain borer (Prostephanus truncatus).

Infestation by these insects is heavier in the rainy season than in the dry season, is more prevalent in the humid zone than in the savannah, and is found more in large chips than in smaller ones. Maximum infestation was found after 6 to 8 months in storage, at which time chips would fall into dust when squeezed (Bokanga, IITA, FAO).

What to do:

For more information on Neem click here. |

| African Cassava Mosaic Disease (ACMD) African cassava mosaic disease is one of the most serious and widespread diseases throughout cassava growing areas in Africa, causing yield reductions of up to 90%. It is spread through infected cuttings and by whiteflies (Bemisia tabaci).

Symptoms occur as characteristic leaf mosaic patterns that affect discrete areas and are determined at an early stage of leaf development. Symptoms vary from leaf to leaf, shoot to shoot and plant to plant, even of the same variety and virus strain in the same locality. Some leaves situated between affected ones may seem normal and give the appearance of recovery. What to do:

|

| Cassava bacterial blight (Xanthomonas campestris pv. manihotis) It is a major constraint to cassava cultivation in Africa. Infected leaves show localised, angular, water-soaked areas. Under severe disease attack heavy defoliation occurs, leaving bare stems, referred to as "candle sticks". Since the disease is systemic, infected stems and roots show brownish discolouration. During periods of high humidity, bacterial exudation (appears as gum) can readily be observed on the lower leaf surfaces of infected leaves and on the petioles and stems. The disease is favoured by wet conditions. This disease is primarily spread by infected cuttings. It can also be mechanically transmitted by raindrops, use of contaminated farm tools (e.g. knives), chewing insects (e.g. grasshoppers) and movement of man and animals through plantations, especially during or after rain. Yield loss due to the disease may range from 20 to 100% depending on variety, bacterial strain and environmental conditions. What to do:

|

| Brown leaf spot (Cercosporidium henningsii) Symptoms are restricted to older leaves. Brownish round spots with definite borders appear on the upper leaf surface. On the lower leaf surface, they are brownish-grey in colour. Infected leaves later become yellow and eventually drop. In wet areas the disease may cause a yield reduction of up to 20%. What to do:

|

| Cassava brown streak virus disease (Potyvirus - Potyviridae) It is particularly serious in coastal areas of Kenya, Zanzibar, Mozambique and Tanzania and lakeshore region of Malawi and in Uganda and is a threat to the whole of sub-Saharan Africa. The virus is vectored by whiteflies (Bemisia spp.) and also transmitted through infected cuttings. Symptoms include yellowing (leaf chlorosis) and brown streaks in the stem bark (cortex). Infected tubers have brown streaks (root necrosis) (Field Crops Technical Handbook, MoA, Kenya). It's a stealth virus, which destroys everything in the field. The leaves may appear healthy even when the roots have rotted away.

What to do:

|

| Anthracnose (Glomerella manihotis) Initial symptoms of the disease are oval lesions ("sores") on young stems. On older stems, raised fibrous lesions develop that eventually become sunken.

What to do:

|

| Some fungi growth on cassava chips, usually when the moisture content of cassava chips exceeds 14%, making them unfit for feed and food. A survey of cassava chips processing areas of West Africa has indicated that the most common fungi were Rhizopus sp. and Aspergillus sp. (IITA, 1996).

What to do:

For more information on Storage pests click here. |

Contact information

For seeds

- Kenya Seed Company Limited -Varieties: TMS 30572, KME 1, and KME 2. Operates in:Tanzania, Uganda, Rwanda, Burundi, South Sudan, and Malawi. website: www.kenyaseed.com

- Agri Seed Co. Ltd.(Tanzania) - Web page: https://agrifichallengefund.org/agri-seedco/

- NASECO Seed Company Limited(Uganda) –web page: https://www.nasecoseeds.net/about.php

- IITA - International Institute of Tropical Agriculture (Nigeria)- Operate in: Nigeria, Cameroon, Kenya, Tanzania, Uganda, Rwanda, Burundi, and Democratic Republic of Congo. website:www.iita.org,

- NAFASO(Burkina Faso) -Varieties:Rayongo, Kossou, and Supra.Phone Number Contact:Operate in: Mali, Niger, and Togo.Address at 01 BP 4664, Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso contact:+226 25 30 63 45. email: info@nafaso.net.

- Pannar Seed(South Africa) –web page: https://www.pannar.com/

- Farm Inputs Care Centre (FICA) (Uganda)- web page> https://www.crunchbase.com/organization/farm-inputs-care-centre-uganda-fica

For more information on cassava visit:

Farmlink. Web page. http://www.farmlinkkenya.com/cassava-can-be-processed-into-many-products/#:~:text=Cassava%20tuber%20is%20rich%20in,defensive%20system%20to%20work%20properly.

References and information links

References

1. AIC (2002). Field Crops Technical Handbook, Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development, Nairobi, Kenya.

2. Allem, A. C. (2001). The origins and taxonomy of cassava. Cassava: biology, production and utilization, 1-16.

3. De Oliveira, E. C., & Miglioranza, É. (2014). Anatomy of cassava leaves. European Scientific Journal, 2, 167-171.

4. CAB International (2005). Crop Protection Compendium, 2005 edition. Wallingford, UK www.cabi.org

5. Ezulike, T.O., Egwuatu RI. (1993). Effects of intercropping cassava and pigeon pea on green spider mite Mononychellus tanajoa (Bondar) infestations and on yields of the associated crops. Discovery and Innovations, 5:355-359.

6. ICTVdB Management (2006). 00.057.0.71.002. Cassava brown streak virus. In: ICTVdB - The Universal Virus Database, Columbia University, New York, USA. ICTVdB - The Universal Virus Database http://ictvonline.org

7. INPhO. Post-harvest Compendium. Cassava. www.fao.org

8. James, B., Yaninek, J., Neuenschwander, P. Cudjoe, A., Modder, W., Echendu, N. and Toko, M. (2000). Pest control in cassava farms. International Institute of Tropical Agriculture (IITA). ISBN: 978-131-174-6 www.iita.org

9. James, B., Yaninek, J., Tumanteh, A., Maroya, N., Dixon, A.R. and Kwarteng, J. (2000). Starting a cassava farm. International Institute of Tropical Agriculture (IITA). ISBN: 978-131-173-8 See also online under www.iita.org

10. Manihot esculenta Crantz in GBIF Secretariat (2021). GBIF Backbone Taxonomy. Checklist dataset https://doi.org/10.15468/39omei accessed via GBIF.org on 2021-12-15.

11. Msikita, W., James, B., Nnodu, E., Legg, J., Wydra, K. and Ogbe, F. (2000). Disease control in cassava farms. International Institute of Tropical Agriculture (IITA). ISBN: 978-131-176-2 www.iita.org

12. Natural Resources International Ltd (2004). DFID Renewable Resources Research Strategy Annual Reports for 2003-2004 for Crop Post-Harvest, Crop Protection, Forestry Research, Livestock Production and Post-Harvest Fisheries research Programmes. Natural Resources International Limited, Aylesford, Kent, UK. (CD-ROM)

13. Neuenschwander, P. (1998). Impact of two accidentally introduced Encarsia species (Hymenoptera: Aphelinidae) and other biotic and abiotic factors on the spiralling whitefly (Aleurodicus dispersus (Russell) (Homoptera: Aleyrodidae), in Benin, West Africa. Biocontrol Science and Technology. 8, 163-173.

14. Neuenschwander, P. (2003). Biological control of cassava and mango mealybugs. In Biological Control in IPM Systems in Africa. Neuenschwander, P., Borgemeister, C and Langewald. J. (Editors). CABI Publishing in association with the ACP-EU Technical Centre for Agricultural and Rural Cooperation (CTA) and the Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation (SDC). pp. 45-59. ISBN: 0-85199-639-6

15. Nutrition Data www.nutritiondata.com.

16. Plant Protection and Regulatory Services Directorate (PPRSD) (2000). Handbook of crop protection recommendations in Ghana: An IPM approach. Vol. 3: Root and Tuber Crops, Plantains. E. Blay, A. R. Cudjoe and M. Braun (Editors). Published by PPRSD with support of the German Development Cooperation (GTZ). ISBN: 9988-8025-6-0

17. Theberge, R.L. (Ed) (1985). Common African pests and diseases of cassava, yam, sweet potato and cocoyam. International Institute of Tropical Agriculture, IITA Ibadan, Nigeria. ISBN: 978-131-001-4

18. Yaninek, S., Hanna, R. (2003). Cassava green mite in Africa-a Unique Example of Successful Classical Biological Control of a Mite Pest on a Continental Scale. In Biological Control in IPM Systems in Africa. Neuenschwander, P., Borgemeister, C and Langewald. J. (Editors). CABI Publishing in association with the ACP-EU Technical Centre for Agricultural and Rural Cooperation (CTA) and the Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation (SDC). pp. 61-75. ISBN: 0-85199-639-6.

Information links

- https://www.expertmarketresearch.com/reports/cassava-processing-market

- https://www.iita.org/cropsnew/cassava/

- https://www.healthline.com/nutrition/cassava#how-to-prepare

- AIC (2002). Field Crops Technical Handbook, Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development, Nairobi, Kenya.

- Bellotti, A., Smith, L., Lapointe S. (1999). Recent advances in cassava pest management. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 44: 343-70.

- Bohlen, E. (1973). Crop pests in Tanzania and their control. Federal Agency for Economic Cooperation (bfe). Verlag Paul Parey. ISBN: 3-489-64826-

- CAB International (2005). Crop Protection Compendium, 2005 edition. Wallingford, UK www.cabi.org

- Ezulike, T.O., Egwuatu RI. (1993). Effects of intercropping cassava and pigeon pea on green spider mite Mononychellus tanajoa (Bondar) infestations and on yields of the associated crops. Discovery and Innovations, 5:355-359.

- ICTVdB Management (2006). 00.057.0.71.002. Cassava brown streak virus. In: ICTVdB - The Universal Virus Database, Columbia University, New York, USA. ICTVdB - The Universal Virus Database http://ictvonline.org

- INPhO. Post-harvest Compendium. Cassava. www.fao.org

- James, B., Yaninek, J., Neuenschwander, P. Cudjoe, A., Modder, W., Echendu, N. and Toko, M. (2000). Pest control in cassava farms. International Institute of Tropical Agriculture (IITA). ISBN: 978-131-174-6 www.iita.org

- James, B., Yaninek, J., Tumanteh, A., Maroya, N., Dixon, A.R. and Kwarteng, J. (2000). Starting a cassava farm. International Institute of Tropical Agriculture (IITA). ISBN: 978-131-173-8 See also online under www.iita.org

- Msikita, W., James, B., Nnodu, E., Legg, J., Wydra, K. and Ogbe, F. (2000). Disease control in cassava farms. International Institute of Tropical Agriculture (IITA). ISBN: 978-131-176-2 www.iita.org

- Natural Resources International Ltd (2004). DFID Renewable Resources Research Strategy Annual Reports for 2003-2004 for Crop Post-Harvest, Crop Protection, Forestry Research, Livestock Production and Post-Harvest Fisheries research Programmes. Natural Resources International Limited, Aylesford, Kent, UK. (CD-ROM)

- Neuenschwander, P. (1998). Impact of two accidentally introduced Encarsia species (Hymenoptera: Aphelinidae) and other biotic and abiotic factors on the spiralling whitefly (Aleurodicus dispersus (Russell) (Homoptera: Aleyrodidae), in Benin, West Africa. Biocontrol Science and Technology. 8, 163-173.

- Neuenschwander, P. (2003). Biological control of cassava and mango mealybugs. In Biological Control in IPM Systems in Africa. Neuenschwander, P., Borgemeister, C and Langewald. J. (Editors). CABI Publishing in association with the ACP-EU Technical Centre for Agricultural and Rural Cooperation (CTA) and the Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation (SDC). pp. 45-59. ISBN: 0-85199-639-6

- Nicol, C. M. Y., Assadsolimani, D. C. and Langewald, J. (1995). Caelifera: Short-horned grasshoppers and locust. In "The neem tree Azadirachta indica A. Juss. And other meliaceous plants sources of unique natural products for integrated pest management, industry and other purposes". Pp. 233- Edited by H. Schmutterer in collaboration with K. R. S. Ascher, M. B. Isman, M. Jacobson, C. M. Ketkar, W. Kraus, H. Rembolt, and R.C. Saxena. VCH. ISBN: 3-527-30054-6 r ISBN

- Nutrition Data www.nutritiondata.com.

- Olaifa, J. I., Adenuga, A. O. (1988). Neem products for protecting field cassava from grasshopper damage. Insect Science. Appl. Vol. 9, No.2, pp 267-270.

- Plant Protection and Regulatory Services Directorate (PPRSD) (2000). Handbook of crop protection recommendations in Ghana: An IPM approach. Vol. 3: Root and Tuber Crops, Plantains. E. Blay, A. R. Cudjoe and M. Braun (Editors). Published by PPRSD with support of the German Development Cooperation (GTZ). ISBN: 9988-8025-6-0

- Théberge, R.L. (Ed) (1985). Common African pests and diseases of cassava, yam, sweet potato and cocoyam. International Institute of Tropical Agriculture, IITA Ibadan, Nigeria. ISBN: 978-131-001-4

- Yaninek, S., Hanna, R. (2003). Cassava green mite in Africa-a Unique Example of Successful Classical Biological Control of a Mite Pest on a Continental Scale. In Biological Control in IPM Systems in Africa. Neuenschwander, P., Borgemeister, C and Langewald. J. (Editors). CABI Publishing in association with the ACP-EU Technical Centre for Agricultural and Rural Cooperation (CTA) and the Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation (SDC). pp. 61-75. ISBN: 0-85199-639-6

Review Process

Dr. Patrick Maundu, James Kioko, Charei Munene and Monique Hunziker, June 2024