Geographical Distribution in Africa

Geographical Distribution of Leafmining flies in Africa (red marked) Updated 10 July 2019. Source CABI

Leaf mining flies are serious pests of vegetables and ornamental plants worldwide.

General Information on Pest and Damage

Introduction

It is important to differentiate leafmining flies and leafmining caterpillars, since the management of the two groups of pests is different.

(The leafminers attacking coffee, cotton, groundnut, soybean and citrus are caterpillars, not leafmining flies. They are described under their respective crop).

Here we describe the leafmining flies:

Major species of leafmining flies in Africa are:

- The serpentine leaf miner ( Liriomyza trifolii)

- The vegetable leaf miner (L. sativae)

- The cabbage leaf miner (L. brassicae)

- The pea leaf miner (L. huidobrensis)

Leafmining flies are serious pests of vegetables and ornamental plants worldwide. They are occasional pests of brassicas. Liriomyza brassicae is cosmopolitan. In Africa it is reported from Egypt, Ethiopia, Kenya, Mozambique, Zimbabwe, Cape Verde and Senegal. Host plants are primarily crucifers.

Two species of serpentine leafmining fly, L. trifolii and L. sativae, are considered serious pests of tomatoes. Both species are cosmopolitan. Liriomyza sativae is a typical American pest, whereas the typical leafmining fly in Europe is L. bryoniae. Liriomyza trifolii is common on tomato in America and Europe, and L. huidobrensis is occasionally reported on tomato in America but damage has been recorded mainly on ornamentals. Leafmining flies L. trifolii and L. sativae are closely related with similar appearance and overlapping host ranges.

In Africa, L. trifolii has been reported in several countries, including Kenya, Mauritius, Reunion, Senegal, South Africa and Tanzania. In Kenya, Liriomyza trifolii was introduced to Kenya in the late 1970s through chrysanthemum cuttings from Florida (USA). Since then, Liriomyza species have been found throughout the country, attacking vegetables and ornamental plants. Liriomyza. huidobrensis is currently a serious pest of ornamentals and passion fruits. Liriomyza sativae was recently recorded in Kenya.

L. brassicae has also been reported for many years as a pest on brassicas and legumes, but in general, the damage done to mature crops is largely superficial.

Damage

Female leafmining flies puncture leaves and in some instances also fruits/pods (e.g. peas) with their ovipositor to feed and to lay eggs. These punctures can serve as entry point for disease-causing bacteria and fungi, but in most cases they are not of economic importance. However, they can be a problem for export products such as on snow-peas and ornamentals. Eggs are laid inside the plant tissue, and they cannot be removed through washing; this may lead to rejection of the produce when their presence is detected during import inspection.

|

| Leaf of okra seedling showing attack by leaf mining flies. Note pupa (yellow colour) on leaf. |

|

© A.M.Varela, icipe

|

Damage by maggots feeding in the plant tissue is economically more important than the feeding punctures of adult flies. Maggots feed between the upper and lower surface of the leaf making tunnels or mines as they move along. Although individual mines on leaves do not produce much damage, heavy attacks, especially on seedlings, may result in dying off of young plants. Heavy attack leads to large-scalenecrosis of leaf tissue, eventual shrivelling of the whole leaf and may result in complete defoliation of crops. Defoliation of tomato plants may also expose fruits to sunburn and thus affect their market value.

|

| Leafmining flies damage on tomato leaf. Note maggot ready to pupate (yellow) and pupa (brown). |

|

© A. M. Varela, icipe

|

Heavy infestation reduces the photosynthetic capacity of the plant and affects the development of flowers and fruits. However, mature plants of most crops such as tomato and cabbage can withstand considerable leaf mining, especially on the lower or outer leaves. In other crops, where feeding occurs on the marketable part of the crop, even slight damage may lead to rejection of the crop. This is particularly important for export crops, as most Liriomyza species are considered quarantine pests in the EU and there have been rejections of produce exported to Europe.

Host range

Leaf miners are able to colonise a wide range of plants (primarily although not exclusively Solanaceae, Leguminosae and Asteraceae). Liriomyza flies have become important pests of horticultural crops and potatoes in the tropics and subtropics. The most common species, L. sativae, L. trifolii and L. huidobrensis, feed on a wide range of plants. Main host plants include cabbage and other brassicas (cruciferous crops), okra, onion, pigeon pea, bell pepper, cucumber, pumpkin, cowpea, potato, passion fruit, tomato and common bean.

In East Africa, these leaf mining flies are recorded from most export vegetables with sometimes extremely heavy damage on French and runner beans, citrus okra, eggplant, passion fruit and peas. Severe infestations have also been recorded on cut flowers. Liriomyza brassica attacks mainly crucifers. It has no economic importance in the region.

Affected plant stages

Seedling and vegetative growing, flowering and fruiting stages.

Affected plant parts

Leaves and pods.

Symptoms by affected plant part

Feeding and egg-laying by female flies result in white puncture marks on leaves. These punctures are easily seen and are the first signs of attack.

Feeding by maggots leaves irregular mines on the leaves, with occasional thread-like black frass inside the mine. Severely mined leaves may turn yellow, disfigured, and drop.

Biology and Ecology of Leafmining Flies

Eggs are very tiny (about 1.0 mm long and 0.2 mm wide), greyish or yellowish white and slightly translucent. They are laid inside the leaf tissue, just below the leaf surface. In some instances eggs are laid below the epidermis of fruits/pods (e.g. peas). Eggs hatch in about 3 days.

Larvae are small yellow maggots (about 2 to 3 mm long when fully-grown). They are found feeding inside the leaf tissue, leaving a long, slender, winding, white tunnels (mines) through the leaf. They pass through 3 larval stages. After 5 to 7 days the maggots leave the mines and pupate either on the leaf surface or - more commonly - in the soil. In some cases, maggots pupate within the mines.

The pupae are very small, about 2 mm long and 0.5 mm wide) oval, slightly flattened ventrally with variable colour varying from pale yellow-orange to golden-brown. They have a pair of cone-like appendages at the posterior end of the body. Adults emerge 4 to 5 days after pupation.

Leafmining adult flies are small, about 2 mm long. They are greyish to black with yellow markings. Female flies are slightly larger than males.

|

| Legless maggot of the leafmining fly (Liriomyza brassica) with no separate head capsule, transparent when newly hatched but colouring up to a yellow orange in later instars, up to 3 to 4 mm long. |

|

© Jerry A. Payne, USDA Agricultural Research Service, www.bugwood.org

|

|

| Leafminer (Liriomyza sativae) pupa within tunnel of onion. They are oval, slightly flattened and about 1 - 2 mm long. |

|

© Whitney Cranshaw, Colorado State University, Insect Images (www.insectimages.org)

|

|

| Leafmining fly on okra leaf |

|

© A.M.Varela, icipe

|

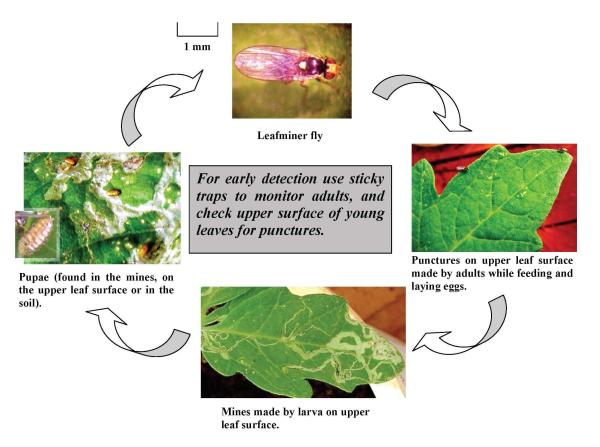

Life cycle

The life cycle varies with host and temperature. The average life cycle is approximately 21 days in warm conditions, but can be as short as 15 days. Thus, populations can increase rapidly.

|

| Leafminer life cycle |

|

© A. M. Varela, icipe

|

Pest and Disease Management

Pest and disease management: General illustration of the concept of Infonet-biovision

This illustration shows the methods promoted on infonet-biovision. The methods shown at the top have a long-term effect, while methods shown at the bottom have a short-term effect. In organic farming systems, methods with a long-term effect are the basis of crop production and should be preferred. On the other hand methods with a short-term effect should be used in emergencies only. On infonet we do not promote synthetic pesticides.

Further below you find concrete preventive and curative methods against Leaf miners.

Cultural practices

Monitoring and inspection methods

Small black and yellow flies may be detected flying closely around the crop or on the leaves. Inspection of the leaf surface will reveal punctures of the epidermis and the greenish-white mines in the leaves. Feeding maggots will be found at the end of the mine. When the maggots have already left the mine to pupate, the mine will end with a small convex slit in the epidermis. Occasionally the pupae may be found on the leaf surface, although in most cases they pupate in the soil.

A monitoring technique for leaf miners used in fresh market tomatoes in USA is to place plastic trays beneath plants at several randomly chosen places in the field. Mature larvae that drop from foliage accumulate on the trays and pupate there, providing a measure of leaf miner activity. Visual rating systems to assess the total number of leaf miners on tomato have also been developed. The flies can also be monitored by using yellow sticky traps.

It is also important to monitor the presence and activity of natural enemies. Absence of pupae on leaves or in trays placed beneath plants, even if new mines are present, is an indication that natural enemies are keeping leafminers controlled.

The economic importance of damage by Liriomyza leafminers depends on the plant stage and on the crop. These factors must be considered when determining whether to implement control. Young plants can withstand less damage than older ones. On leafy crops such as spinach, lettuce, and chard, a 5% threshold level is often used. Much more damage can be tolerated in crops where the leafminers affect the leafy, non-marketable parts of the plant than in crops where the marketable part is attacked, particularly in high value crops such as snow peas, cut-flowers and ornamentals.

Leafminers can also be monitored by foliage examination for the presence of mines and larvae and by trapping adult flies with yellow sticky traps. Yellow sticky traps used for mass trapping can effectively control the pest at low densities. Visual rating systems to assess the total number of leafminers on tomato have been developed in the USA.

Cultural control

Normal agricultural hygiene can play an important part in controlling leaf miner damage:

- Hand-picking and destroying of mined leaves.

- Destroying all infested leaves and other plant material after harvest.

- Destroying pupae before planting a new crop: ploughing and hoeing can help reduce leaf mining flies but exposing pupae, which then would be killed by predators or by desiccation. Flooding the soil followed by hoeing could kill or release much of the buried pupae.

- Where new stock is obtained as seedlings rather than seed, check carefully and destroy infested plants before planting to prevent introduction of pests including leaf miners.

- Solarisation can kill pupa in the soil. For more information on solarisation click here

Biological pest control

Natural enemies

Leaf mining flies have a wide range of natural enemies, mainly parasitic wasps, which normally keep them under control. However, the indiscriminate use of broadspectrum pesticides disrupts the natural control resulting in major leafminer outbreaks.

The three major species present (L. sativae, L. trifolii and L. huidobrensis) in Kenya have been accidentally introduced. Local parasitic wasps now attack these leafmining flies, but they only afford satisfactory control when they are present early in the crop cycle.

One of the most efficient parasitic wasps for control of leaf mining flies, Diglyphus isaea, is now present in Kenya, and it is giving satisfactory control on some crops. However, this parasitic wasp often comes too late to prevent early damage and farmers resort to pesticides too early, thus preventing population build-up of this natural enemy affecting its efficiency. This parasitic wasp is now being reared locally and is commercially available in Kenya, but smallholder growers have no access to the parasitic wasps. Therefore it is important to conserve this and other naturally occurring natural enemies.

|

|

| Parasitic wasp Diglyphus isaea |

|

© A.M.Varela, M.Billah, icipe

|

For more information on natural enemies click here.

Biopesticides and physical methods

Neem

Neem-based pesticides are used for control of leaf mining flies. Neem products reduce fecundity and longevity of flies and disrupt the development of the maggots. They can be applied as drench or as foliar sprays.

Weekly applications of aqueous neem seed extracts (ANSE) at 60 g/l and neem oil (2.5 to 3%) reduced leaf miner damage on tomato (Ostermann and Dreyer, 1995).

Weekly foliar sprays with a commercial neem product (Neemros®) at rates of 25 and 50 g/l water and a spray volume of about 900 l/ha controlled leaf mining flies on experimental tomato fields in Kenya. Five applications were done starting 20 days after transplanting. Emergence of leaf mining flies decreased with increased dosage (icipe).

In Kenya, the integration of neem products in the management of leaf mining flies in high value crops (e.g. snow peas, French beans and cut flowers) resulted in the increase of the beneficial wasp Diglyphus isaea, a considerable reduction of pesticide use, and of reduced rejection of the produce due to leaf miner damage (icipe).

For more information on Neem click here

Spinosad

Spinosad, a bacterium derivative, used mainly for control of caterpillars, thrips, and fruit flies, controls Liriomyza leafminers as well. Spinosad does not significantly affect beneficial organisms including ladybugs, green lacewings, minute pirate bugs, and predatory mites. Its use is now accepted in organic production. It is commercially available in Kenya (e.g. Tracer®).

Traps

Yellow sticky traps used for mass trapping and monitoring and can effectively control the pest at low densities.

For further information on sticky traps click here.

Information Source Links

- Varela, A.M., Seif, A. and Loehr, B. (2003). A Guide to IPM in Tomato Production in Eastern and Southern Africa. ICIPE. www.icipe.org. ISBN 92 9064 149 5.

- CABI. (2004). Crop Protection Compendium, 2004 Edition. © CAB International Publishing. Wallingford, UK. www.cabi.org

- Ostermann, H. and Dreyer, M. (1995). Vegetables and grain legumes. In The Neem Tree- Source of Unique Natural Products for Integrated Pest Management, Medicine, Industry and Other Purposes. H. Schmutterer (ed.). pp 392-403.ISBN: 3-527-30054-6.